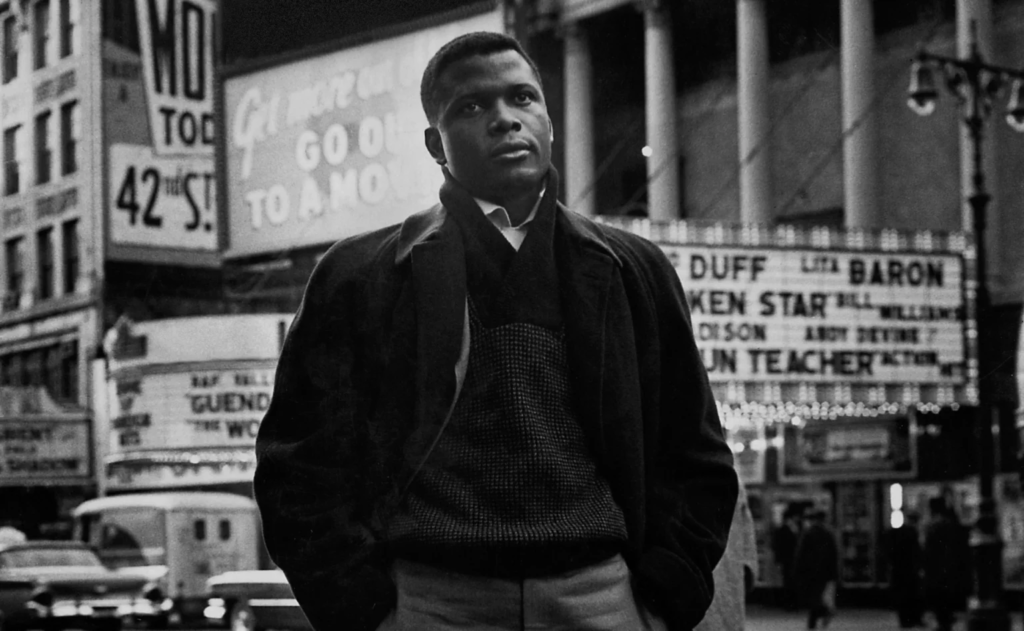

‘Sidney’ Review: Poitier Finally Gets the Documentary He Deserves

Christian Blauvelt | IndieWire

No one is better at telling Sidney Poitier’s story than Sidney Poitier himself.

The brilliance of Reginald Hudlin’s documentary for Apple TV+ is that it lets him do just that. An incredibly gifted storyteller, Poitier, who died at age 94 in January 2022, opens “Sidney” by saying in voiceover, “I was not expected to live.”

Of course we know that Poitier, who was born two months premature, his life hanging by a thread, did live, and lived exceptionally well, touching so many other lives with his groundbreaking Hollywood career. Having him tell his own story, largely via edited footage and voiceover from seven hours of interviews the film’s producer Oprah Winfrey conducted with Poitier in 2012, allows “Sidney” to be about the man, not just his milestones.

Many of the stories Poitier relates he’s told before in his books, especially his great 2000 memoir “The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography.” How, growing up without electricity on Cat Island in the Bahamas, he didn’t even see a car, or a mirror, until several years into his childhood. How, growing up in an environment in which he was surrounded by Black people, he didn’t think anything of the color of his skin. And how that all changed when he moved to the U.S. in his teens.

As powerful as those stories are on the page, they come to life that much more in his voiceover and direct-to-camera accounts in “Sidney.” Winfrey interviewed Poitier against a gray-black backdrop, with the camera zooming in at pivotal moments until his chin and the crown of his head touch the edges of the frame. Even then in his mid-80s, not having acted in more than a decade, he retained both his charisma and his commanding presence.

To both charm and lead: that’s what Poitier was able to pull off. There certainly had been powerful Black presences on screen before Poitier — Hudlin especially acknowledges Paul Robeson in the film — but there had not been a Black male lead in Hollywood who had two of the top 10 highest grossing films of a given year, as Poitier achieved in 1967 with “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” and “To Sir, with Love,” along with starring in that year’s best picture winner, “In the Heat of the Night.” After having become the first Black best actor winner (for “Lilies of the Field”) several years earlier, no less.

He had charmed audiences. Moviegoers handed over their money in droves to see him. As 1968 dawned, he was the industry’s number one box-office draw. But he also would lead — by being selective in the roles he chose so that he did not reinforce the stereotypes about Black lives that Hollywood had so often peddled. He eventually ended up behind the camera, populating the crews of the movies he directed with Black below-the-line talent, but even when he was just acting he brought a perspective and storytelling lens to interpreting his characters that anticipates him becoming a director.

What audiences did he charm, though? “His movies were not made for Black people,” says the late cultural critic Greg Tate at one point in the film. “Sidney” argues that his movies were trailblazing for acclimating white people to the humanity of Black people, a kind of cinematic desegregation that represented baby steps into a more diverse future. Yes, there’s Barbra Streisand, Spike Lee, Lenny Kravitz, Robert Redford, Morgan Freeman, Denzel Washington, and Winfrey herself appearing on-camera to sing Poitier’s praises, but Tate and a few other critics add a little more dimension.

Nelson George talks about how Black audiences didn’t buy into the famous moment of escaped convict Poitier jumping off the train to help Tony Curtis in “The Defiant Ones,” thus turning his back on his own freedom. He even suggests it’s a seminal moment in the history of the “Magical Negro” trope on film. A great montage set to James Brown and featuring clips from “Soul Train” and blaxploitation movies shows how quickly Black culture moved on from Poitier after his ’67 peak.

Poitier himself talks about his reaction to a New York Times article that asked “Why Do White Audiences Love Sidney Poitier So?” (Winfrey delivers one of the most moving moments in “Sidney” when she candidly says she could relate to this because of accusations that her talk show — or she herself — “wasn’t Black enough.”) His friend Harry Belafonte, with whom he fell out and reconnected several times over, implicitly criticizes the actor several times. And the film doesn’t shy away from telling the story of Poitier’s first wife Juanita Hardy, a Columbia graduate while he only had a grade-school education, and how their marriage ended because of his affair with the actress Diahann Carroll.

If there is some truth to the charge that his characters were overly perfect in order to be safe for white liberal audiences, Poitier himself does not come across as perfect here. Which only allows his humanity to reveal itself all the more. Likewise, his work behind the camera, for films like “Buck and the Preacher” and “Stir Crazy,” was not aesthetically groundbreaking (George flat out says “he’s not a great visual stylist”), but his work didn’t have to be revolutionary because he was revolutionary.

In “Sidney,” Hudlin has opted for a similar approach to Poitier’s own filmmaking: he’s not looking to shake up the documentary form, but the space he gives Poitier to tell his own story, and the compelling, cliche-free interviews with the “talking heads” on hand (95 percent of all the material here was filmed before his death), are so powerful that no extra intrusion of style is necessary.

Hudlin also knows how to tell a story. He’s directed the comedies “House Party,” “Boomerang,” and “The Great White Hype,” as well as the biopic “Marshall,” served as president of BET, and has had a side career writing graphic novels. His appearance on a 2016 ABC special called “Marvel’s Captain America: 75 Heroic Years” showed the range of his interests and the energy with which he can talk about them on-camera himself: “Why is he falling out a plane? I don’t know, just roll with it!” he shouted at one point, talking about a favorite panel of comic art. That enthusiasm for storytelling is all over “Sidney” as well. And so is a trust, on Hudlin’s behalf, that no extraordinary gimmicks are needed to give this story extra pop.

“Sidney” isn’t an encyclopedic account nor a film-by-film one. Your favorite Poitier movie may not even be featured (whither “The Slender Thread”?). It also sidesteps some problematic missteps (Preminger’s “Porgy and Bess” movie). But it makes you recognize, through the force of its telling, why the story of Poitier’s life matters. And will matter forever.

Grade: B+

“Sidney” is now streaming on AppleTV+.