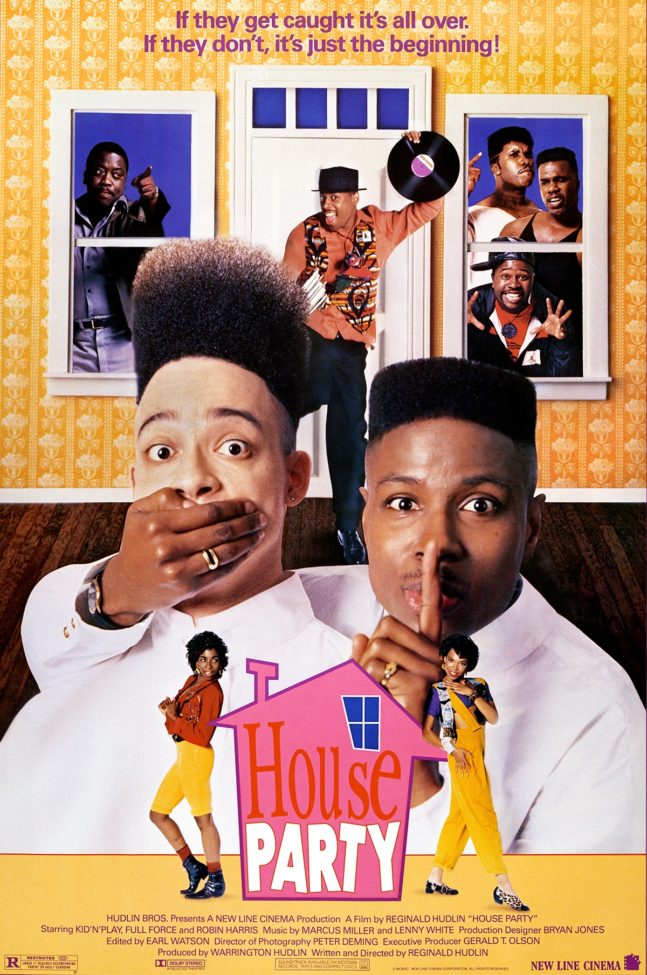

‘HOUSE PARTY’ IS A CLASSIC COMEDY THAT SHOWED BLACK KIDS BEING THEMSELVES

Reggie Hudlin’s classic comedy’s enduring appeal lies in its specific cultural voice.

It’s been 30 years since the release of House Party, the enduring Reginald Hudlin-directed teen rap comedy starring Kid ‘N Play. In those three decades, the popular movie has spawned an entire franchise (with an expected reboot on the way), turned Kid ‘N Play into pop culture superstars (remember the cartoon?), led to some cast reunions and retrospectives, and made it a fixture on most lists celebrating classic Black movies. It’s uniquely timeless: a movie draped in Black culture, an ode to Black teendom and a film that celebrates the universal, youthful release that hip-hop has always been able to provide.

The film was born of a 1983 short that was shot and produced by Hudlin while he was still a student at Harvard. In 1987, brothers Reggie and Warrington Hudlin turned the short into a full feature script, presenting it to New Line Cinema, the movie studio then predominantly known for the Nightmare On Elm Street horror series. Looking to hop on the post-Spike Lee Black film wave, the studio greenlit the movie. Initially written for Grammy-winning pop-rap duo DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, the starring roles instead went to their contemporaries Kid ‘N Play, a pair of fleet-footed rhymers from Queens who’d enjoyed a string of rap hits helmed by superproducer Hurby “Luv Bug” Azor. A virtually unknown Martin Lawrence soon joined the cast as Kid ‘N Play’s hapless buddy, Bilal—fresh off his first big screen appearance in Lee’s 1989 classic Do The Right Thing.

As the film’s two female leads, Sidney (Tisha Campbell) and Sharane (A.J. Johnson) are at the center of both the film’s romantic conflicts and their own semi-rivalry. The two actresses already knew each other when House Party began casting.

“I was just coming out of In Living Color,” Johnson recalls to VIBE. “[My attorney] was also the attorney for Reggie and Warrington Hudlin. He told me there was a film he was representing that I was perfect for. They were looking for a brown-skinned dancer, high energy, attitude, fun loving–and that’s kind of where it began. By the time he set up my audition, it was actually a pairing for the Sidney and Sharane roles. At the time, Tisha was my friend but more my mentor. Because at that time, I was a dancer. I’d done little bits of acting, but more so dancing. She said ‘I’ve got an audition for a movie called House Party!’ I said ‘Me too!,’ and she was like ‘omigod! Let’s go at the same time!”

On-set, Johnson admits that she didn’t get the movie initially. But she focused on the bond between she and Campbell’s characters.

“Not at all!” she says with a laugh when asked if she knew at the time that this project was special. “I didn’t get the humor. I didn’t live in the projects, so I [didn’t] understand half these lines and jokes. [But] Tisha and I were creating this friendship. So because Tisha was the thespian between the two of us, she was very strong in saying ‘Let’s create a friendship that other sisters will want to emulate.’”

The soul of House Party was the late comedy legend Robin Harris. As “Pop,” Harris was the grumpy-but-hilarious dad–attempting to catch his wayward son, Kid, after the teenager sneaks out to attend the shindig at Play’s house. It would be Harris’ biggest role, and sadly, his last. He died of a massive heart attack just days after the film hit theaters. But the movie became a major part of a legacy that has continued in the decades since his death. The late John Witherspoon also makes a memorable appearance as an angry neighbor—one of many scene-stealing appearances he would have in classic Black comedies throughout the 1990s.

A box office hit in the spring of 1990, House Party was a trailblazer. After a decade of classic 80s teen movies like Weird Science and Pretty In Pink, films that mined the angst of coming of age but from a decidedly white perspective, here was a film telling a story of Black teenage culture at the dawn of the 1990s. Critics raved, and took note of House Party’s uniquely African-American lens.

In 1990, the Los Angeles Times wrote:

“Shot for $2.5 million with a nearly all-black cast and a crew the Hudlins tabulate as 65% African-American, the film is loaded to the max with specific references–jokes, fashion, dance, music, language, products, politics–to the black teen-age hip-hop subculture. Combined with the film’s ethnic wit and edge, and its raucous energy, it adds up to a cultural richness rarely found in standard teen comedies.”

The then-28-year-old Reggie Hudlin believed that authenticity is what resonates universally. “The theory we’ve always believed…is that if you can make a film that is culturally uncompromised, it will still have broad appeal. And, in fact, by diluting the (ethnic content of) the film, it becomes less interesting for all audiences.”

In making the film, both Hudlin and the cast tapped into a wealth of experiences. The movie’s iconic dance scene was the brainchild of Johnson, who’d attended Spelman College in Atlanta and felt no party could be a party without a dance battle. “I was coming from a dance battle environment,” she explains. “I was at an HBCU. I pledged Delta Sigma Theta Incorporated. So between stepping in a sorority and being at Spelman, all I knew at parties were dance battles. When I got to the script and there was no dance battle, I said to Reggie ‘I don’t know how to party without a dance battle!’ And he said ‘Well–let’s see what that looks like.’”

Part of why House Party resonated then and continues to now is that kind of warm authenticity. Sure, its R-rating is earned—there is no shortage of raunchy jokes—but it feels true to Black teenage experience in a way that audiences hadn’t seen in a major film since Cooley High. These were young Black people who aren’t sanitized—they face issues like cop harassment, after all—but who also aren’t “at-risk” necessarily, and whose lives aren’t neatly divided into stereotypical boxes. The movie shows you Black kids from the projects and from middle-class suburbia—and they don’t seem all that far away from each other, geographically or culturally. It was shot in L.A. but never looks or feels like the same backdrop as Boyz N the Hood or Colors; it feels like this story could be anywhere in Black America.

“For that to be my first true starring theatrical role, it spoiled me,” says Johnson. “It was hard to do anything less than the collaborative energy that Reggie gave. It was very respectful and he honored each of our talents: he honored the comedy in Martin; the comedic timing in [co-star] Daryl ‘Chill’ Mitchell; he honored the camaraderie and teenage female energy between Tisha and I; he honored what Kid N Play had already established as Kid N Play even offscreen, and then he honored what he was watching as we moved through the film. He’d witnessed all of it. He was just basically there to nurture more chemistry and more good times. After that, it was hard for me to work with other directors who are not as collaborative.

“It’s almost like Reggie gave me the permission to be the true artist I was. A lot of directors, they tell you your mark, they tell you how to say a line—and that’s ok, that’s the director’s style. But because my first experience as a lead in a film was Reggie Hudlin, it was hard for me to work with another director that was more constricting.”

In 2016, Lawrence told Collider: “Well I was just young and I was new to the game and I was so excited to be part of all that. I was just very happy and eager to get my career going and people to know who I was. You know, just deliver. Become somebody to be reckoned with and that’s why I was so excited about that time.”

It’s not hard to understand why House Party still resonates. Everything from the clothes to the music speaks to its era in a way that honors that moment in time; and with its honest depictions of youthful Black exuberance, every generation of teenagers finds themselves relating to the antics onscreen. Beyond just teens, it feels like a love letter to Black pop culture; it references everything from Dolemite routines to the Hey Love R&B compilation commercials (“No, my brother—you got ta buy ya own”) to P-Funk chants, with a kinetic soundtrack that features R&B and hip-hop from the likes of Full Force (who also famously appear as high school bullies in the film) and Public Enemy. This was a movie unafraid to be as Black as it could possibly be, and it helped to announce the wave of Black cinema that would define the early 1990s.