REGGIE HUDLIN APPEARS IN THE NEW YORK TIMES REVIEW OF BOOKS!

The Harlem Renaissance Through Zora Neale Hurston’s Eyes

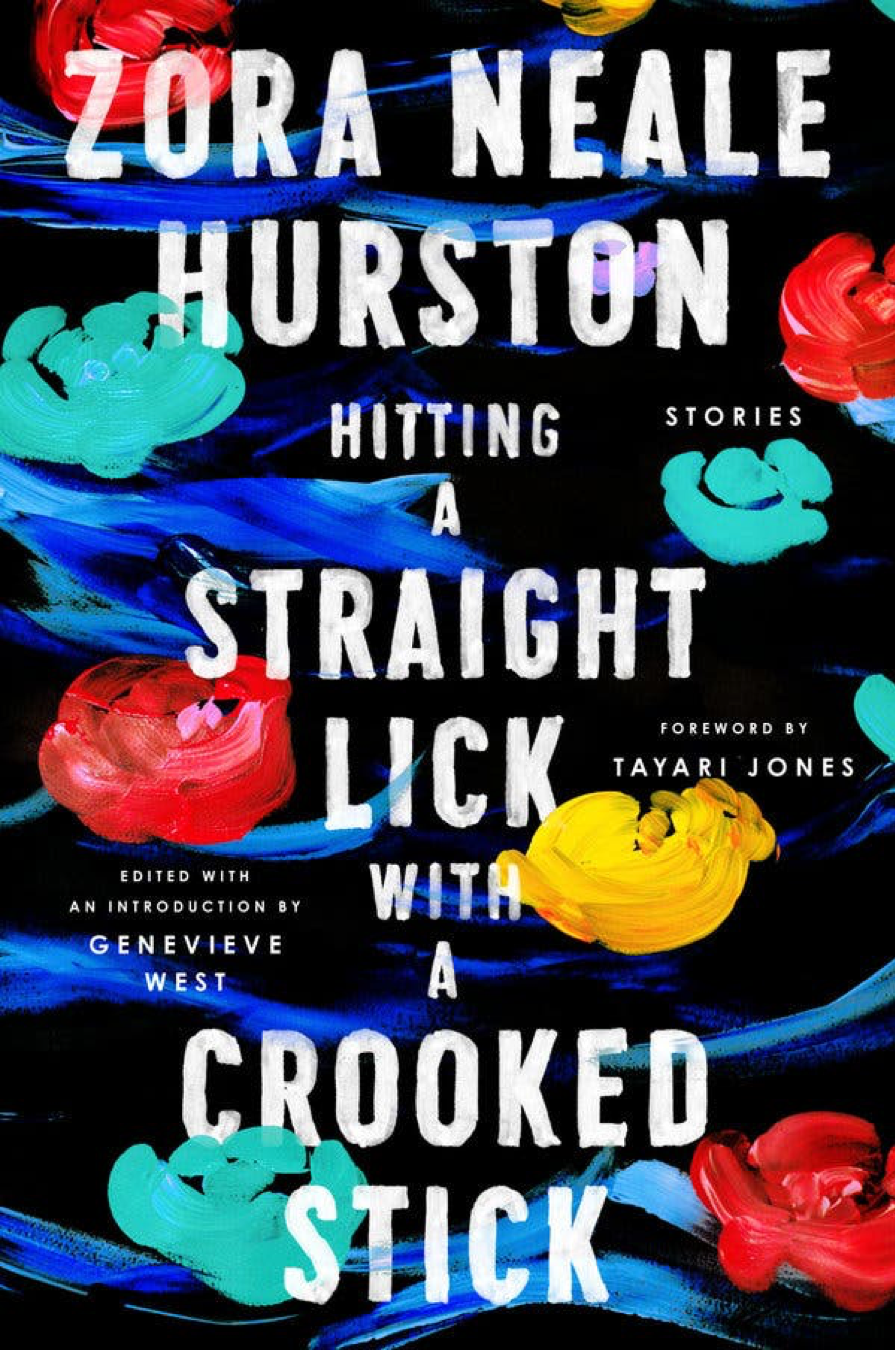

HITTING A STRAIGHT LICK WITH A CROOKED STICK

Stories From the Harlem Renaissance

By Zora Neale Hurston

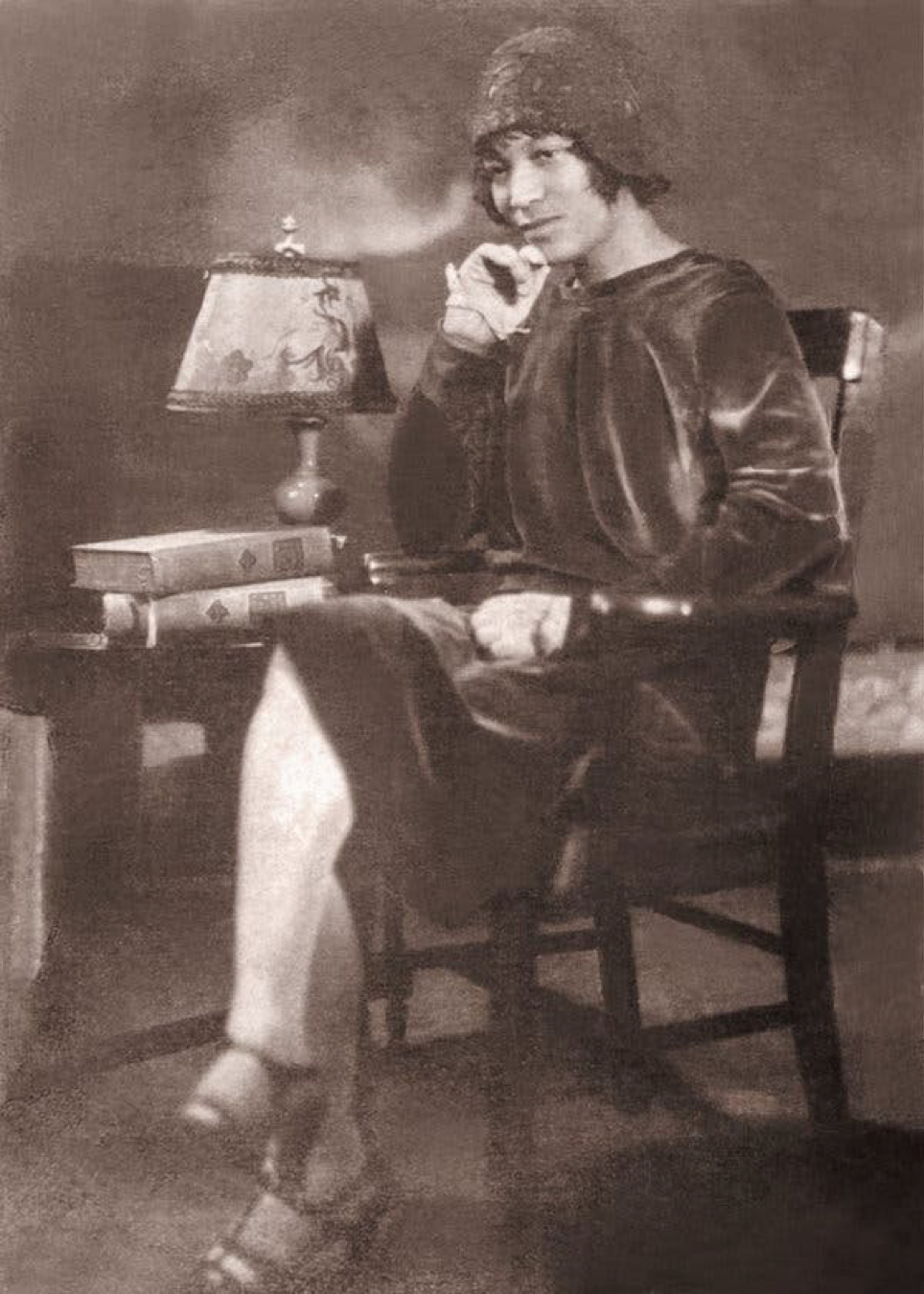

Early in Reginald Hudlin’s 2017 biopic about Thurgood Marshall, Zora Neale Hurston makes a memorable cameo appearance. The soon-to-be legendary attorney and his wife are sharing a booth at a nightclub with Langston Hughes and a friend when Hurston saunters in. Portrayed by the R&B star Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas, she looks as if she’s stepped out of a Carl Van Vechten portrait, oozing confidence and sly intelligence. The brief scene in “Marshall,” with its cutting repartee, suggests what Hurston admirers have long known: She would have been some kind of star even if she’d never parked her genius in front of a typewriter. But how fortunate we are that she did. Today she is revered as a peerless raconteur, intrepid investigator of culture and ritual, and author of a great American novel, “Their Eyes Were Watching God.”

“Hitting a Straight Lick With a Crooked Stick,” edited and with an introduction by Genevieve West, with a foreword by Tayari Jones, helps illuminate Hurston’s path to iconic status. Its 21 stories are presented in the order in which she composed them. As a result, readers can note the progression from earnest “apprentice” works and experiments with form to the polished brilliance of her best-known stories. The latter include “The Gilded Six-Bits,” with its plot turning on heartbreak and betrayal; “Spunk,” a spooky adultery fable drenched in swagger; and “Sweat,” a nail-biting tale of domestic terror.

West is primarily interested in the eight “recovered” stories that unfold in Northern places like Harlem. She notes that their settings, far from Hurston’s well-known Eatonville, Fla., locale, “reflect the tumult of the Great Migration,” expanding our understanding of Hurston’s fictional territory. She also points out that stories like “The Book of Harlem” differed from Hurston’s fellow writers’ treatments of the epic journey from South to North by persistently flashing elements of wit. Just as Ralph Ellison sought to wring the marvelous from the terrible, Hurston boldly found humor in the midst of tragedy and disruption. All the while, she recognized that what a black audience found comic could be a double-edged blade, easily confusing uninformed audiences. (At the end of the intense “Six-Bits,” Hurston shows a white character blithely assessing what he believes to be the typical black personality: “Wisht I could be like those darkies. Laughin’ all the time. Nothin’ worries ’em.”)

Explaining the meaning of Hurston’s homespun title, West cites Hurston’s various definitions of the expression. Of those, my favorite is “making a way out of no-way.” Equally a part of Northern, Midwestern and Southern African-American culture, the saying recognizes our ancestors’ ability to survive and thrive in the most challenging circumstances. In many of the stories in this collection, Hurston’s men and women confront those challenges while also trying and failing at love, then trying again.

Hurston is equally insistent on displaying the bruised, bloody underside of romantic misadventure. “Everybody in the country cut the fool over husbands and wives — violence was the rule,” she writes in “The Country in the Woman.” Men aren’t the only ones who provoke mayhem, but they flaunt their willingness to live by their fists. And meat-axes. And pistols. (West calls this behavior “tyrannical masculinity”; she does not exaggerate.) Hurston’s willingness to show warts and wounds ran counter to black bourgeois sensitivities about revealing dirty laundry in public. Against the backdrop of Harlem Renaissance bigwigs calling for positive depictions of high-achieving Negroes, Hurston unpacked the lives of everyday black people doing everyday things.

Add her matchless powers of observation, exemplary fidelity to idiomatic speech and irresistible engagement with folklore, and the outcome is a collection of value to more than Hurston completists. Any addition to her awe-inspiring oeuvre should be met with open arms.