‘Boyz n the Hood’ at 25: A look back at 1991’s black film renaissance

Director John Singleton was a brash young film student at the University of Southern California in the late 1980s when he saw an advance screening of “Colors,” a drama that purported to give viewers a real glimpse of street life in his native South Central Los Angeles. At the post-screening Q&A with a producer, Singleton gave the film’s producer a piece of his mind.

“You advertise this movie like it’s about my community, and it’s really about two white cops,” he recalled saying. “It’s not about what’s really going on there.”

Singleton added that it was obvious that no black people had worked on the movie. When the producer countered with, “Well, Ice-T wrote the music,” he shot back: “Ice-T didn’t write the [expletive] script!”

Singleton eventually made his own movie, “Boyz N the Hood,” a searing coming-of-age story set in a neighborhood overrun with gangs, drugs and automatic weapons. Originally released 25 years ago, on July 12, 1991, “Boyz N the Hood” received a 20-minute standing ovation at the Cannes Film Festival and eventually yielded $58 million at the box office. In addition to making Singleton, who earned a pair of Oscar nominations, one of the hottest writer-directors in Hollywood, it also helped usher in the black film renaissance that flourished in Hollywood during the 1990s.

In 1991, at least 17 black-helmed films opened in theaters, more than in the entire previous decade. Many introduced new black directors, such as Mario Van Peebles (“New Jack City”), Wendell B. Harris Jr. (“Chameleon Street”) and Matty Rich (“Straight Out of Brooklyn”). Granted creative control, these directors made personal movies that invigorated the black audience, who accounted for 25 percent of all ticket sales at the time but were famished for stories with multidimensional characters. They made stars out of Wesley Snipes, Halle Berry, Ice Cube, Angela Bassett and Chris Rock. And their films exploded stereotypes and explored vexing topics such as black-on-black violence, economic exploitation and the crack epidemic.

Even today, the renaissance directors continue to be a reference point. Singleton’s success helped forge the way for F. Gary Gray to make last year’s “Straight Outta Compton,” now the highest-grossing music biopic in history. And the lyrics and imagery of Beyoncé’s visual album “Lemonade” evoke “Daughters of the Dust,” Julie Dash’s mesmerizing 1991 portrait of Gullah women on the Georgia Sea Islands that will be re-released this fall.

Going to the movies in the ’70s was an empowering feeling for black audiences, who finally got to see themselves as the hero-slash-heroine of their own story. But in the ’90s it was more of an enlightening experience — with better production value. Instead of “Coffy,” “Black Caesar” and other sexy action yarns in which blacks stuck it to the Man, the renaissance films offered a realistic, inside view of contemporary black life.

The seeds of the renaissance were planted in 1986, with Spike Lee’s first major feature, “She’s Gotta Have It.” Producer Stephanie Allain, one of the few black studio executives in the ’90s, said Lee’s guerilla filmmaking and outspokenness on social issues was a major influence, when the only other blacks who seemed to be making movies were Eddie Murphy and Prince. “Back then, the notion of a black artist who’s not afraid to speak his mind or put his feelings and point of view into his art was new,” Allain said. “For our generation, that was, like, wow.”

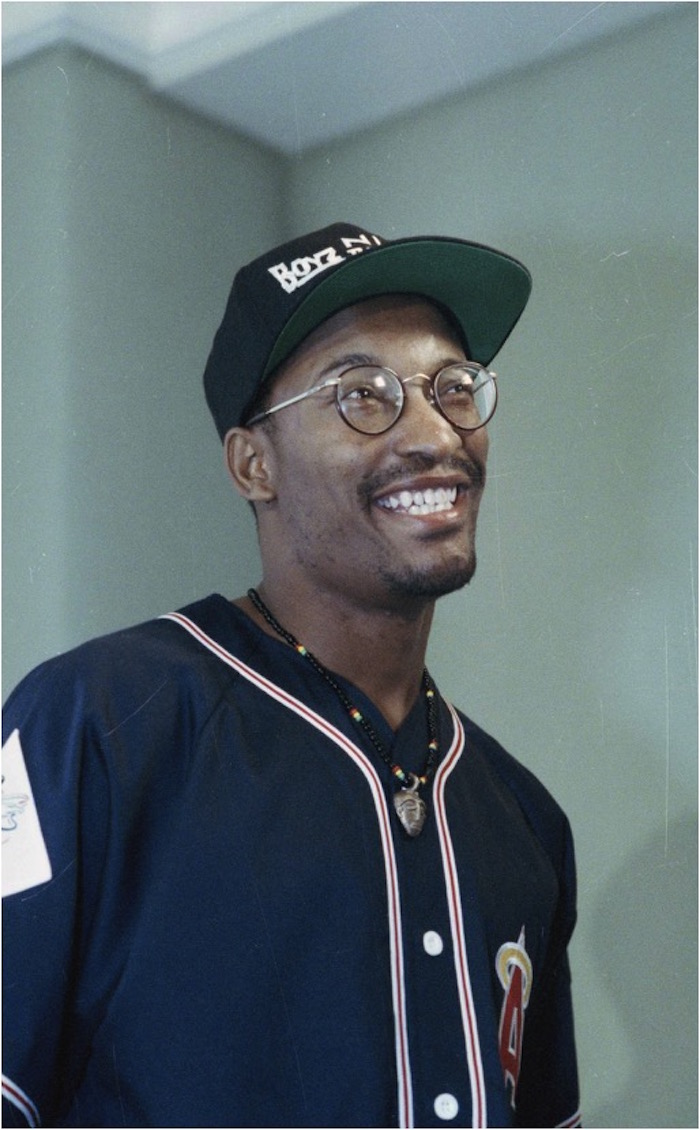

Christopher Reid and Christopher Martin in “House Party 2” from 1991. (©New Line Cinema/Courtesy Everett Collection)

Reginald Hudlin’s “House Party” also helped change perceptions of black directors. The 1990 black teen comedy was made for $2.5 million and took in more than 10 times that amount. “Often, when we talk about revolutionary cinema, we think about something like ‘Battle of Algiers,’ movies that make explicit political statements,” said Hudlin, whose next project was “Boomerang,” an upscale rom-com starring Murphy. “But what I learned with ‘House Party,’ and even more with ‘Boomerang,’ was that showing normal black life on screen is the most revolutionary thing of all.”

TV shows such as “21 Jump Street” and “New York Undercover” had “exposed the larger population to black culture,” Snipes said. At the same time, studios had begun to recognize the value of aiming films at black audiences. Directors tapped into the renewed black pride, with young men and women sporting leather medallions cut in the shape of Africa and T-shirts emblazoned with pro-black slogans (some of which, no doubt, were purchased at Spike’s Joint, the filmmaker’s hip retail shop in downtown Brooklyn). They also drew on the growing rage over the rising number of racial attacks and the Rodney King beating in March 1991.

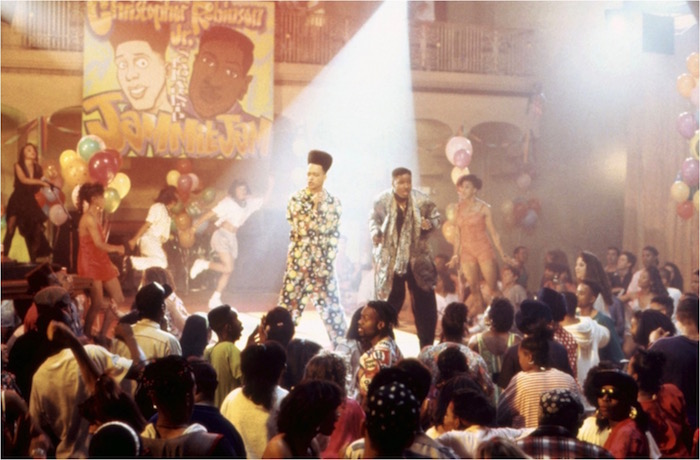

“Our style was to have images that immersed the audience in the story by conveying the emotional or psychological states of the characters and the feeling of the environments,” said Ernest Dickerson, the cinematographer on several of Lee’s early movies, including 1991’s “Jungle Fever,” about a doomed interracial romance, starring Snipes and Annabella Sciorra. They often experimented with color, to denote different phases of the narrative, and storytelling techniques, like having the characters address the camera directly.

Wesley Snipes, left, Veronica Webb, Spike Lee and Annabella Sciorra in ”Jungle Fever.” (©Universal/Courtesy Everett Collection)

For Burnett’s poetic debut film, “Killer of Sheep,” which opened in 1991 (more than a decade after it was shot), he cast neighborhood friends and kids, who also did lights and sound. With the film, about a Watts man who works in the slaughterhouse, he wanted to create a more nuanced perception of the black community. “Hollywood perpetuates so many wrong ideas about [us],” he said.

That’s in part because black directors had a hard time breaking in. When Harris couldn’t get past the assistant’s assistant in Hollywood, he decided to raise the money for his debut feature from private investors. It took him four years. “Chameleon Street” is a darkly comic biopic about Douglas Street Jr., a con man who assumed the identities of a reporter, attorney and surgeon (he performed dozens of successful hysterectomies) before getting caught. Harris said Street, whom he’d first read about in the Detroit News, was rebelling against societal constraints. “You are told from cradle to grave in this country exactly who you are, what you are and where the ceiling is on your expectations,” he said.

After winning the Sundance Film Festival’s top prize, Harris was a hotly sought-after talent, but Hollywood rejected every one of his original movie ideas. Instead, one studio offered him “a movie about a guy with an arm coming out of his stomach.” He is still working on a follow-up film.

Bill Duke couldn’t get hired in film after graduating from AFI Conservatory in 1978, so he turned to television, where he worked his way up to directing episodes of “Dallas.” “I remember the times when — it was whispered, but — I was called a n—–,” said Duke, who broke into features in 1991 with “A Rage in Harlem,” a stylish adaptation of the Chester Himes crime novel starring Robin Givens, Forest Whitaker and Gregory Hines. “No one was used to being told what to do by a black man.”

Badja Djola, left, Robin Givens, John Toles-Bey and Ron Taylor in “A Rage in Harlem.” (Richard Blanshard/Getty Images)

If finding work was tough for the men, it was like winning the lottery for black women. “Of course it bothered me,” said “Daughters of the Dust” director Dash. “I knew many female filmmakers, but at the time the language being spoken in Hollywood was hip-hop, urban [male]. Women did not fit into their myopic view” of black life.

Many directors made the savvy move of casting rappers such as Ice-T in major roles and featuring them on the soundtracks.

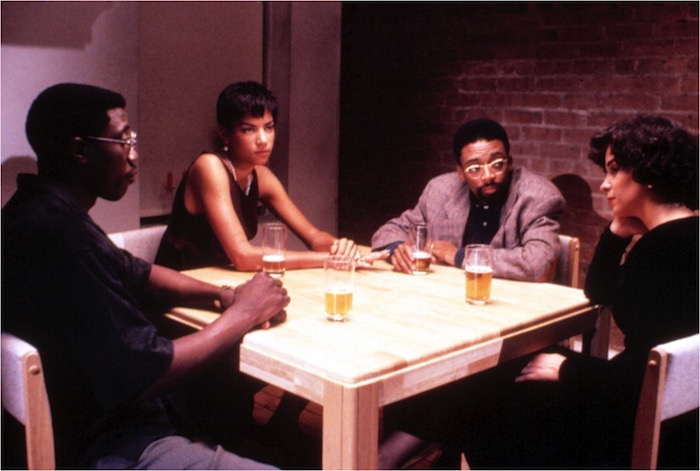

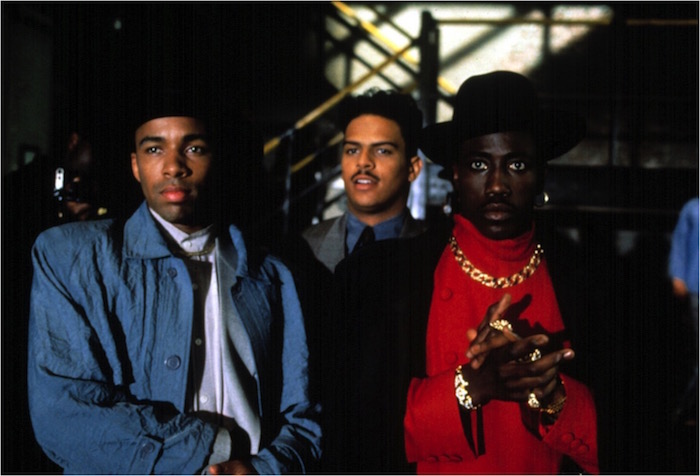

“Even ‘New Jack City,’ quiet as it’s kept, was designed as a platform for the music,” said a half-joking Snipes, who modeled his ruthless crack kingpin character after a Fortune 500 CEO.

The movie’s director was Mario Van Peebles, who said he tried to make it like “a brother in the basement making hard-core rap records.” He fought the studio to shoot on location, picking an area of Harlem controlled by drug dealers. He also refused to rely on stock footage for the famous opening scene, with its booming hip-hop track and helicopter shots of Manhattan that push in on Snipes dangling a man over the Queensboro Bridge.

Judd Nelson, left, and Ice-T in “New Jack City/” (©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Collection/©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Collection)

“When they saw that first shot, people in theaters went crazy,” Van Peebles said. The black gangster picture grossed an impressive $48 million. Like father Melvin’s 1971 film “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” — credited with starting the Blaxploitation genre — “New Jack City” turned out to be a watershed in black cinema, with a hit soundtrack. “History doesn’t repeat itself, but, boy, does it rhyme,” Van Peebles added.

In the early days of the movement, Singleton, Dickerson and others would gather at the L.A. homes of Van Peebles and Hudlin for Thai food and to swap stories, rap about technique, toss around ideas until 5 a.m. and commiserate about the business.

“A lot of times people presume we are the movies we make,” Hudlin said. “Very often that’s true. But sometimes the movies we make are the movies we can get made.”

Allen Payne, left, Christopher Williams and Wesley Snipes in “New Jack City.” (©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Collection)

The sets were social, too. “It didn’t feel like work,” says Ruth E. Carter, who designed costumes for three black directors in 1991. “It was like we were going to hang out with friends who happen to be directors, actors, ADs, PAs.”

When Carter, now a two-time Oscar nominee, broke into the business in the late ’80s, movie crews had about as much diversity as a NASCAR pit crew. So she said Lee’s company, 40 Acres and a Mule, launched an internship program to train techies and craftspeople. Others followed his lead, and the crew for “Boyz N the Hood” was 90 percent black.

Once Hollywood realized it could make big profits on black films, there was a frenzy for material, leading to such films as “Juice,” “Malcolm X” and “Passenger 57.”

Today, despite the absence of black acting Oscar nominees in the past two years, more blacks are getting a seat at the Hollywood table. Nate Parker’s “The Birth of a Nation” is already generating Oscar buzz, as is “Fences” with director-star Denzel Washington. Ryan Coogler (“Black Panther”) and F. Gary Gray (“Fast 8”) are helming big-budget movies, and Ava DuVernay is adapting “A Wrinkle in Time” for Disney.

Nate Parker’s “The Birth of a Nation,” coming out later this year. (Fox Searchlight Pictures/Fox Searchlight Pictures)

“The things we’ve been shouting into the wind for 40, 60 years are finally being acknowledged, like: ‘Oh! If a movie is multi-ethnic, it appeals to more people and makes more money. And having directors with different points of view can mean something to the audience,’ ” said Hudlin, who is working on a movie starring Chadwick Boseman as Thurgood Marshall.

But Singleton is nervous about the way black directors are treating the issue of race. “A lot of them want to assimilate into the so-called mainstream and make the black version of this or that movie,” said Singleton, who is developing two TV shows. “They don’t understand that, by being Afrocentric and African American, we were trendsetters.”