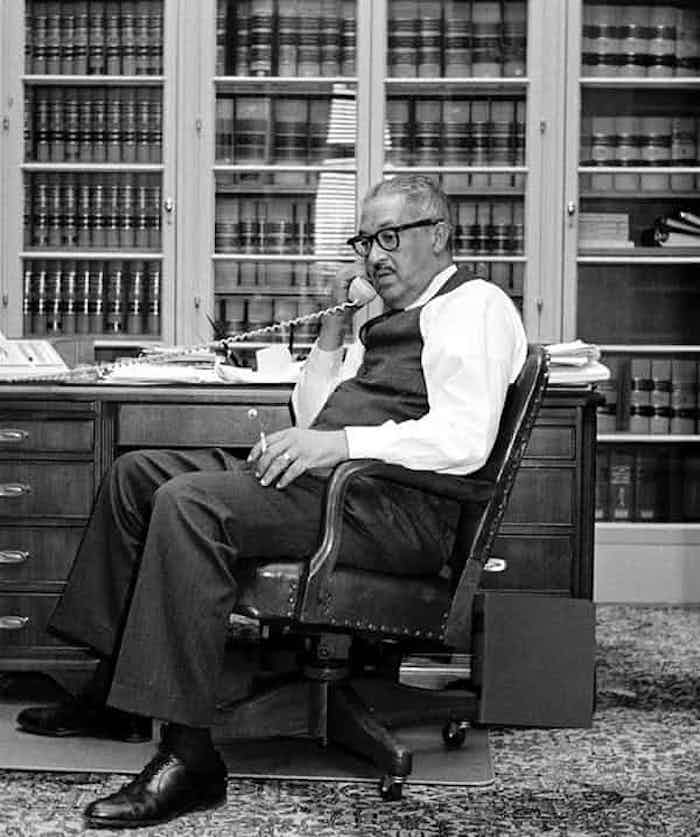

Thurgood Marshall: Activist, judge and the story of his quest for racial justice in America

The first African American to sit on the highest court is the subject of a film that retells his relentless and epochal quest to achieve racial justice in America

by Tom McCarthy

By the time the US supreme court banned the death penalty in cases of adult rape, in 1977, Thurgood Marshall had been a justice on the court for 10 years. He wrote a brief concurrence in the case, Coker v Georgia, citing his opposition to the death penalty, which then as now disproportionately targeted African American men.

Marshall’s experience with capital rape cases, and specifically with cases of black men accused of raping white women, was uniquely deep. For while the later decades of his career found Marshall enrobed as the country’s first African American supreme court justice, in his early years he had virtually lived from a suitcase, crossing the country as an activist lawyer known for defending innocent black men from a system of white justice that craved their freedom and their blood.

Of the 455 men executed for rape between 1930 and 1972, 405 were African American, Marshall had noted in a separate court decision. Were it not for him, the number would have been even higher.

As a lead lawyer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), beginning in the late 1930s, Marshall would leave his home in Harlem, get a train from Pennsylvania Station and ride for days into hostile territory:Oklahoma, Florida, Texas, Tennessee. His calling – and the NAACP was flooded with calls – was to defend against criminal charges and to represent plaintiffs in segregation, equal pay and voting rights cases.

In some criminal cases, Marshall might be able to win a life sentence instead of execution. In rare cases, he might win a not-guilty verdict. By the late 1940s, he was logging an estimated 50,000 miles a year, according to Gilbert King, whose Pulitzer-winning Devil in the Grove tells the story of Marshall’s defense of an infamous 1948 Florida rape case.

“The places he was going were places where there weren’t any other lawyers who were going to do this work,” said Kenneth W. Mack, a Harvard Law School professor who wrote Representing the Race: the Creation of the Civil Rights Lawyer. “They were also places where almost nobody had ever seen a black lawyer before. And he had to do things like challenge the local practices of segregation, come into a courtroom, call white people as witnesses, cross-examine them.

“He had to do things that, if he did them outside of court, it would have gotten him killed.”

As a pantheonic civil rights figure, Marshall is best remembered for arguing Brown v Board of Education (1954), which struck a decisive blow against racial segregation in public schools, and for his later, historic ascent to the bench itself. Those towering achievements have mostly obscured his dramatic early years.

But the popular portrait of Marshall may be about to shift, with the release next week of a new film, Marshall, which tells the story of a salacious 1941 rape case in high-society Connecticut and of Marshall’s intervention at age 32 on behalf of the defendant, a butler-chauffeur named Joseph Spell.

While Hollywood has taken cracks at supreme court biopics before, going back to Oliver Wendell Holmes in The Magnificent Yankee (1950), Marshall promises a more visceral excitement. The film unites the producer of Django Unchained (Reginald Hudlin, directing this time) with the star of the upcoming Black Panther Marvel Comics blockbuster (Chadwick Boseman). In Marshall, the young lawyer who will become the old justice not only batters his intellectual inferiors in court – he also strikes the bar with a bat and throws punches in a bar.

“The thing about Thurgood Marshall is his whole life is incredible,” Hudlin said, in a phone interview. “What intrigued me was this figure of him as a young man – vital, dashing, with this swagger – very different from the mental picture that you may have of him. I think he’s one of the most underrated heroes in American history.”

Hudlin, the director of House Party, Boomerang and The Ladies Man, is good at superhero stories, with a series of Black Panther graphic novels to his credit and a comics-inspired movie, Shadowman, in the works. But to hear historians tell it, his portrayal of Marshall as a kind of peerless crusader, striding the planet to achieve racial justice and salvage the soul of the nation, is more or less true-to-life.

“There’s nobody like Marshall,” said Mack. “If you needed a lawyer and you were being railroaded, he is often your last and only resort. And what he did took an incredible amount of courage. In all those things I think the movie is accurate, and people ought to see it, because they ought to remember Marshall. And I think the movie does a great job of remembering and dramatizing that part of Marshall’s career and his importance.”

Daniel Sharfstein, a professor at Vanderbilt Law School who has written about the Spell case, said the only atypical element of it for Marshall was that he probably did not face a risk of being lynched in Connecticut, as he did when he traveled in the South.

“When Marshall had gone to Connecticut to help with the defense of Joseph Spell, one thing that his co-counsel would remember years later was a lunch that they had where Marshall says, ‘It’s just amazing to be in a place where I don’t have to fear for my life’,” Sharfstein said. “In so many of these places where Marshall went to defend an African American from all manner of unjust criminal charges, his life was in danger constantly.”

The Spell case was a tabloid bonanza. One night a couple of weeks before Christmas 1940, Eleanor Strubing, 33, of Greenwich, Connecticut, the daughter of an investment banker and wife of a Princeton-educated advertising executive, was found soaked and shivering on the side of a highway, near a reservoir in New York. Her chauffeur, Spell, had raped her repeatedly, she said, then driven her to the reservoir, thrown her in and stoned her.

Police claimed that Spell, 31, confessed to raping Strubing after a 16-hour interrogation. Spell told Marshall and his local co-counsel, Samuel Friedman, that he had admitted to having consensual sex with Strubing in the car, but not to rape. Then the pair had gone for a drive that ended when an agitated Strubing ran away from him, Spell said. There were no witnesses because Strubing’s husband was in Cincinnati, Ohio, on the night in question.

It was not a capital case but Spell faced 30 years in prison. Marshall advised him to decline a plea deal that would have required an admission of guilt. When the trial began in January 1941, pitting Friedman and Marshall against a prosecutor who described Spell as a “lust-mad Negro” who stalked his victim “like a panther”, the Bridgeport Herald branded it the “most sensational sex mystery in history”.

“With the Joseph Spell case, what’s amazing is it takes place in Connecticut,” said Sharfstein. “The prosecutor is the prosecutor for Greenwich, Connecticut. Yet when he opens his mouth to describe Spell to the jury, he engages in a level of race-baiting that could easily have taken place in Mississippi.

“And I think the Joseph Spell case – in many ways it’s a footnote in the history of NAACP’s struggle against segregation. But I think it’s a case that shows just how much the north was also governed by the logic of Jim Crow.”

Hudlin said: “This is a classic tabloid case. There’s sex, there’s violence, there’s all this racial tension. There’s all the things that make TMZ and the whole tabloid culture that we’re currently in a success. That same culture existed in the 1940s. Everything about the movie resonates with our culture today.”

During the trial Marshall sat to one side, listening to his white colleague speak to the all-white jury, the same way he would listen more than 35 years later to lawyers trying to convince him and his fellow supreme court justices about rape and the death penalty. The stakes in Connecticut were high, but for once they were not life-and-death.

“I don’t use words like ‘superhero’,” said Mack. “But when I say he’s extraordinary, I include his intelligence, his sense of strategy, and his talent as just a brilliant trial lawyer.

“And it took a lot of courage. There was an ever-present threat of violence, by southern sheriffs or by white vigilantes. It wasn’t just the cases, it was also the travel, the things he had to do, the constant negotiation of Jim Crow and what could you say and not say, and what could you do and not do. And saying or doing the wrong thing could get you killed.

“In that sense Marshall really is extraordinary. It took an extraordinary amount of courage to do what he did.”