Reginald Hudlin Says Hardest Part Of Making ‘Sidney’ Was “Mourning” Every Sidney Poitier Story He Couldn’t Fit In – Contenders New York

Sean Piccoli | Deadline

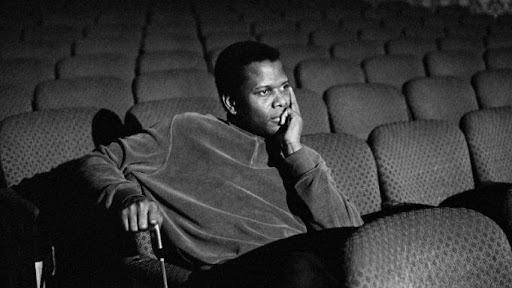

The challenge in making Sidney — about the pioneering Black actor, filmmaker and activist Sidney Poitier — was knowing where to stop, director Reginald Hudlin said during an appearance for Deadline’s Contenders Film: New York event at The Times Center in Manhattan.

“He had a long life, and every year of his life was consequential,” Hudlin said in a live video interview discussing the Apple Original Films documentary. “His teenage years were consequential. The circumstances of his birth were consequential. His retirement — he was an incredible mentor to an amazing range of people. So we wanted to get everything.”

“And honestly, there’s always a slight period of mourning after you finish a movie like this over the things you weren’t able to put in,” Hudlin said.

Poitier, who died in January at age 94, did not live to see the finished film, Hudlin said. But the anchor of Sidney is material from two days of interviews, previously unaired, that the Oscar winner did with the film’s producer, Oprah Winfrey.

Poitier talks about growing up on tiny Cat Island, in the Bahamas, without water and electricity; coming to America, and Harlem; learning to read, and copying diction from news broadcasts; and a career and life that, as he says in the film, had “more than a few wonderful, indescribable turns.”

“So we had eight hours of him telling his life story, and then we’re talking to everyone else,” Hudlin said. “Everybody’s got their favorite Sidney movie, their favorite Sidney story.” Hudlin offered his own on Saturday: “I remember catching two buses to go see Buck and the Preacher in a theater and spending all day there.”

With 1963’s Lilies in the Field, Poitier became the first Black actor to win a leading role Oscar. With his intense gaze and confident bearing, Poitier went on to play indelible characters in films such as Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) and In The Heat of the Night (1967) that challenged audiences to rethink the racial assumptions ordering much of American life.

Poitier’s barrier-breaking rise to movie stardom paralleled, and embodied, the aspirational arc of the civil rights era, and he didn’t shy from using his platform to lead by example and speak out. “There’s always those questions, do the times make the man or does the man make the time?” Hudlin said. “Because he was so self-made — literally — he knew how to reinvent himself, and he knew what to keep. And he was willing to risk it all.”

In an anecdote discussed in the film, Poitier and fellow actor Harry Belafonte drove through the heart of the segregated South to deliver money to racial justice organizers — and were nearly run off the road by a following car.

“That’s the absurdity of being Black in America,” Hudlin said. “There are so many stories like that, where Black Americans achieve extraordinary success and at the same time have to face the most mundane and pathetic forms of racism.”

Along with peers such as Robert Redford and Barbra Streisand, Sidney features interviews with African-American film royalty including Spike Lee, Halle Berry, Denzel Washington and Oprah Winfrey — a producer of the documentary — who credit Poitier with blazing a trail to Hollywood that they could follow.

Hudlin, director of House Party (1990) and Boomerang (1992) and a former BET executive, also worked with Poitier’s widow, actress Joanna Shimkus Poitier and daughter Anika Poitier, a director herself, to bring Sidney to viewers, and he said they agreed it should not be a “puff piece” that would gloss over some of the conflicts and disagreements he lived through, including a rift with younger Black audiences that began to regard him as a “sellout.”

“So the fact that his family has embraced the film and loved it and laughed and cried, and told me how much their father would love it — means the world to me,” Hudlin said. “And that since then, so many people who knew Sidney — and there’s so many people who know Sidney — they emailed me and called me and texted me and said, ‘That’s the man I knew. That’s the man I loved.’ So that validation from people who know his truth means the world to me.”

Check out the panel video above.