Friends And Heroes

10. Kamala Harris

California Attorney General Kamala Harris is one of the rising stars of the Democratic Party and has been mentioned for any number of important posts from Governor of California to serving on the Supreme Court. After easily winning re-election for her current post, she announced she was running for Senator.

Politics is a dirty game, and the current logjam in Congress makes it even more unattractive. That’s why I’m so glad she’s willing to take on our daunting government and make it work. Let’s support her campaign to the upmost!

9. Daryl “Chill” Mitchell

I met Darryl when he was in the hip hop group Groove B. Chill. All great guys. They were funny, they could dance, and they were disciplined and hard working. There were a little ahead of their time, but Chill took his stand out performance in House Party and built a great acting career for himself.

Chill’s motorcycle slid on a clear and put him in a wheelchair. But his spirit is still the same. Every time I see Chill he makes me feel better about myself. Now he’s in New Orleans working with friends on the new CSI Series and of course everyone loves him. What a great man!

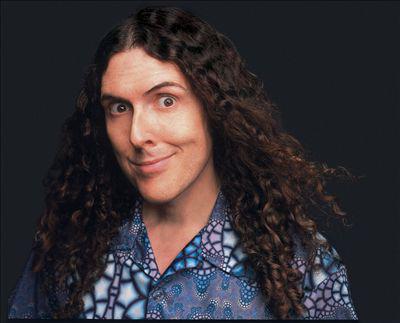

8. Weird Al Yankovic

I grew up on Mad Magazine, so I’ve always admired the career of Weird Al Yankovic. He was always funny without having to get crude, and later I found out he wrote and produced his own material, and directed his own parody videos. It’s hard for any musical artist to maintain a career that long, let alone a guy working in such a specific niche as musical parody.

But Weird Al just had his best year ever, using the internet to help pay for a dazzling array of videos for his new album, and getting kudos from the Wall Street Journal for his business acumen. He’s also the nicest guy with a loving, wonderful family. He knows how to live. He’s a hero to me.

7. Dr. Chris Hudlin

I love my family, but Dr. Chris Hudlin is one of my favorites. He’s close to my age, he’s always been a cool guy, and he’s a great doctor who loves his family. His personality is so much like his dad, Irving Hudlin, who was an amazing man who fought in three wars and always had the best smile. When our aunt, my dad and his dad passed away in quick succession, we were part of the “next generation” that stepped into those huge shoes to hold the family together.

6. Van Jones

I met Van in a happy accident. We made separate appearances on Roland Martin’s show years ago and both got in the same limo heading home. We decided to share and talk politics and popular culture the whole way home.

Van does 21st social justice advocacy, from environmental justice to his great new movements, #yeswecode, which could dramatically improve employment among black folks and change the way we think as a people.

As a correspondent for CANN, he was the voice of reason covering Ferguson, including delivering a much needed challenge to Don Lemon (see below):

5. Richard Hudlin

Businessmen, educators, soldiers…all my aunts and uncles are incredible. Now my Uncle Richard is the last redwood standing in the forest. He’s a card carrying Mensa member who at 80 can do more jumping jacks than a gaggle of little kids at Thanksgiving.

My kids have heard me talk about the influence of my very unconventioaal thinking uncle their whole young lives. They finally got to meet the man who introduced me to seaweed, chess, and other not very East St. Louisian experiences.

4. Alexis Templeton

My kids had never been to my hometown of East. St. Louis. So when my cousin Chris decided to go visit his mom, I brought my family back to meet all their cousins and show them where I grew up.

While visiting my cousin Tony’s house (that’s where my daughter and my uncle Richard were talking on the floor, above) he told me his niece is one of the organizers of the Ferguson protests and showed me a profile on her and her partner on Al Jeezera.

I was so happy to see young people involved in social protest, and even happier that she was so thoughtful and well informed about what she was doing.

Me flanked by cousins Brittany Hudlin and Alexis Templeton.

The next day at Thanksgiving we talked for a while about how her organization was going to turn their momentum into political power. They were several steps ahead of me. Man, she’s awesome!

3. Marcus Miller & Craig Robinson

I’ve worked with Marcus Miller for decades now, starting with him scoring my first film HOUSE PARTY. Marcus has done it all, from producing every important Luther Vandross album, to producing Miles Davis’ last great works. He produced Da Butt for EU and is that funky ass bass player on Funkin’ For Jamaica record.

He’s also a fantastic ambassador for jazz: articulate, funny, humble and with lifetimes of stories and experiences. It had been too long since we worked together but he was my first call for the Black Movie Soundtrack show at the Hollywood Bowl.

Marcus assembled an all star band with a mix of legends like Wah Wah Watson and Paul Jackson Jr and new jacks with insane chops. He took my input and balanced that with the meager budget and the needs of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and made something beautiful. Which is what he does…make beautiful things.

I’ve been a fan of Craig Robinson for years, but I’ve never had a chance to work with him. But when I ran into him at a backyard party and I mentioned the upcoming concert at the Bowl, his eyes rolled in the back of his head when I mentioned Marcus Miller. The fact that he’s a dope enough musician to have that reaction was the clear sign he was the man to host the event.

A week later I was in rehearsal and it was feeling so good I texted him and told him to come over. He got caught up like I was and he started clowning with me and the band. This became the skeleton of what the show would be.

On show day, the two of us sat down with a well-researched but very academic document giving the history of black film and the music. We chopped it down and added jokes. In two hours, we had a script.

A few hours after that, it was performed live in front of 11,000 people. Craig KILLED.

The man is brilliant.

2. Stephen Bochco

Everyone who is paying attention knows that Stephen Bochco is one of the greatest producers in the history of television. From Hill Street Blues to LA Law to Doogie Houser MD to NYPD Blues to his new show MURDER IN THE FIRST, he has redefined and expanded the medium over and over again.

Steven has been a friend and mentor to me since I first introduced myself to him at a party and asked him why black dramas weren’t succeeding on television. Which let to him recruiting me to work on CITY OF ANGELS, a black medical series with Blair Underwood, Vivica Fox, Hill Harper, Maya Rudolph (in a dramatic role), Viola Davis, Tamara Taylor and a young actress named Gabrielle Union. Stephen has launched so many careers of talented black people both in front and behind the camera it’s ridiculous.

We’ve had countless dinners where he advises me on work and life, most famously chastising me for not asking my girlfriend to marry me. I took his advice, and two kids later, he was very right.

The lessons continue. This year he has taught me so much about how to overcome adversity with courage, strength, humor and honesty that I can’t imagine life without him. He is a true hero.

1. Jonathan Hicks – For A Lifetime Of Excellence

Rather than me trying to capture the complex wonderfulness of Jonathan, I’m going to use the obit from the Kappa Journal:

By Jesse Washington

Jonathan P. Hicks, who touched thousands of lives around the globe as one of Kappa Alpha Psi’s most remarkable Brothers, has joined the Chapter Invisible. Hicks died of pancreatic cancer at his home in Brooklyn on November 3, 2014. He was 58 years old.

Hicks was also a journalist, singer, philanthropist, world traveler, gourmet cook, husband, father, and Christian. Most of his professional career was spent at The New York Times, where over 24 years he wrote numerous front-page articles on business and politics. After leaving the Times, Hicks wrote a column for The New York Amsterdam News and was a senior national correspondent for BET.com, the website of Black Entertainment Television.

He was co-editor of two books of essays, hosted a radio show that explored issues affecting disadvantaged communities, and wrote the script for a successful documentary. He lectured at numerous colleges and universities in England, America and Liberia. Hicks served two stints as editor of the Kappa Alpha Psi Journal, helped raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for Kappa college scholarships, was a recipient of the Elder Watson Diggs Award, and shared his vocal talents in various recordings and countless venues.

Yet despite this illustrious resume, Jonathan Hicks was not defined by his accomplishments. Rather, his achievements were the gateways to Hicks’ true passion: relationships.

Hicks was a man who loved people. He gave unconditionally and generously of his time, musical gifts, journalistic expertise, humor, and connection to God. He gave in extraordinarily deep and lasting ways to the commitment and fidelity of Kappa brotherhood. Always, Hicks gave for the sake of giving, as an expression of love for humanity.

He ended many of his phone conversations with three words: “I love you.”

“He was a treasure,” says Brother Samuel C. Hamilton, Grand Polemarch from 2003 to 2007.“In singing or in print, or just in conversation, he had a way about him, a very effective way of spreading the tenets of the fraternity and making them come alive for those who may not have had the same vision he had,” Hamilton says.

“You don’t replace someone like that,” Hamilton continued. “You can feel that a void exists, because you just can’t replace him in that way, in that package.”

“It may sound blasphemous,” says Brother Ivann Greene, a longtime friend who was polemarch of Delta Omega chapter at the University of Missouri when Hicks was initiated in 1977, “but Jonathan was on par in terms of respect with one of our founders.”

Greene recalled the way Hicks made it a point to know every line that came through Delta Omega, and how he traveled the country and the world reaching out to Brothers.

“He was the glue,” Greene says. “And he continues to be, because he helped us all understand that our mission is to mentor one another.”

Jonathan Pruitt Hicks was born December 4, 1955, in St. Louis, Missouri. His father, John H. Hicks, had been initiated into Kappa Alpha Psi at Beta Chapter, University of Illinois, in 1947, and was the first black reporter at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. His mother, Minnie, had a degree in chemistry and worked at the National Institutes of Health.

Jonathan grew up in a musical home with one sister and four brothers, and began singing as a child. His father moved from reporting to a diplomatic career with the United States Information Agency, and the family lived in Liberia and Berlin— Jonathan spoke German throughout his life—before settling in Washington, D.C.

As a teen, Jonathan sang with the D.C. Youth Chorale and the Washington D.C. Choral Arts Society. He met his future wife, Christy DuBose Hicks, while singing in the choir at Woodrow Wilson High School, where he also was a member of the key club, student council vice president, manager of the basketball team, a reporter for the school newspaper, and an editor of the yearbook.

“I figured I would either be a journalist or an opera singer,” Hicks said in a recent interview.

After graduating from high school, Hicks enrolled at the University of Missouri, where he quickly made himself familiar to the approximately thirty Brothers on the yard at Delta Omega chapter.

“We noticed him at all of our events and were like, who is this guy?” recalls Greene, who was the polemarch. “He was at every doggone Kappa event, which was really shocking, because no one knew him.”

“He was kind of mysterious,” recalls Brother Junius Fisher, who was a Delta Omega neophyte at the time. “He was this quiet guy who would come and talk to the brothers one on one. He wasn’t hanging out at parties and all that stuff, but would pull you aside and talk and develop a relationship with you like that.”

Hicks became a pledge in late 1976 with four other prospective members. The process was old school and very demanding. Brothers from out of town arrived at Mizzou’s campus every weekend to participate. A few weeks in, all four of the other pledges dropped out.

“Once everyone was gone, we had no idea Jonathan would stay. Who does that?” Fisher says. “He showed up the next day, still got his red sweatshirt on. We were like, what’s up with you? You know everybody quit yesterday?”

“He said, I’m still on line, big brother sir.”

“We were flabbergasted. You’re gonna pledge by yourself? I didn’t think he would make it. I didn’t think anybody could possibly be mentally strong enough to go through an entire pledge period by themselves. The Brothers didn’t ease up, they were probably harder on him. When you have line brothers, you help each other do all the things you have to do. But everything this man had to do did, that this kid did, was magnified ten times. It was truly phenomenal.”

On January 3, 1977, Jonathan was initiated into the fraternity, alone. He made an immediate impact: helping to organize activities and pan-Hellenic conferences, participating in step shows with the long, staff-like canes that were popular at the time, and exhibiting a quiet leadership.

Greene recalls a time when as an undergrad, he was invited into a meeting at a Middle Western Province council gathering. All of the highest provincial officials were there. They informed Greene that they wanted him to fill the junior vice polemarch position. Then Greene saw Hicks, sitting silently in the corner of the room, and realized why he was the one chosen.

“He was such a different Brother, just different from everyone else,” Fisher says. “He had a reach, he just had a desire to just reach out beyond what we saw. We would see the chapter, he would see the district or the national. He would just see the bigger picture.”

After graduation, Hicks’ first full-time journalism job was at the Arizona Daily Star in Tucson, where he had previously been an announcer at a National Public Radio station. He then became a business reporter for the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

His impact in Cleveland lasted far beyond his departure. After Hicks’ death, Phillip Morris, a Plain dealer columnist, wrote about how Hicks always ended their phone conversations with “I love you.”

“It felt good to be loved by Jonathan because he understood the fine art of true and caring friendship. He effortlessly defined the meaning of friendship both in his words and his deeds,” Morris wrote.

Hicks joined The New York Times in 1985, where his coverage included the mayoral campaigns of David Dinkins, Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg; the Senate campaign of Hilary Clinton; an increase in black professionals leaving corporate jobs; the tire and steel industries; city council; congressional races; and the political impact of New York’s demographic shifts.

While at the Times, Hicks received the newspaper’s Publishers Award. Other honors included the public service writing award from the New York Association of Black Journalists, and awards for excellence from the New York Chapter of the National Black MBA Association and from the Arizona Press Association.

From 1985 to 1989, Hicks was editor of the Kappa Journal, which became one of his most passionate projects. One of his proudest moments was assembling the edition commemorating the 75th anniversary of the fraternity. In 2011, he was appointed for a second stint at the helm, which he continued with great pleasure until his death.

Being editor of the Journal allowed Hicks to spread his gospel of fellowship and brotherhood even further. Fisher recalls Hicks’ ability to bring brothers together with his mere presence.

“When he would come and visit anywhere, all you had to do was put the word out and brothers would show up. Seventy brothers would show up, and he didn’t even have to call. They just knew he was there,” Fisher said. “He had this unique ability to bring people together. His vision was different that everyone else’s. Ours was more myopic. His vision was just grand. There were so many different ways he could touch people.”

“But the way he really touched people,” Fisher says, “was through his music.”

The music. The voice. The songs.

Hicks did not sing for the spotlight. He sang for the pleasure of others. He considered his voice a gift that must be shared. Many know him from the Kappa Klassics album, which he recorded with the late Brother Anthony Patrick. In 2010, Hicks assembled MANIFEST, an all-male choral group whose mission is to deliver Christ’s message outside of traditional church settings. Much of the group had sung together in Men Voicing Praise (MVP), a Hicks-led ensemble at Emmanual Baptist Church in Brooklyn.

MANIFEST debuted on February 4, 2011 at the Triad Theater in New York City. Hicks wrote and arranged many songs for the group, whose first album debuted at No. 32 on the Billboard Gospel chart. He also was featured on CDs such as Total Praise Live and Johnny Mercier: A Melodious Christmas. Many other performances were private: He loved to sing for the amusement, through his choice of songs, of his friends. He made people laugh with his melodic commentaries almost as much as with his deadpan jokes.

And of course, there were the weddings.

Hicks sang at literally hundreds of weddings. Mostly for Kappas, but for many other friends as well. Hicks would only sing at the weddings of his friends—never for hire. All he asked for in return was a home-cooked meal and fellowship.

“I don’t think any Kappa member is legally wed unless Jonathan sings at the ceremony. That is a law, right?” jokes the filmmaker Reginald Hudlin.

After being introduced by a mutual friend, Hudlin and Hicks bonded over their shared East St. Louis roots. That led to Hicks being cast as the butler in the Eddie Murphy romantic comedy Boomerang.

“Jonathan is not only a brilliant guy, but he has a dry comic delivery that makes any story he tells twice as hilarious as the next person,” says Hudlin. “So when the actor we cast couldn’t make it, I knew the right person to go to. I called Jonathan, who was working for The New York Times, and asked him to play hooky from work and do a scene with Eartha Kitt and Eddie Murphy. There was no audition, no preparation, we just threw him in the deep end of the pool. And as I predicted, he killed it! It’s one of the funniest scenes in the movie.”

The part fit Hicks perfectly, given his ability to make friends laugh with just a wordless glance or quizzical facial expression.

“Jonathan had a complete comedy skill set,” Hudlin says. “One of my favorite stories of his was about him going to school in the ‘hood’ after a childhood in American schools in Germany. The first time he heard someone ‘axe’ for a pencil, he kept asking, ‘Pardon me, what did you say again?’ There is no way to deliver it the way Jonathan did—the way he can perfectly shift between authentic ‘hood’ tone and texture and his standard American English speaking self. His voices and expressions were as funny as any comic I know, and I know the best.”

Another of Hicks’ talents was his ability to ask Brothers for help. When Hicks asked for assistance—with an event, a committee, a donation—people said yes. They knew Hicks was a giver. Through Hicks, they too could give.

In 1988, Hicks founded the Scholarship Luncheon of the New York Alumni Chapter Foundation of Kappa Alpha Psi. Later named after the late Reginald F. Lewis, the first black billionaire, the foundation has awarded more than $300,000 in college scholarships to top New York City students. A few years ago, he began the foundation’s Annual Prayer Breakfast, which drew prominent pastors from across the country.

Brother LeRoy Barr, a past polemarch of New York Alumni Chapter who was extremely close with Hicks, recalls the boldface names that Hicks gathered at the scholarship luncheon: Percy Sutton, Arthur Ashe, Reginald Lewis, Basil Peterson, The Rev. Calvin Butts, Adrian Fenty, and more.

And still, “Jonathan was the most unassuming, humble nupe there was,” Barr says.

In 2006, when Barr was considering whether to run for polemarch, he sought Hicks’ advice. “He told me that being a polemarch is really a spiritual walk,” Barr recalls. “I began to take that walk, I saw that you have all these Brothers doing exceedingly well in their own lives, but how do we bring them to the table to do this work in tandem under one tent? It’s less about me and more about them. When people talk about the rebirth of New York Alumni chapter, the direction really came from Jonathan, in terms of how to handle people. It had to be a spiritual walk. It had to be less about you and more about the group. That’s what he was all about.”

In 2009, Hicks was awarded a Ford Foundation grant to travel to Liberia to write articles and produce broadcasts about the emergence of the country from a long civil war. He returned to Liberia to coordinate “Preparing for 2011: A Symposium on Political and Election Reporting,” which gathered journalists for two weeks to discuss and analyze the upcoming presidential election. These experiences led Hicks and his wife, Christy, to launch the J. P. Hicks Family Mass Communications Scholarship, which provides tuition, fees, and books for aspiring journalists to attend the University of Liberia.

Hicks left the Times in 2009 and became a senior research fellow at the DuBois Bunche Center for Public Policy at Medgar Evers College. He was host of the weekly radio program Urban Focus, and co-editor of the book From Disaster to Diversity: What’s Next For New York City’s Economy, a collection of essays by prominent New Yorkers. He also was editing the book Black, Brown and Green: Ensuring A Role for People of Color In the Nation’s Green Economy, to be published by the DuBois Bunche Center. And he wrote the script for Back Door Channels: The Price of Peace, a documentary about the historic Camp David meeting between Egypt, Israel and the United States, which was selected for the 2009 Monte Carlo Television Festival.

Over the years, Hicks’ travels took him to South Africa, Liberia, Nigeria, Ghana, Korea, Mexico, Canada, Israel, Qatar, the Philippines, and many European countries. Invariably, he found members of Kappa everywhere he went.

“I’ve met some outstanding and phenomenal Brothers,” says Fisher, “but I don’t think there’s another Brother in the fraternity that has the reach that Jonathan Hicks had. And that’s not downplaying anything anyone else has accomplished. But I guarantee you, there is not one Brother alive today, and maybe not in the history of the fraternity—and I’m not shorting our Founders—who have touched as many Brothers than this man did in his lifetime, worldwide.”

In 2011, Hicks was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Doctors told him he had six months to live. Yet this did not dim his energy or passion for life—it increased it.

“I believe very strongly that this cancer is a ministry,” Hicks said in an interview for this piece in January of 2014—more than two years after he was told to prepare for an imminent death. “So many opportunities have flown my way since my diagnosis. If we are tethered properly to Him, we can get through whatever we have to get through. Right now, this is at the core of everything I deal with.”

There was a lot for Hicks to get through, especially the grueling chemotherapy. But he still wrote for two publications, raised prodigious sums of money for college students, edited the Kappa Journal with joy and vigor, and continued to travel across America and the world. He visited five countries in 2014 alone, before spending his final weeks at home with his family.

Barr, of New York Alumni chapter, was by Hicks’ side after his diagnosis and helped with his every need in the last stages of his life. One day, driving Hicks to chemotherapy, Hicks told Barr that he wanted him to speak at his funeral.

Caught off guard, Barr didn’t know how to respond. He asked Hicks what he wanted people to know.

“Hicks says to me, my treasure is in my relationships,” Barr recalls. “And it’s crystallizing for me as he explains it. Everyone who knew Jonathan felt like they had a personal relationship with him. It doesn’t matter who you were, what station in life, kappa or not, politicans, or just an average person working a day to day job. Everyone who came in contact with him felt like they had a personal relationship with him. He treated those interactions like his treasure.”

Hicks is survived by his wife, Christy DeBoe Hicks; his daughter, Lindsay; his parents, John and Minnie Hicks; his sister, Louise Wilson; his brothers Geoffrey Hicks and Michael Hicks; and numerous beloved uncles, aunts, cousins, nieces, nephews, and sisters- and brothers-in law. Hicks was preceded in death by his brothers Francis Hicks and John Hicks.

“I try to advertise the fact that just because I have cancer, God still blessed me with the ability to do things. So I can set an example, that He can help people,” Hicks said.

“If we tether ourselves to Him, we can do all sorts of things.”