Q&A: ‘Django Unchained’ Producer Reginald Hudlin Offers Up a Rare Inside Look at the ‘Django’ Comic Book & Quentin Tarantino’s Passion-Filled Process

When "Django Unchained" opens in theaters Dec. 25, audiences will finally see just what Quentin Tarantino has wrought with his provocative, ultraviolent slave-era Western. But that big-screen version is a long way from the screenplay Tarantino originally wrote that sparked a burst of excitement (along with juicy debate) when it first surfaced online in 2011.

Since then, scenes have been axed, dialogue has been added and major sections have been completely rewritten. Even the climax of the film was ditched — no longer does the titular character, played by Oscar winner Jamie Foxx, ride through town on his way to the Candyland plantation to blow up the master’s house. (Not to worry: Foxx himself claimed recently, "The new ending trumps it because Quentin made it a ‘ghost story.’")

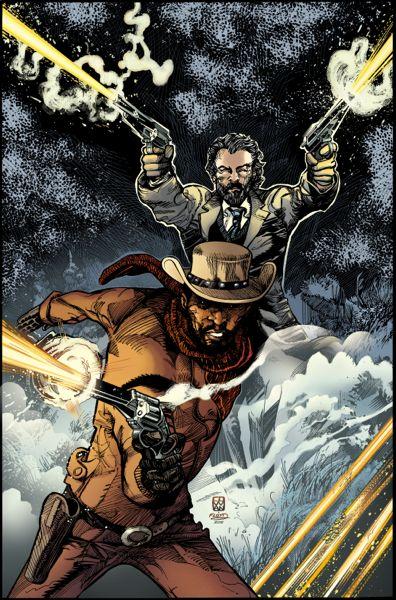

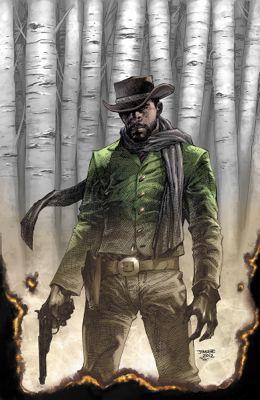

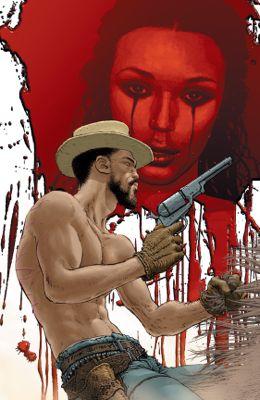

But fans of that original version will still have a chance to check out what it might have looked like visually, since Tarantino’s script has been adapted into a comic book series by Vertigo/DC Entertainment. The first of six installments drops Dec. 19; the second, which features a cover by Denys Cowan revealed here for the first time, hits Jan. 30 (three and four go on sale in February and March). Think of the comic series as an alternate version — that happens to come out first.

"There’ll be a lot of scenes in the comic that are not in the finished film," says "Django" producer Reginald Hudlin, whose comic book credits include Marvel’s "Black Panther" and "Birth of a Nation." While putting the final touches on the film, Hudlin took some time to give Indiewire his first in-depth interview about it — plus his thoughts on black superheroes, nerding out with Tarantino and the challenge of translating a 168-page screenplay into panels and word balloons.

Who came up with the idea for a "Django Unchained" comic book?

It kind of happened organically, actually. We were getting proposals to publish an illustrated screenplay, meaning it would be the screenplay with a bunch of photographs from production, and Quentin didn’t really want to do that. He believes the screenplay is an artistic medium in itself. He loves publishing his screenplays, but he wants them to stand alone and not have pictures as a crutch; either the writing works or it doesn’t. And when Quentin gave me that response to the offer I said, "Well, I get that. And, in fact, I was kind of disappointed because when I read ‘illustrated screenplay,’ I thought they were talking about a comic book adaptation." Then he lit up, like, "Yeah. Now, that’s what I’m talking about! That would be fun." [laughs] I agreed, so I reached out to my friends in the world of comic-book publishing and we got it going.

Has a slave ever been the hero of a comic book?

There haven’t been many, but yes. I mean, I have a great appreciation for the medium and so does Quentin. His specialty is, in whatever you’re talking about — film, television, comic books — he will mention very obscure characters and titles. For example, we talked about comic books — specifically the subcategory of Western comic books — and how big a fan he was of "Gunhawks," which had a black slave who was teamed up with a Confederate soldier. To me, that’s typical Marvel. [laughs] Like, what’s the boldest, craziest combination we can put together? The fact is, as per usual, comic books are bold and will go to provocative places. I can also say, pretty confidently, that no one’s ever seen anything like "Django" before.

The plot for "Django" revolves around a newly freed slave in the antebellum South attempting to rescue his lost love, Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), who was sold to another plantation. Though slaves could not legally marry during that period, did Django and Broomhilda consider themselves husband and wife?

You’re asking the question we bring up in the movie. Schultz [Christoph Waltz’s character] tells Django, “I didn’t know slaves recognized the institution of marriage.” And Django says, “Me and my wife do.” I mean, at the end of the day, doesn’t it come down to that? Marriage is a state of mind. Plenty of marriages on paper mean absolutely nothing.

Speaking of things on paper that aren’t necessarily binding, the original “Django”script went through numerous changes during production, and I heard that the gang rape of Broomhilda was toned down considerably. Quentin decided to shoot it in a way that protected Kerry while still conveying that something horrible happened to her character. Were those changes a direct result of her conversations with you and Quentin?

Let me answer that by making a broader statement. Quentin writes these scripts, and obviously he’s one of the best writers we have in our business right now. As the crew, we tend to treat his scripts with great reverence, like, “let’s figure out how to execute this exactly as he wrote it.” Quentin, though, looks at the script very much as a living document. He’ll show up on set with some new dialogue written on lined paper that he’s ripped out of a notebook and give it to an actor and say, “Learn this.” [laughs] And we’re going, “WHAT?” Then we see what he’s doing and say, “Oh, my God.”

Because it’s so much better.

We were completely happy before. But Quentin is constantly trying to figure out how to elevate, and part of that is talking with his actors. He’s not necessarily trying to appease his actors. But they are his partners, and he listens to them for their emotional truth.

Can you give us an example?

There was a whole other scene that kind of kicks off the third act of the film. Quentin knew the scene worked for every character except one, Jamie’s character, and when we were rehearsing it, Jamie said, “Oh, I’d play it this other way.” Quentin said, “Oh, really? I didn’t think you’d do that.” Jamie said, “Definitely, I’d play it like this…” That previous concern Quentin had, combined with Jamie’s instincts, made Quentin rewrite the third act of the movie! He always wants things to be true. That’s why he shoots the movie in what he calls “emotional order,” meaning it’s not quite in continuity order. But his thinking is, here’s a big scene, and based on how that goes maybe I don’t need so much of this other stuff, or maybe I need more of something else. Those things happened throughout the process of making the film.

You and Quentin seem like a very unlikely team. How did you first meet?

We met years and years ago. I’m friends with Pam Grier, who invited my brother Warrington and I to an awards event where she was being honored for her work in “Jackie Brown.” Quentin was presenting the award. And as soon as we met, Quentin said, “I saw that special you did for HBO, ‘Cosmic Slop.’” Now, this is something very few people have seen. It’s an obscure part of my filmography. And Quentin goes, “I don’t know why you did that short ‘Space Traders’ [about aliens who offer to buy the African American population] for HBO. That’s a feature. You blew that!” I was like, whoa. Then I thought about it and said, yeah, you know, he’s kind of right. [laughs] That kind of started our relationship, where we would meet up whenever and talk very, very passionately about movies, about everything.

Do you ever get competitive with each other when it comes to pop minutiae?

“Competitive" is not the right term. It’s more like we “revel in our nerditude.” I remember overhearing my assistant describe our interaction to someone. He said, “Yeah, Reggie and Quentin will talk, and then they’ll just go to a place and no one knows what they’re talking about.”

Is there any talk of releasing Quentin’s earlier films, such as “Pulp Fiction,” as comic books?

Funny you should say that. When we were looking at the “Django” pages, we were lamenting that we hadn’t started this a lot sooner. And I said, “Well, maybe it’s not too late.” So, yes, that conversation has started. I think comic books are part of the complex strain of DNA that make up what people think is the Tarantino style of storytelling. You’ve got all kinds of things that go into that mix. And for someone like myself, who never understood why he never did anything in that medium, I was very excited to shepherd “Django”into the comic book format.

Tarantino’s scripts are extremely quotable and dialogue-heavy. How do you go about adapting one?

I was a little intimidated at first. But if you just break up the story into the appropriate number of panels, it actually flows really well. When I was showing Quentin the first 10 pages of the book, I said, “Look, we’ve got it all in there, and the page isn’t drowning in word balloons. You still have plenty of room for the art.

Can you talk about the decision to go with R.M. Guera for the book’s illustration, and what kind of direction Quentin gave him?

We looked at a lot of artists, and Quentin picked R.M. Guera, who has done great work but is best known for “Scalped,” which is a kind of noir series among Native Americans set on a reservation. He’s a brilliant artist, and that sensibility is perfect for what Quentin’s doing. Also, R.M. already worked with Quentin, adapting a couple of scenes from “Inglourious Basterds” for Playboy magazine. “Django” was that same approach: Don’t draw what’s in the movie ; draw what’s in the script, which in some ways is different from what’s in the movie. We also have a great lineup of different cover artists: Jim Lee, Denys Cowan, Alex Ross and Frank Quitely. They all do their interpretation of Django. I get excited about projects like this, because I also feel like it’s a way to help support a medium that means so much to me.

It’s been a while since the comics industry has seen a new iconic black superhero. Do you think “Django”has the stuff?

He could. I’m committed to the concept of black superheroes, no matter what. And I certainly consider Django a superhero.

The first commercial black superhero was “Black Panther,” which you helped revive in 2005.

That’s right. When I was writing “Black Panther” for Marvel, I told them I want to give back to that next generation, and the series turned out to be a huge success. “Black Panther” is the biggest seller in the Marvel Knights line of animated DVDs. It out-sold Joss Whedon’s “X-Men,” which is pretty amazing given the brand power of those two great names. It out-sold “Iron-Man Extremis.” BET, who reluctantly aired the series at midnight, keeps re-running it because it gets a huge ratings bump every time, without any marketing and promotion. The show has become this amazing cult hit. [Hudlin was BET’s president of entertainment from 2005 to 2008.] A lot of my interest in comic books is diversifying the audience base. One of the nicest compliments I ever got was from a comic book retailer who said, “Reggie, we love when your comic books come out because we get different people coming into the store.” By “different,” he didn’t just mean black, he meant not the same people who come in every Wednesday. When I go to a comic book signing, there are tons of women. I see adults and kids — Latin, Asian, white, black — and I think that’s healthy for the industry.

Are you still planning a big-screen version of “Black Panther?”

Yeah, but those decisions are up to Marvel. Certainly, Stan Lee [who created the character with artist Jack Kirby in 1966] has said on multiple occasions he wants a “Black Panther” movie to get made. People are constantly asking me, “What’s the holdup?”

And what’s going to happen to Django when the miniseries wraps up?

Don’t know. Of course, I want very much to see the further adventures of Django. Quentin and I have talked about what those might be. But I want to see it in a feature film, and I don’t want a comic book to pre-empt or put him off doing a sequel, even though Quentin’s [officially] never done a sequel in his life and may never do one. All I know is we’ve got a great movie coming out, and we’ve got a great comic book, and we’ll see what happens after that.

Craigh Barboza is a New York-based freelance writer. His work has appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Uptown, USA Weekend and Vibe.