Conor McGregor and the Great Alt-Hype

Floyd Mayweather vs. Conor McGregor has been called an “existentially meaningless fight” but that’s not to say the spectacle is.

by

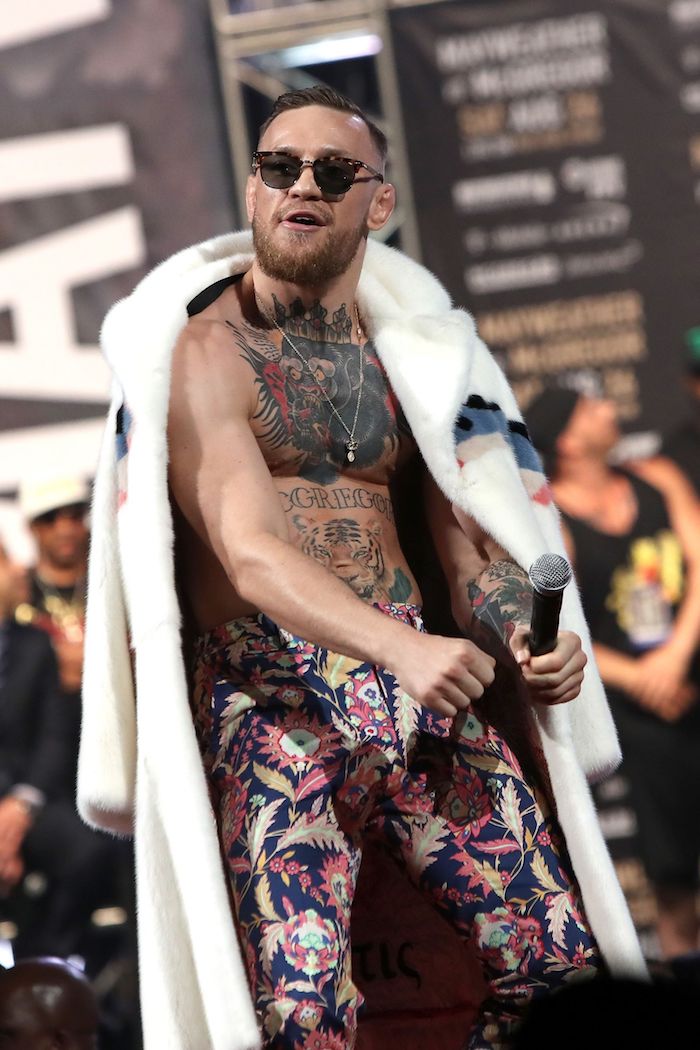

If you want to know how we got to Voltron references, mink coats in July (in Vegas), and just good ‘ole fashioned toxic stupidity, you don’t have to go very far. This weekend’s boxing match will end exactly the way it began; as a failed punchline to a gruesome joke.

It’s fitting then, that this was all predicted, outlined, and explained in 1996. Reginald Hudlin’s The Great White Hype illuminated the the presence and politics of Floyd Mayweather vs. Conor McGregor. This wasn’t Demolition Man – a silly film hitting the Nostradamus bingo with a good joke. It was ancient wisdom articulated by Samuel L. Jackson and Damon Wayans.

In the film, Jackson plays a bombastic, greedy boxing promoter. His current champ, James Roper (played by Wayans), is a great fighter. Roper doesn’t have any interesting challengers lined up, and thus can’t make the promotion money. So Jackson finds himself a ready-made narrative – scout for white fighters to challenge his black boxer. This white fighter (Terry Conklin, played by Peter Berg) will have no real credibility, but ‘race sells’.

The fight gets approval from the athletic commission. The commissioner, played by Cheech Marin, eventually agrees to the absurd spectacle. How? “Money, sex, and drugs,” he tells Jackson. Meanwhile, a journalist played by Jeff Goldblum is blacklisted because every good freakshow has a subplot that makes perfect sense in prizefighting’s bizarro world of petty grudges and vulgar displays of power.

Let’s look at these parallels.

Inside the cage, when the UFC instituted its Reebok partnership, the only bonuses ‘comparable’ to the independent sponsors that fighters used to have would be granted to only 2 percent of the roster. The cap on Reebok’s “lucrative” deal is just 4 percent of what Floyd Mayweather makes in Burger King sponsors alone (likely another form of the UFC’s cost cutting).

Inside the ring, Olympic boxing was recently accused of blatant corruption after a series of questionable decisions in Rio – something Mayweather himself was the victim of in 1996. Several years ago, the death of boxer Beethaeven Scottland occurred while the New York State Athletic Commission was in the middle of political patronage.

Bombastic, greedy promoters? Check.

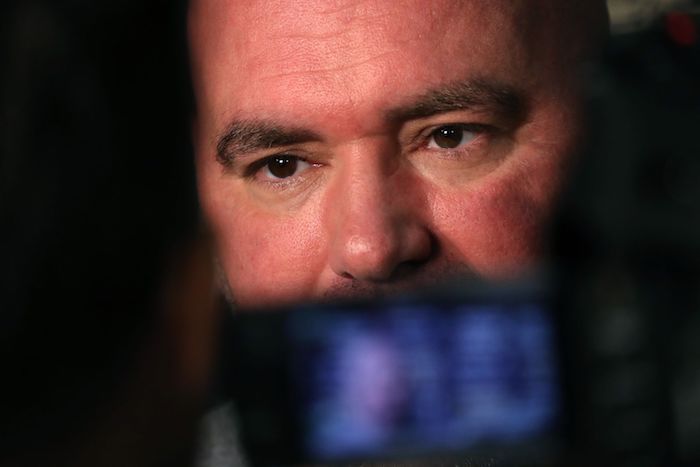

What about the seedy athletic commissioner? Bob Bennett strenuously objected to any implications that money had anything to do with approving a fighter with no boxing history against a fighter with one of the most decorated histories in the sport.

“Money had nothing to with it,” he told Ariel Helwani. Which sounds sincere enough in a politically compromised way. That is, until you begin cataloging the things Bennett starts saying afterward that turn you into a Drew Scanlon meme.

“Conor is the younger, stronger, the longer, more powerful puncher.”

“He’s a young, aggressive warrior.”

“Conor is a young warrior coming up.”

“Mr. Hunter thought that if Nate (Diaz) really wanted to be a professional fighter, he would have been a world-class boxer.”

“Money, sex, and drugs.” (just kidding)

What about the Jeff Goldblum role, in which a journalist is blacklisted because prizefighting is a bizarro world of inexplicable subplots? Check.

And to think it all started because an Esquire journalist casually asked McGregor about Mayweather, and McGregor replied that he’d “kill him in less than 30 seconds.” To be fair to Mayweather, them’s fighting words (with historic implications).

A fake poster from Mayweather, and an Iron Man text later, and the fight was on.

The boxing media, as expected, haven’t taken kindly to the match. They’ve called it an absolute insult. The Washington Post has dubbed it dubious. And Sugar Ray Leonard called it embarrassing.

The MMA media has been less quiet, but they know what it’s like when the glove is on the other hand. They used the exact same language when James Toney fought Randy Couture in a soulless display of regrettable actions for everyone involved.

My colleague, John Nash, has called the bout a hippodrome; a nice bit of Grecian terminology referring to something ‘not on the level’.

There’s an interesting dynamic in the ’96 film. Roper is portrayed as greedy, uppity, and lazy. That last characteristic is symbolized by Roper doing laps trying unsuccessfully to catch an ice cream truck. Conklin, meanwhile, is portrayed as clean cut, and nonviolent. In fact, Conklin’s participation relies on Sam Jackson’s character convincing him that the $10M he’s paying him can eradicate homelessness.

McGregor hasn’t talk about eradicating homelessness, but the media has made a big deal about McGregor collecting a welfare check. I guess we’ve long since forgotten that Mayweather grew up coming home from school with heroin needles littered on his front lawn. Of course, growing up around filth doesn’t prevent someone from becoming filth themselves. Nonetheless, it does beg the question. If there’s nothing sincere, or legitimate about this fight, then why the hell is it happening?

Is it because this match represents a much older fight?

Don’t look at me. The topic of race was broached by the fighters themselves. When McGregor said “dance for me boy” during the unrelentingly stupid world tour, Mayweather naturally accused McGregor of being racist. In the interest of word count, I’ll skip the part where both followed the discussion up with words like “faggot” and “I’m black because I have a black cock” (in so many words) as if this circus wasn’t #problematic enough.

Indeed, McGregor doesn’t exactly have a sparkling resume when it comes to his ‘gift of gab’. He called Nate Diaz a “cholo” and told Jose Aldo he’d “invade his favela”.

Boxing itself understands these tribal boundaries. It was the rallying cry for Jim Jeffries to challenge Jack Johnson, the first black boxing champion in 1910, instigated by the American novelist Jack London, who cried “Jeffries, it’s up to you! Jeffries, it’s up to you! The White Man must be rescued!” Fitting, since London himself believed in eugenics.

“Unlike other major sports, where athletes are routinely fined for using slurs and making offensive statements, boxing virtually stands alone — a warped and backward dimension of the sports world where racism, sexism and the ugly underbelly of American hate is strategically showcased to generate interest and sell tickets. The Mayweather-versus-McGregor promotion is an extension of this checkered history and institutional culture, but this time, the stage is far bigger and the stakes much higher,” Kahled A. Beydoun writes.

Which is true. Boxing seems to enjoy swimming in its own sewage. Other sports aren’t perfect, but there’s at least a pretense of civilization. Anaheim hockey all-star Ryan Getzlaf was fined for calling a ref a cocksucker. Kobe Byrant’s gay slur cost him $100,000. And NFL players can’t go to Vegas to arm wrestle.

But not prizefighting. In the UFC, when Mike Perry’s cornerman made fun of the eyes of Perry’s South Korean opponent, Lim Hyun-Gyu, the UFC just looked the other way. Like they did with Bisping and Cerrone. This isn’t even counting the presence of the bizarre but uglypost-Soviet geopolitics.

The UFC mirrors this raw divide. The sport itself has become a “bifurcated product”, as Patrick Wyman observes, thanks to an incredibly small pool of actual sellers (Ronda Rousey, Conor, and Jon Jones before he looted Manfred Ewald’s coffin for his remaining stash) complimented with a travel bag of fighters that sell some vague notion of the UFC product rather something truly identifiable. If that sounds abstract, consider what Jon Anik told Wyman; that market research revealed that a third of UFC viewers on Fox don’t even know that they’re watching the UFC.

Floyd and Conor don’t explicitly bear the burden of racial tensions in America, or Soviet geopolitics. But the implicit feeling of being burdened by a system that only ever pressures, never relieves, is nonetheless familiar. It’s not their respective sports that brought them here. That’s part of it. It’s their personalities. These are men trying to rise above their sports. Not with them. By Floyd’s own admission. And Conor.

This is not the story boxing, or the UFC would ever tell of course. It has to be packaged the way it always has; as tribal warfare with a mic.

“Alt”, in recent years, refers to a combining form denoting extremism – a fitting description for a hyped fight in which faith in one fighter relies on the similarities between a non-boxer andcryptocurrency.

In Hudlin’s film, Conklin loses the fight by knockout. Hudlin juxtaposes Conklin’s loss with a crippled boy, rooting for Conklin, dropping his arena-bought Irish flag in despair. Maybe it’s just me, but I don’t believe there’s a single possible outcome on Saturday that won’t leave us feeling like that crippled boy.