Django Unchained Producer's Diary: Part I

An Inside Look at the Making of One of the Season’s Most Anticipated — and Controversial — Movies

By Reginald Hudlin From Ebony Magazine

First Day of Production

As dawn breaks on the Django Unchained set, the first shot of the movie starts. Christoph Waltz, Oscar winner from his work with Quentin Tarantino in Inglorious Basterds, drives a dentist’s wagon with an oversized tooth on a bouncy spring into the Western town. Next to him, a Black man is on horseback. It’s Jamie Foxx, Oscar winner for his work in Ray, playing the lead role of Django. His hair and beard make him look like a cross between Jimi Hendrix, a young Gil Scott-Heron and a very youthful Frederick Douglass. He’s wearing a bloody coat and hat he took from the slavers he is now free of. No shirt. In the distance, we hear the sound of a hammer driving nails into a hangman’s scaffolding.

When the women on the set see Jamie, there’s a quiet intake of air from all of them. He’s not trying to be sexy. In fact, he’s grimy and filthy. But Jamie’s also in peak shape, and the image of a Black man on horseback — bloodied but not bowed — is so striking, it creates an electric charge that everyone feels.

Jamie’s horse belongs to him, meaning he was already a rider with his own horse when he met with writer/director Quentin Tarantino about playing the lead role in the film. I don’t know if a Western star has appeared with his own horse since Roy Rogers and Trigger, but it’s one of the many reasons why Jamie is perfectly cast in the role. It’s a physically demanding part that required months of quick-draw training, working in the subzero temperatures in Wyoming and the humid summers in New Orleans. But Jamie bears it all without complaint. He knows the ancestors he’s representing onscreen endured miseries we can’t imagine. The least he can do is experience a fraction of their pain to make sure his performance is accurate.

Third Month of Production

We’re shooting on Plantation Row in New Orleans. I had never been on a slave plantation before, and the natural beauty of the old South, with Spanish moss hanging off the overarching trees, provide an ironic contrast with the slave shacks below them where horrible crimes against humanity were committed on a daily basis. The ghosts are still there. As tour buses playing clips from Gone With the Wind drive past, I am happy to be working on a film that will tell the truth about the brave men and women who fought back.

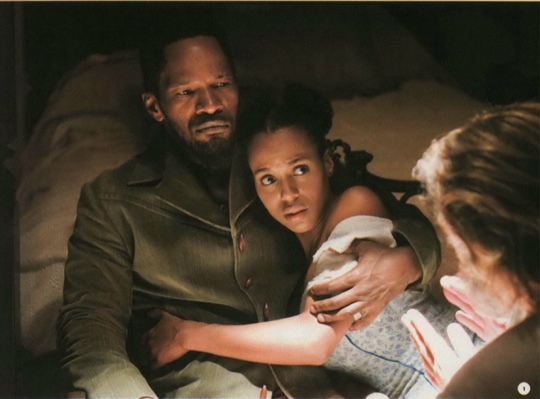

When we were shooting in California and Wyoming, we were focused on the "Western" aspects of the movie. Now we’re focused on the South, and it’s been a tough week for the cast and crew. Watching actors playing villainous overseers who tie a young woman to a tree stump as they prepare to whip her for breaking eggs has everyone on edge. While Cooper Huckabee, as Little Raj, tightens the ropes around her wrists, M.C. Gainey, who plays Big John, cracks a whip in one hand and carries the Bible in the other. In a brilliant last-minute addition, Tarantino had the idea of the character patching the holes in his clothes with pages from the Bible. Big John lectures her with completely bogus quotes from the Bible, taking advantage of her illiteracy to convince her that the enslavement of Black people is God’s plan.

When we were shooting in California and Wyoming, we were focused on the "Western" aspects of the movie. Now we’re focused on the South, and it’s been a tough week for the cast and crew. Watching actors playing villainous overseers who tie a young woman to a tree stump as they prepare to whip her for breaking eggs has everyone on edge. While Cooper Huckabee, as Little Raj, tightens the ropes around her wrists, M.C. Gainey, who plays Big John, cracks a whip in one hand and carries the Bible in the other. In a brilliant last-minute addition, Tarantino had the idea of the character patching the holes in his clothes with pages from the Bible. Big John lectures her with completely bogus quotes from the Bible, taking advantage of her illiteracy to convince her that the enslavement of Black people is God’s plan.

Now the moment we’ve been waiting for is here: Django arrives, grabs the whip that was about to be used on the young woman and beats Little Raj mercilessly with it. For the whole cast and crew – Black, White, Native American and Asian – it’s a huge cathartic relief. Once payback is delivered, you can feel the crew getting giddy.

Set visitor Kenny Leon, the Broadway director who had just worked with cast member Samuel L. Jackson on the play The Mountaintop, can’t believe what he’s seeing. "I know you said he was going to whip him, but he beat him till he got tired!" He pauses, then adds, "Why can’t this movie come out next week?"

After a couple of takes, I walk over to Quentin and ask, "Between the two of us, we would know the answer to this: Is this the first time in cinematic history that we’ve seen a slave master beaten with his own whip?" Quentin goes quiet, mind racing through millions of images in seconds, then says, "Yes." We quietly fist bump, then go back to work.

As ferocious as Django is during the scene, the minute the director calls "Cut," a compassionate Jamie Foxx re-emerges and lends a helping hand to the man he was just wailing on. "It’s just a movie," Jamie would often say to put the emotional weight of the work in context.

But the most powerful statement was from one of the background actors who introduced himself as a local minister. He told me that working on the film all week had inspired one of his greatest sermons. He said that after seeing what our ancestors went through, there was no reason for them to have any hope that life would ever change. Yet they did have faith in the future … and that faith was rewarded. The proof is all of us working together on this project.

These words electrified me. I thanked him profusely for his insights and shared the minister’s story with as many cast and crew member a possible. If there was ever a sign that we were on the right track, this was it.