BLACK HISTORY MONTH WITH THE HUDLIN FAMILY

PETER HUDLIN by Richard Hudlin, PhD

Peter Hudlin and his two brothers either escaped or bought their freedom from a plantation in Virginia and all went on to be freedom fighters. Centuries later, three Hudlin brothers grow up on a street named Virginia Place in East. St. Louis. Amazing coincidence, huh?

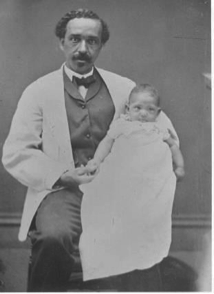

Peter Hudlin & daughter

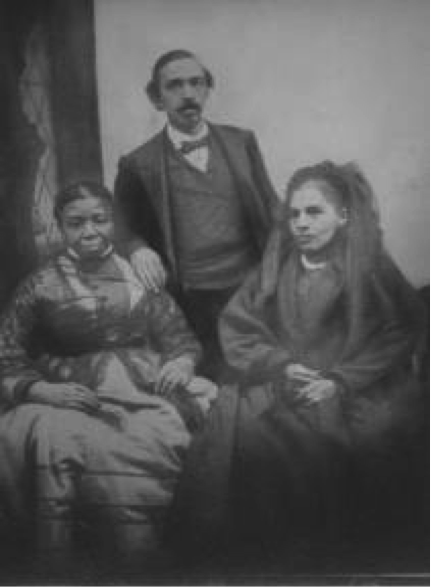

Peter’s mother, Sarah, (on his right), Peter (standing), & Peter’s Wife (on his left). I have no picture of Peter’s father, Joseph, nor of Peter’s grandfather, Joe.

Nancy Jane Rutledge Hudlin (Peter’s Wife)

Peter Hudlin was born in Virginia about 1828 and his wife, a Cherokee born Nancy Jane Rutledge in Kentucky about 1833. According to Hudlin Family oral history and other sources, great-grandfather Peter Hudlin was a conductor on the underground railroad. For example, in 1976 Josephine Lockhart wrote:

The human cargo would arrive at Peter’s home in crates. He would uncrate the run-away slaves, feed them and provide space for them to rest in his basement until nightfall. He would then recrate them and under cover of darkness, load the crates onto a wagon and drive across the river to one of the two major underground routes northward near Alton, Illinois.

Peter Hudlin joined the Knights of Tabor, a secret society which included a separate and even more secretive inner circle which planned, organized, and prepared to end chattel slavery by force of arms. The first battle of the guerrilla war was planned for Atlanta, Georgia. John Brown’s raid and the subsequent public reaction led to postponement and finally, when the Civil War began, cancellation of this effort in favor of recruiting African-Americans and others opposed to slavery for enlistment in the Union Army. Mr. Hiram Revels (later the first African-American Congressman from Mississippi) organized a regiment in St. Louis when Peter’s son, Richard A. Hudlin (1858-1918), was five years old.

Aside from treason, aiding and abetting fugitive slaves, and aiding and abetting African-American literacy, Peter and Nancy were law abiding, ethical, and moral. He took care to admonish his children whenever they engaged in unprincipled behavior.

No one who asked for food was ever turned away. I suspect that hobos placed some mark on his premises so that other hobos would know that the Hudlins would feed anyone.

In Peter’s day African-Americans were generally denied public accommodations in St. Louis, so travelers stayed at peoples homes. Many famous people were frequent guests at his home (and his brother Joseph’s home in Chicago), including Frederick Douglas, who was the undisputed leader of African-Americans at home and abroad.

Peter’s devotion to education is further revealed by the fact that his son, Richard A. Hudlin, was one of the small number of Americans of African or native American ancestry who graduated from a “white” college in that era.

Peter Hudlin’s Brothers

Samuel Hudlin made friends with the captain of a ship, who smuggled him on board in a barrel, and dropped him off in New Brunswick, Canada where he settled, bought land, and raised a family. Canada had abolished slavery before Samuel arrived, so he was safe there. He also earned enough money to send for some of his family members, which had to be done discretely and diplomatically since many Canadians were hostile to people of African descent coming to Canada.

Thanks to the compassion of their owner, Peter Hudlin and a least one of his brothers, Joseph, were allowed to keep some of the money they earned.

Joseph Hudlin left with his earnings, without buying his freedom, and settled in Chicago in 1854. At that time, there were many free African-Americans and its climate of opinion was such that he was relatively safe from capture and return to slavery.

Joseph was also a conductor on the underground railroad and his house was one of the Chicago underground railroad stations where fugitive slaves ate, rested, and prepared for a life in Chicago, a trip to Canada (sometimes on a ship sailing from Chicago), or a trip elsewhere. It is possible that some of the fugitives Peter Hudlin drove into Illinois stopped at Joseph’s house in Chicago.

Peter Hudlin used some of his earnings to buy his freedom and left Virginia, met his future wife in Kentucky, visited his brother Joseph in Chicago (where both decided, planned, and prepared to help fugitive slaves as conductors), and eventually settled in St. Louis, hoping that the papers documenting his freedom would save him from being seized, declared (illegally) to be a runaway slave, and enslaved. Were this to happen, the person who seized Peter would be likely to declare such papers forgeries (or simply destroy the papers), and only a contrary statement by a European-American would be likely to be credible confirmation that Peter was free.