It’s Thurgood Marshall to the Rescue in a New Thriller

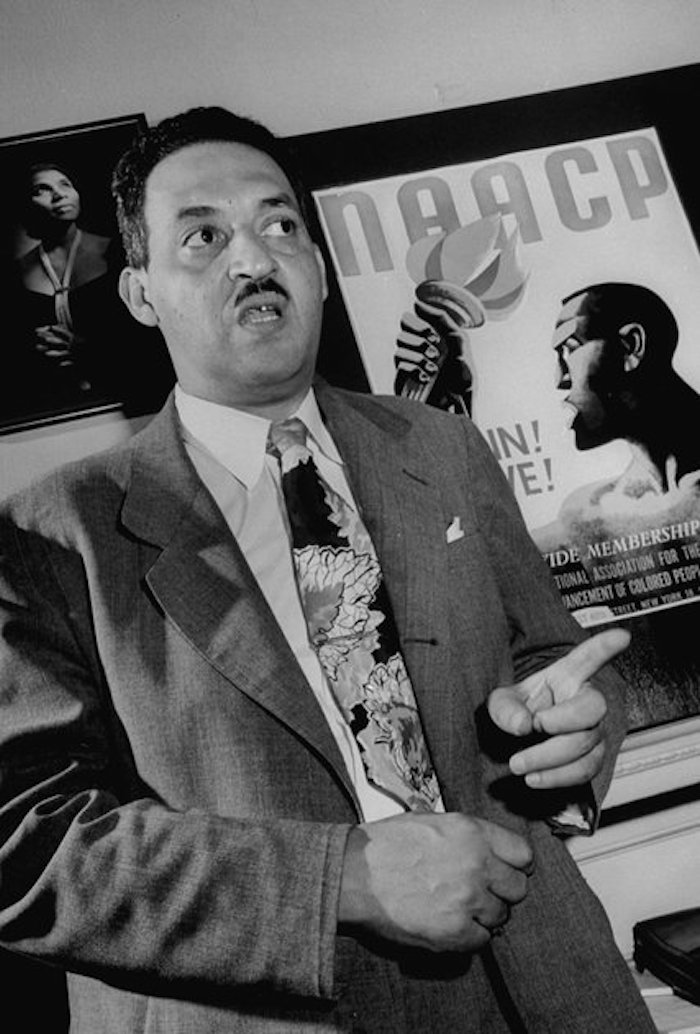

Chadwick Boseman in “Marshall,” directed by Reginald Hudlin and opening Oct. 13. Credit Barry Wetcher/Open Road Films

Thurgood Marshall would be a good candidate for a dusty and dutiful biographical drama, one surveying his central role in Brown v. Board of Education, the towering 1954 civil rights landmark, and his years as the Supreme Court’s first black justice.

That is not the movie the director Reginald Hudlin wanted to make. He had in mind a brisk, entertaining and urgent look at a single episode early in Marshall’s career.

“It’s not a cradle-to-grave biopic,” Mr. Hudlin said of the film, which is about a lurid rape trial the lawyer handled in 1941, when he was just 32. “It’s a courtroom thriller,” he said. “It’s a whodunit.”

Marshall is portrayed by Chadwick Boseman, who has starred in more comprehensive biographical dramas, playing Jackie Robinson in “42” and James Brown in “Get on Up.” In the new film, Mr. Boseman said, he was focused on his subject at a formative moment. “I wanted to capture his personality, his swagger, his love of life, his sense of humor,” Mr. Boseman said. “And his ambition.”

“Marshall” (due Oct. 13) arrives at a combustible time, and it has a message. “We are at a time when the country is literally being torn apart,” Mr. Hudlin said. “Black voices constantly fighting to be heard is tragically very, very current.”

Protest and resistance are important, he said. But so is working within the system. “We can’t just fight the power,” Mr. Hudlin said. “We have to be the power. That’s what Thurgood Marshall was. He was a guy who fulfilled the promise of the Constitution.”

The film’s version of the future justice, who died in 1993, is both realistic and relentless. “The Constitution was not written for us,” Marshall says. “We know that. But no matter what it takes, we’re going to make it work for us. From now on, we claim it as our own.”

In his later years, he came to be known as a superb appellate lawyer and litigation tactician. But his early career was spent in trial courts, mostly in the South, where he fought for racial justice in hostile territory, relying on humor, charm, outrage, guile and stone-cold courage.

In a twist, the film focuses on a trial in Bridgeport, Conn., where Marshall had to hone and adapt his talents to address a social structure and legal system that was stacked against black defendants in less obvious ways than in the Deep South. Mr. Boseman said the setting makes the film all the more timely. “It pinpoints the more subtle version of how racism affects America,” he said.

The defendant, Joseph Spell, played by Sterling K. Brown (the prosecutor Christopher Darden in “The People vs. O.J. Simpson”), was a black butler and chauffeur. He was accused of rape and kidnapping by his employer, Eleanor Strubing, a white socialite from Greenwich, Conn., played by Kate Hudson. The case captivated the New York tabloids and led rich white families in affluent New York suburbs to fire their black servants.

In “Devil in the Grove,” which won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction, Gilbert King wrote about Marshall’s heroic trial work. “Across the South,” Mr. King wrote, “in their darkest, most demoralizing hours, when falsely accused men sat in jails, when women and children stood before the ashy ruins of mob-torched homes, the spirits of black citizens would be lifted with two words whispered in defiance and hope: ‘Thurgood’s coming.’” (A film adaptation of “Devil in the Grove,” which focuses on a different case, is in the works.)

“Marshall” touches on some of those Southern cases, too, and in places the legal thriller is tinged with touches of other genres. “I also kind of see it as a western,” Mr. Hudlin said. “It’s a movie about Thurgood Marshall. And he’s the marshal. He’s like Shane. This guy goes from town to town dispensing justice. So that title was chose very deliberately because that really sums up that era of his life.”

If the film is part courtroom drama and part western, it is also buddy movie. Marshall’s local counsel, Samuel Friedman, played by Josh Gad, is a white, Jewish insurance defense lawyer with modest skills beyond a knack for spotting technicalities. Marshall takes him in hand and transforms him, sometimes playfully and sometimes forcefully.

“At the beginning of this movie,” Mr. Boseman said, “Sam Friedman is not in a place where he is willing to take a stand. It’s Thurgood Marshall that smacks Sam on the top of the head and says: ‘This is you. This is your injustice. This does touch you.’”

“I love the movie for that reason,” he continued. “It doesn’t allow you as an audience member, no matter what color you are, to hide from the issues because ultimately we see ourselves in the characters in the movies we go see.”

Mr. Hudlin said his film was about allies. “When I think specifically about the black-Jewish alliance and how many things it’s done for this country — in government, in the arts — that partnership is a little frayed,” he explained. “This movie celebrates the achievements of that partnership.”

“Marshall” has elements of yet another genre. It is a sort of origin story, of a legal superhero. Justice Elena Kagan, who served as a law clerk to Justice Marshall, has called him “the greatest lawyer of the 20th century.”

“Bar none,” she added. “Not even a close contest.”

Mr. Hudlin and Mr. Boseman know something about superheroes. Mr. Hudlin spent years writing “Black Panther,” the Marvel comic, and Mr. Boseman played the character in “Captain America: Civil War” and next year’s “Black Panther” and “Avengers: Infinity War.” The filmmakers said “Marshall” works, as origin stories should, even if the audience arrives at the theater knowing nothing about its central figure.

From left, Josh Gad, Chadwick Boseman and Sterling K. Brown in “Marshall.” Credit Barry Wetcher/Open Road Films

The film would have been compelling even if he were named John Smith, Mr. Hudlin added. “But he also happens to be a real person, and he was the greatest lawyer in the history of the country.”

People who knew Marshall said the film captures his swagger, humor and love of life. “He had a legendary capacity for spontaneous humor and telling anecdotes,” said Deborah Rhode, a law professor at Stanford who served as his law clerk.

The film includes glimpses of Marshall’s glittering, jazz-infused social life in Harlem, including friendships with Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. The young lawyer drinks, flirts and teases.

In court, Mr. Boseman said, Marshall drew on the improvisational verve of Harlem’s culture. “He brings that jazz to the struggle,” he said.

Mr. Hudlin said he wanted to show that the black experience in America was not only suffering and struggle.

“These guys led amazing lives,” Mr. Hudlin said. “Thurgood left that. He left his beautiful wife. He left his celebrity friends to literally go to hell, to go to places where they would kill him as easily as they looked at him. That is a different definition of courage. It’s not because your back is to the wall and you have no choice. He had a choice. He made a choice.”

“Marshall” may inspire some young people to consider law school, Mr. Hudlin said. “They’ve grown up in such a cynical time,” he said, “that they’ve never seen the law used to make things better.”

In the film, Friedman grows to admire Marshall’s ability to put out legal fires kindled by racism. Marshall rejects the compliment. “It’s not the fires I’m after, Sam,” Marshall says. “It’s fire itself.”