RIP TO THE GREAT MICHAEL KOSKOFF

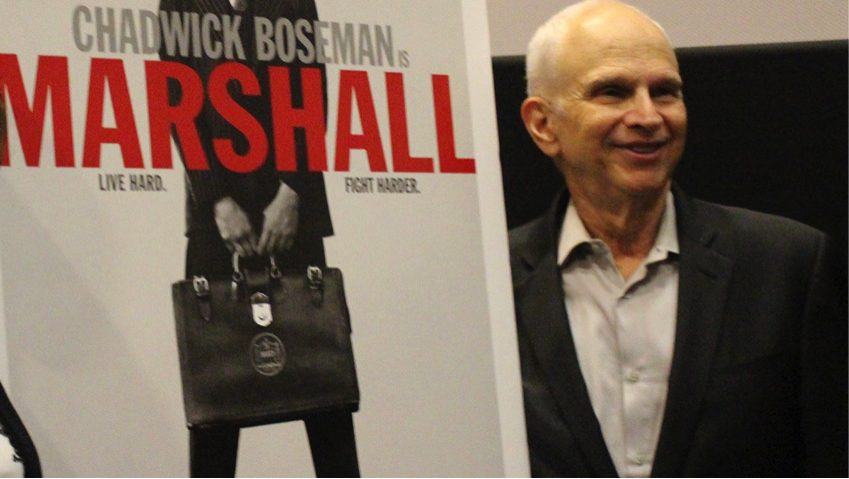

Michael Koskoff and his son Jake wrote the screenplay for my movie, MARSHALL. Please read the New York Times Obit printed below to truly appreciate what an amazing man he was.

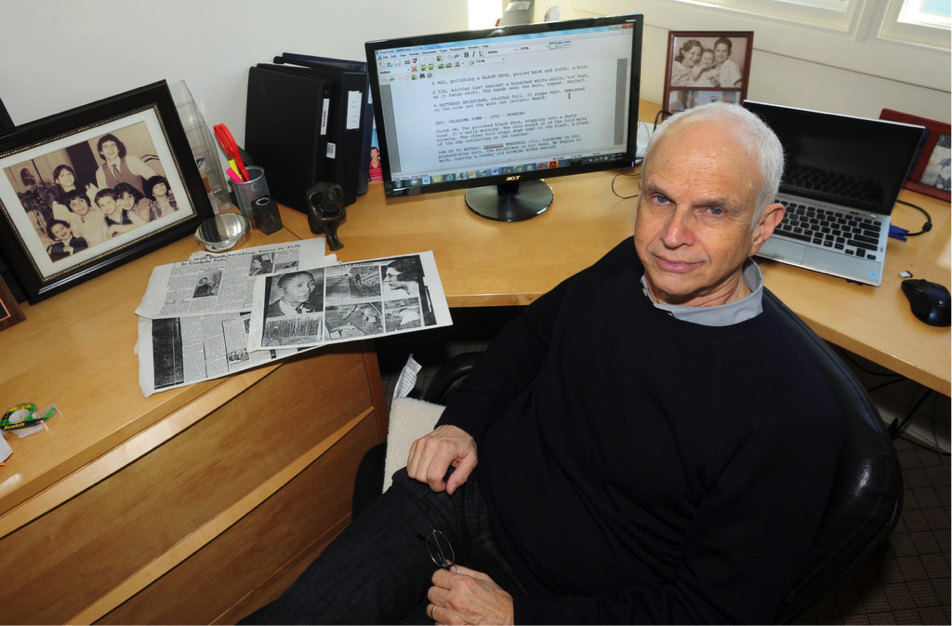

While he was a successful trial lawyer, his kids were into show business. So he decided he would write a script. He knew Thurgood Marshall had a significant case in his town, so he researched it and with the help of his son, wrote an amazing script that actually got produced! It’s a miracle of a story but when you read his life story it’s not surprising.

Mike was always a joy to be around. Always happy, hard working and always with his wonderful wife. I’m grateful to say he was my friend.

The lawyer Michael Koskoff in 2016 at his home in Westport, Conn. An author described his courtroom techniques as “raw theater.”

By Sam Robert – April 26, 2019

Michael P. Koskoff, a renowned and dogged Connecticut litigator who defended Black Panthers, won record malpractice awards, mounted racial job-discrimination battles and sued gunmakers whose weapons were used in the Sandy Hook school massacre, died on Wednesday in a Manhattan hospital. He was 77.

The cause was complications of pancreatic cancer, his son Jacob, a screenwriter, said. He and his father collaborated on the screenplay for “Marshall” (2017), a feature film about the 1941 trial of a black man accused of raping a white woman. The defendant was represented by a future Supreme Court justice, Thurgood Marshall.

Michael Koskoff advised his other son, Joshua, a senior partner in the Connecticut firm of Koskoff Koskoff & Bieder, in litigation against companies that manufactured and sold the semiautomatic rifle used by the gunman in the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012.

Last month, the Connecticut Supreme Court created a potential opening for victims’ families to hold the companies — including Remington Arms, which made the rifle — liable for the attack.

Mr. Koskoff, who lived in Westport, Conn., was the scion of a family of performers who starred on disparate stages. Some were actors, singers and musicians. (A cousin was Alfred Newman, the celebrated Hollywood composer.) Others were litigators who held forth in courtrooms. His father, Theodore, was both his law partner and a cellist.

“We’re show people,” Michael Koskoff once explained.

Mr. Koskoff won record settlements in Connecticut negligence and malpractice cases by coupling skills he had acquired in training to be a Shakespearean actor with a lifelong antagonism toward corporate greed.

He also pioneered the use of vivid courtroom videos delivered in a documentary format.

In 1979, Mr. Koskoff persuaded a jury in Danbury, Conn., to award his client $1.8 million in a wrongful-death case — Connecticut’s first verdict of more than $1 million in such a suit.

In 1999, jurors awarded $27 million for what he had demonstrated was a bungled heart operation at Yale-New Haven Hospital, which left a 29-year-old man permanently blind and brain-damaged. At the time, it was the biggest personal injury verdict in the state’s history.

That same year, Mr. Koskoff was lead counsel in a class-action case against the state for illegal wiretapping of calls between clients and their lawyers. It ended with a $17 million settlement.

In a medical malpractice case that became the subject of a book, “Damages: One Family’s Legal Struggles in the World of Medicine” (1998), by Barry Werth, a couple represented by Mr. Koskoff settled for $6.25 million in the early 1990s nine years after their baby, who had severe cerebral palsy and developmental disabilities, was born at Norwalk Hospital in Connecticut. (The child’s twin brother had been stillborn there).

Perri Klass, acknowledging that “while it may be difficult for a practicing physician like me to see a malpractice lawyer as a hero,” wrote in The New York Times Book Review that “Damages” did “full justice to Michael Koskoff’s skills, and to the mix of personal history, political fire and competitive zeal that sends him into court.”

In his book, Mr. Werth described Mr. Koskoff’s courtroom techniques as “raw theater.”

“Koskoff liked to depend on his own ‘visceral and instinctive reality’ of what was happening in a courtroom — was a witness nervous? arrogant? appealing? unappealing? — to decide how best to keep the drama fresh,” Mr. Werth wrote. “He also liked to keep the other side’s experts off balance by not letting them know what to expect of him. If he met them, he might like them, and that would dull his attack.”

Michael Peter Koskoff was born on March 19, 1942, in Bridgeport, Conn. His mother was Dorothy (Fuchs) Koskoff.

After graduating from the Cambridge School in Weston, Mass., he attended Brandeis University but left after a year to study at the American Shakespeare Academy in Stratford, Conn. Once he realized that he was unlikely to make a living on the stage (“Something about being a ‘bad actor’ deterred me from continuing,” he said), he enrolled in the University of Bridgeport. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English in 1963 and earned a law degree in 1966 from the University of Connecticut School of Law.

In 1963, Mr. Koskoff married Rosalind Jacobs, who survives him. In addition to their sons, he is also survived by their two daughters, Sarah Koskoff, an actress and screenwriter, and Juliet Koskoff, a lawyer in New York; two sisters, Elizabeth Koskoff and Susan Glazer; and eight grandsons.