Variety – June 4, 2019 – Film Review: ‘The Black Godfather’

Reginald Hudlin’s doc is an affectionate introduction to music power-broker Clarence Avant.

By Andrew Barker

With: Clarence Avant, Quincy Jones, Barack Obama, Sean Combs, Berry Gordy, Clive Davis, Jimmy Jam, Terry Lewis, Bill Clinton, Jamie Foxx, Bill Withers, Snoop Dogg, Lalo Schifrin, Kamala Harris, Jacqueline Avant, Nicole Avant, Alex Avant, Jerry Moss, Jon Platt, Andrew Young, Jesse Jackson, Lucian Grainge, David Geffen, Nelson George, Hank Aaron, Jim Brown.

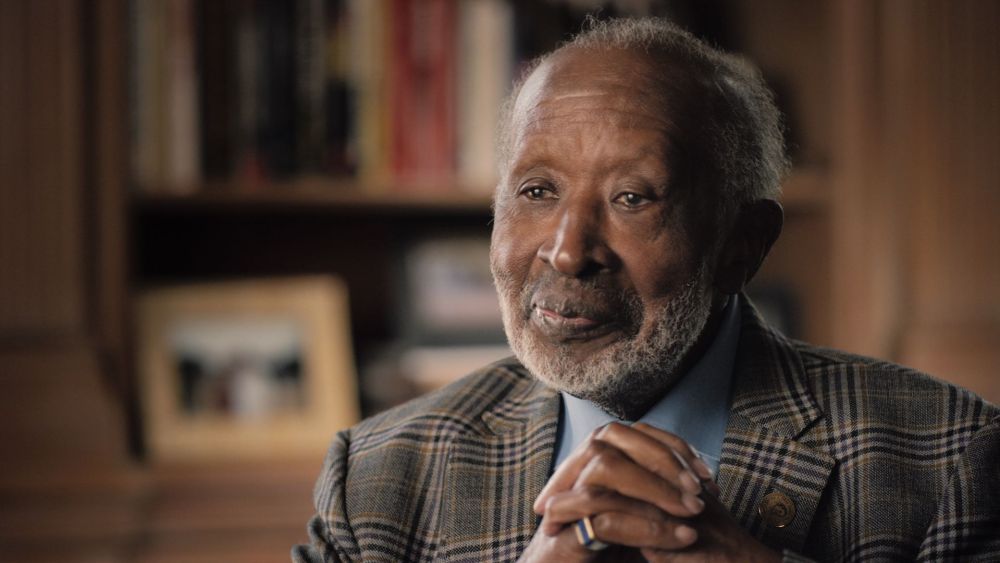

On first glance, Clarence Avant’s career highlights seem impressive, if somewhat modest for a man widely known as “the godfather of black music.” Starting as a manager to pianist-composer Lalo Schifrin, he went on to found two important if short-lived independent record labels, serve as a sporadic concert organizer and special events producer, fund-raise for Democratic politicians, and count himself as a mentor to a host of African American execs. But the 88-year-old’s impact on half a century of black music – and black enterprise in general – runs far, far deeper than that, and Reginald Hudlin’s affectionate Netflix bio-doc “The Black Godfather” does yeoman’s work introducing a figure that few outsiders have likely heard of, but who needs no introduction in the power corridors of the entertainment industry.

Perhaps the most obvious sign of Avant’s importance can be found in a brief look through the figures who agreed to sit for interviews here: From industry power-brokers (Berry Gordy, Clive Davis, Quincy Jones, Jerry Moss) to civil rights icons (Andrew Young, Jesse Jackson), Avant’s former signings and protégés (Bill Withers, Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis, L.A. Reid & Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds), and even two former presidents and one potential future one (Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, Kamala Harris). Avant’s friend circle is wide, and each of these heavyweights appear to know him intimately. Yet he was more than just a well-connected mover and shaker, and Hudlin’s film is most insightful in illustrating just how much the model of the modern black entertainment mogul was made in Avant’s image.

Profane, pugnacious, and sometimes plainspokenly profound, Avant grew up in a tiny town in North Carolina, moved to New York and fell under the tutelage of mob-connected music manager Joe Glaser, and eventually alighted to L.A., where he founded labels Sussex Records and later Tabu. But his true legacy lies in his off-the-books efforts to help other black entrepreneurs get the treatment and compensation they deserved. Whether it was advising Jam and Lewis to ask for more money, insisting that a TV network hire a black director for a Muhammad Ali tribute special, or helping save Don Cornelius’ “Soul Train” from a rival show by Dick Clark, Avant was well ahead of his time in recognizing the importance of black entertainers and athletes having an ownership stake in the businesses to which they contribute so disproportionately.

Hudlin, a longtime film and TV director here making his first documentary, does well to provide the necessary historical contexts around Avant’s biggest career moves, with the likes of Cicely Tyson explaining just how unusual it was to see a black man, much less one as colorful and country as Clarence, throwing his weight around in white-dominated industries. “The Black Godfather” is, however, produced by its subject’s daughter, Nicole Avant, and along with the access that provides comes an element of insider clubbiness that isn’t always helpful. Too often, you have to use your imagination to figure out exactly what it was Avant did, specifically, that allowed him to pull off so many impressive deals and to leave such an oversized footprint. (NFL great Jim Brown, who credits Avant with convincing him to launch an acting career, likely speaks for many in the audience when he says, “I kept hearing about this guy Clarence Avant, but no one seemed to know what his actual official title was.”)

Sometimes this is understandable – when Sean Combs mentions of Avant, “he kept my ass out of jail one or two times,” you hardly expect him to elaborate on the particulars – but it’s when Hudlin does manage to ferret out the details that a deeper understanding of Avant starts to emerge.

Hank Aaron, for example, recalls how Avant took it upon himself to secure him sponsorship deals as he inched toward Babe Ruth’s home run record – Avant’s bull in a china shop tactics to pitch Aaron for an endorsement with Coca-Cola are hilariously audacious. A more emotional side of Avant is revealed by music publishing mogul Jon Platt, who was on the verge of getting a divorce when he called up Avant expecting some “guy talk” consolation, and instead got an earful from the irate godfather. (Platt ended up patching up his marriage, and naming one of his sons Clarence.)

Unlike most music power-players of his stature, Avant has long been reticent to thrust himself toward center stage, and his sardonic, no-fools-suffered wit here helps cut through the sometimes excessive quantity of glowing testimonials the film stacks up in his honor. (The disdainful shrug he offers after conceding, “yeah, I had some hit records” is worth the price of admission alone.) But when David Geffen notes of Avant’s role as an all-purpose mentor, “I don’t know how he made a living – he never seems to charge people,” you wish the filmmakers would pose that question to the man himself. “Life is all about the numbers,” Avant says more than once here. So how did he make them add up for himself?

Perhaps, unlike most music power-players of his stature, he just understands the importance of keeping some things close to the vest.