Quentin Tarantino on Django Unchained and the Problem with Roots

How he’s shattering a genre with ‘Django Unchained’.

by Allison Samuels

Good friends can talk about anything, and for director Quentin Tarantino and producer/director Reginald Hudlin, anything usually included long, good-natured chats about the mechanics of the African-American slave trade.

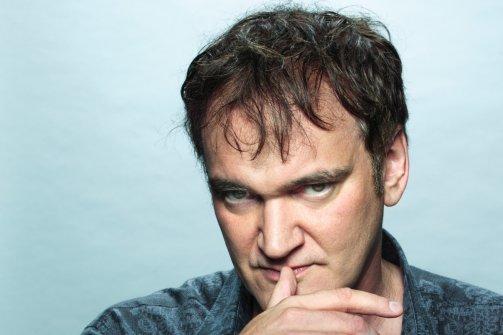

“The dynamics of the country are changing and people are talking about that,” says Tarantino… "I may take flak but I always do on some level with my work. Wouldn’t be a Tarantino film without some flak and criticism. I bet anyone who sees the film won’t be able to forget it—and that’s the point.” (Photograph by Jeff Minton for Newsweek)

The lack of a respectable film detailing the impact of slavery on this country fascinated both die-hard film buffs. Eventually both men—who met on the set of Jackie Brown in 1997—became obsessed with the idea of crafting a no-nonsense, somewhat entertaining film detailing the lesser known aspects of slavery. After one conversation with Hudlin stuck in his mind, Tarantino went to work on an all-or-nothing script. Six months later, Django Unchained was born.

Set in the South just two years before the Civil War, Django Unchained (in theaters Dec. 25) somehow masterfully manages to present the haunting brutality of slavery while also infusing an outlandish humor only Tarantino could bring to the big screen. Moviegoers will be treated to the often controversial director’s deep love for the spaghetti western genre along with a blazing narrative of one man’s desire for vengeance and love. After being freed by a German bounty hunter, Django (Jamie Foxx) helps him track down a few bad guys for profit and then goes on a mission to find and free his enslaved wife (Kerry Washington).

“I was always amazed so many Western films could get away with not dealing with slavery at all,” says Tarantino, sitting in Todd-AO studios in Los Angeles where he was attempting to whittle the film to under three hours just after Thanksgiving. “Hollywood didn’t want to deal with it because it was too ugly and too messy. But how can you ignore such a huge part of American history when telling a story in that time period? It made no sense.”

It didn’t make much sense to Hudlin either. The director of the popular ’90s films House Party and Boomerang says he was baffled by the sugarcoated and abbreviated tales. “I hated all those films about slavery over the years. Any time Hollywood did deem it OK to talk about slavery, they were not worth watching,” says Hudlin, who is Django Unchained’s executive producer. “My idea of a great slave movie was Spartacus. Until African-American slavery was treated in that same manner, I had no interest in hearing what Hollywood had to say about the issue.”

With only two years of age separating Tarantino and Hudlin, they watched the same slavery-themed films as young kids—and then grew to hate them as adults. Titles such as Mandingo and Uncle Tom’s Cabin roll off their tongues with joint eye rolls and audible sighs. The not able period film Glory, starring Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman as freed slaves serving in the U.S. Army, gets an honorable mention nod from Hudlin.

“I liked the black characters in Glory,” says Hudlin, whose great-grandfather was a conductor on the Underground Railroad. “Didn’t see the point of the white ones. The true story was the slaves in the film. They should have been the main focal point of the entire plot. But somehow no one figured that out.”

The faults of Glory aside, not much compares to the anger both men harbor toward the landmark television miniseries Roots. Written by Alex Haley and hailed in 1977 for telling the “complete” story of slavery, Roots remains the third most-watched miniseries of all time. It is also still considered the definitive mainstream portrait of slavery in the U.S.

“When you look at Roots, nothing about it rings true in the storytelling, and none of the performances ring true for me either,” says Tarantino. “I didn’t see it when it first came on, but when I did I couldn’t get over how oversimplified they made everything about that time. It didn’t move me because it claimed to be something it wasn’t.”

While many white directors might shy away from criticizing such an iconic symbol of African-American culture, Tarantino doesn’t hold back. He’s confident in his knowledge of a time and subject most people know little about and would rather forget. He was also savvy enough to bring Hudlin on board. “There were times when I’d be filming a scene and really getting into it and Reg would just say, ‘Hey is this the story you wanted to tell?’ He’d bring the focus back if I got too carried away.”

One thing both men agreed on was a scene in Roots that served as an example of what not to do in Django Unchained. The last act of the final episode features the character Chicken George being given the opportunity to beat his slave master and owner in much the same way he’d been punished and tormented. In the end the character chooses not to so he can be “the bigger man.”

With only two years of age separating Tarantino and Hudlin (left), they watched the same slavery-themed films as young kids—and then grew to hate them as adults.

“Bulls–t,” exclaim both Tarantino and Hudlin in unison as they discuss the absurdity of the scene. “No way he becomes the bigger man at that moment,” says Tarantino.

“The powers that be during the ’70s didn’t want to send the message of revenge to African-Americans. They didn’t want to give black people any ideas. But anyone knows that would never happen in that situation. And in Django Unchained we make that clear.”

Tarantino recalls a memorable scene where Jamie Foxx’s character is also given the opportunity to beat his former owner after he becomes a free man. “It was an emotional day on set and everyone was talking about how brutal it was because he beats the white off of his captor,” says Tarantino unapologetically. “There was no way that wasn’t going to be a part of the movie.”

Foxx shines as a man driven to punish those who tortured him, while also yearning for his wife, who was sold to another plantation years before. “It’s really important that this story is also a love story about a black man and a black woman,” says Hudlin. “In the midst of all the horrible things going on during that time, this man was in love and wanted his wife back. You don’t see black men in love too much on the big screen in slavery days, or modern times either.”

In a film already full of twists (not to mention costars Samuel L. Jackson and Christoph Waltz), Leonardo DiCaprio throws the ultimate punch portraying the young, handsome, rich plantation owner Calvin Candie. He owns Candyland plantation, where Django’s wife is being held, and thrives on the suffering he causes. The role is a marked departure for DiCaprio, who has spoken about how difficult the subject matter was to read, act, and convey on the big screen.

“He really embodied that entitled young male character perfectly,” says Tarantino. “His grandfather owned and made the plantation successful and his father kept it going in the movie. But DiCaprio’s character is just this kid who’s done nothing for the life he’s living. He’s living it up all the way with his decadence and greed, with no concern for how he got it.”

But neither an A-list cast nor Tarantino’s past box office hits will be enough to save Django Unchained if moviegoers decide not to support a film that focuses so intensely on one of America’s darkest hours. Slavery is a subject both black and white audiences tend to avoid in theaters. Yet Tarantino and Hudlin say the timing for Django Unchained couldn’t be better.

“The dynamics of the country are changing and people are talking about that,” says Tarantino. “This time in history is a part of that conversation, and I love that we’re out there talking about it in the middle of the other films about Lincoln and whoever. I may take flak but I always do on some level with my work. Wouldn’t be a Tarantino film without some flak and criticism. I bet anyone who sees the film won’t be able to forget it—and that’s the point.”