“WHO CAN’T GET ON BOARD WITH THAT?”: HOW ‘HOUSE PARTY’ BROUGHT THE BLACK TEENAGE EXPERIENCE TO THE MAINSTREAM

Released 30 years ago on Monday, the movie is best remembered for Kid ’n Play and an infamous dance battle. But the breakout hit was also one of the most important films of the 1990s.

“The fact is, these black kids are just like every other kid in America,” Reginald Hudlin says. “It’s the same drama, which is why everybody relates to the movie: It’s the universal experience of being a teenager.”

House Party—the first movie Hudlin wrote and directed—isn’t a novel concept. A teen from Anywhere, USA, gets in trouble at school and is forbidden by his strict father from going to a friend’s party, an order he obviously disregards. From there, the kid spends nearly 100 minutes trying to avoid ass-kickings from three muscle-bound tormentors, two racist cops, and one pissed-off father, all while hedging his bet with two girls who have varying degrees of interest in him. But despite the simple formula, House Party stands in stark contrast to many of the teen films that preceded it—because, as Hudlin mentioned, these kids were black.

The teen movies of the 1980s, such as those written and directed by John Hughes, left an indelible mark on the decade. In many ways, Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, Weird Science, Pretty in Pink, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off are as representative of the ’80s as Reaganomics. That is the snapshot of Americana his administration sought to protect. These films depict a distinctly safe, white, suburban teenage existence. Black teens of that era, on the other hand, had no quintessential equivalent. There were films targeting young black audiences that attained cult status, but they didn’t receive the same adoration. House Party, which was released on March 9, 1990, changed that. “Even though you had Beat Street and Wild Style, there was nothing like this,” says Christopher “Play” Martin, who portrayed the party’s suave host. Clueless sparked a teen movie revival during the mid-’90s and Cruel Intentions supposedly put the genre 6 feet deep at the decade’s close, but House Party set the standard.

House Party was the first teen movie released in the ’90s. It came amid new interest in black stories and black filmmakers, spurred by Spike Lee’s polemical Do the Right Thing the previous year; Keenen Ivory Wayans’s blaxploitation sendup, I’m Gonna Git You Sucka, in 1988; Robert Townsend’s Hollywood satire Hollywood Shuffle in 1987; and Lee’s first feature, She’s Gotta Have It, in 1986. The headline for a New York Times piece that ran just days before House Party hit theaters proclaimed, “In Hollywood, Black Is In.” Despite how Hollywood might have viewed black cinema, it wasn’t a mere trend. House Party was about to prove there was potency in putting black people in the center of a universal experience.

“Nowhere in that movie is a city or town mentioned because [Reggie] didn’t want anyone who watched it to feel like, ‘This could only happen in Chicago, New York, or wherever,’” says Martin. “If you tell the story right, who can’t get on board with that?” says Christopher “Kid” Reid, who played the lead role. Many people got on board, as a matter of fact: House Party became a box office surprise, raking in over $26 million on a $2.5 million budget. It helped turn New Line Cinema, then a relatively small company, into a reputable studio. It also significantly elevated its rookie director and some of its cast, many of whom were appearing in their first film, to stardom. Kid ’n Play. Full Force. Tisha Campbell. Martin Lawrence. AJ Johnson. Daryl “Chill” Mitchell. The late Robin Harris, who died of a heart attack at age 36 about a week after the film’s release, and the late John Witherspoon. And because House Party was about kids who loved hip-hop and featured hip-hop acts prominently, its success also helped ease hip-hop into the mainstream.

House Party isn’t just one of the most important black films ever made—it’s one of the most important films of the late 20th century, a movie that showed Hollywood the breadth of the black experience, and the immense interest in it.

Long before House Party became a classic, it was a student film of Hudlin’s. An undergrad at Harvard University in the early ’80s, Hudlin spent an entire summer working to fund his senior thesis project. On the last day of his break, he was packing up to return to school when Luther Vandross’s 1982 hit “Bad Boy/Having a Party” began playing on the radio. “At the time, black music videos weren’t really a thing, so I would come up with a music video in my head to a song,” Hudlin says. “I kept thinking about what that would be, and then I thought: ‘No, that’s a movie.’” He had spent the entire summer working on an unrelated script, but “Bad Boy/Having a Party” convinced him to rip it up and start on what would become House Party, inspired loosely by his upbringing in East St. Louis, Illinois. With the assistance of his older brother, producer and director Warrington Hudlin, he got the 20-minute version of House Party in front of more eyes.

The elder Hudlin, who served as a producer for House Party, founded the Black Filmmaker Foundation in 1978 with Yale University classmates Alric Nembhard and George Cunningham. The organization, which distributed early films by directors including Lee and Julie Dash, held screenings each summer where the younger Hudlin showed his short films, including House Party. The film soon found its way into the orbit of Janet Grillo, then a junior executive for New Line. “One of my staffers, Helena Echegoyen, was friends with Reggie, so she brought the short film he’d made as a Harvard undergraduate that was the short of House Party,” says Grillo, now a filmmaker and film professor at New York University. “I was very impressed. The talent just jumped off the screen and it was also personal. He came in to meet and actually had a very long treatment or rough first draft of a completely different script that was about a teenage band. We sort of played around with that for a couple of weeks and it just wasn’t happening, so I said, ‘Well, why don’t you just make House Party as a feature?’”

“One executive was like, ‘You know what no one wants to see? Black movies or teen movies. You have a black, teen movie.’”

Reginald Hudlin

According to Hudlin, they moved forward with New Line Cinema around 1988 because every other studio turned them down, citing the scope of the project. “I remember one executive was like, ‘You know what no one wants to see? Black movies or teen movies. You have a black, teen movie.’” Grillo, though, was keenly aware of the obstacles marginalized people face in Hollywood. “As someone who wasn’t able to create my stories because nobody gave a hoot about women telling stories until the last 10 years, I well understood the importance, necessity, and difficulty for people who are not mainstream, white, male, and heterosexual to get access to storytelling,” she explains. It was highly unlikely that Grillo would be able to secure distribution money for a first-time black director, but she pledged to develop the script with Hudlin and ultimately pitch it to her superiors—which she did, as a “black John Hughes film.”

At the time, the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise was New Line Cinema’s most successful venture. Those films changed the company’s trajectory, though even as the studio forced its way into the mainstream, the studio continued to target the sort of niche projects on which it found its success. New Line was looking for new ways to best accommodate underserved audiences, Grillo says, and House Party was it. The film had an earnestness similar to that of the 1975 blaxploitation-era classic Cooley High, minus the tragedy. “I said this was a different way to reach our audience,” says Grillo. “We’ve been looking at gangster films, we’ve been looking at obviously horror movies, but this is a totally different way to serve them—and it’s fresh.”

Hudlin, who was a fan of American Graffiti, National Lampoon’s Animal House, and Risky Business, admired Hughes’s films, but wanted to show the world black America’s version. “It wasn’t so much, ‘Oh, where’s the black character in those movies?’ I just thought, ‘We have those experiences too,’” he says. “My whole career has been focused on showing sides of black life that aren’t normally seen. I was really interested in doing something different and, at the time, there were a lot of very explicitly political films being made. Which is great, but I thought the best way to say something political is to do it in a way that doesn’t feel like you’re sending a message at all.”

Hip-hop was written into House Party’s script, but it went over the heads of many studio executives. Although the genre was rising in popularity during the late ’80s, and hip-hop-centric films like 1983’s Wild Style, 1984’s Beat Street, and 1985’s Krush Groove had become cult favorites, it still wasn’t on the average exec’s radar. Grillo says the staff at New Line’s New York office was well aware of hip-hop’s rising influence because they rode the subways and walked the streets, unlike their Los Angeles counterparts. “They were going from their houses, to their cars, to their screening rooms, to their offices and back, so there was no real understanding of this emerging thrum of culture,” she says. To remedy this, Grillo sent a copy of House Party’s script along with a xeroxed copy of an article detailing the rise of hip-hop to New Line’s Los Angeles office. The gimmick worked, and in 1988, New Line officially agreed to fund the production of House Party.

When it came to casting the two best friends at the center of the movie, New Line had its eyes on two budding stars, Will Smith and DJ Jazzy Jeff—because of their popularity and the fact that New Line had them in a legal bind over an uncleared sample. “When [Smith] was The Fresh Prince, he made this song, ‘A Nightmare on My Street,’” Grillo recalls. “He failed to get the rights from us for that. In the lawsuit, we gave him the option: Either you pay us money or you appear in one of our movies.” Hudlin, however, didn’t want Smith simply because he’d lost a lawsuit. “I don’t want him to not be into it, I only want him to do it because he likes it,” he remembers.

“I remember reading the original script, and we had been approached before by people trying to do movies with us, but this was the best thing I’d read.”

Christopher Reid (Kid)

In the late ’80s, Hudlin had directed videos for Uptown Records (original home of both Jodeci and Mary J. Blige) artists such as Heavy D and the Boyz. Through Uptown founder Andre Harrell, he came across the New York–based hip-hop trio Groove B. Chill (Daryl “Chill” Mitchell, Gene “Groove” Allen, and Belal “DJ Belal” Miller), whom he considered for top billing. “They saw me and Groove always cutting up, so they realized we had character,” says Mitchell of the Hudlin brothers. Mitchell adds that certain elements of the story—Lawrence’s character, also a DJ, being named “Bilal” after DJ Belal; being late to pick up the irritable Bilal for the party and damaging his equipment in the process; Belal yelling at Chill for bumping the table while he’s DJing—are based on some of their real-life experiences. However, New Line wanted more star power, though Groove B. Chill still appeared in the film. “They explained the scenario—they had to get a bigger name to get the movie made,” says Mitchell. “And that’s when they got Kid ’n Play.”

By 1989, Kid ’n Play’s debut album, 2 Hype, was certified gold and the duo, Christopher Reid and Christopher Martin, had a hit single with “Rollin With Kid ’n Play.” Hudlin came across their videos on the New York–based television show Video Music Box, which earned acclaim for its early embrace of hip-hop culture, and was impressed by their style, charm, and dancing ability. After meeting Reid in a New York City club and bumping into him a few more times, Hudlin eventually got him to read the script. “It was kind of my job in the crew to read stuff,” says Reid. “I remember reading the original script, and we had been approached before by people trying to do movies with us, but this was the best thing I’d read.” Kid ’n Play had booked a tour and stood to lose money if they opted to do the movie, fueling apprehension from an already uninterested Martin. “When you’ve got rap kingpins like Run-DMC doing a movie that a lot of people don’t remember or know like Tougher Than Leather, I was like, ‘If those guys can’t do a movie, then who are we to think we could achieve such a thing?’” says Martin.

But Martin was outvoted—Reid was in, and so was their manager Hurby “Luv Bug” Azor. “To this day, I’m glad that’s an argument that I lost,” Martin admits.

House Party was filmed over the course of 30 days in Los Angeles in 1989. Most of the cast was green. Campbell—whom Hudlin loved in 1986’s Little Shop of Horrors and 1988’s School Daze and who was cast as Sidney (the girl Kid ends up with)—was probably the most experienced. “Whatever technical question you had, she had the answer,” Mitchell remembers. AJ Johnson was cast as Sharane, who spends the bulk of House Party stringing Kid along, because she and Campbell were already friends. “That girlfriend energy just felt really right,” Hudlin says of their chemistry. Lawrence, who appeared in What’s Happening Now!! and had a small role in Do the Right Thing, also impressed Hudlin through his stand-up comedy. Watching stand-up also led Hudlin to Harris (whom he’d honor by writing and co-producing 1992’s Bébé’s Kids, which is based on one of Harris’s best-known comedy routines), who also appeared in Do the Right Thing and stole every scene with his legendary shit-talking. Hudlin dismissed objections to casting Harris. “People were like, ‘Oh, you can’t cast him because people can’t understand what he’s saying,’” he says. “‘Oh, you’re saying his accent is too black? Oh hell yeah, we’re casting him!’”

John Witherspoon, already a legend in Hudlin’s eyes, was cast off his work in I’m Gonna Git You Sucka, Hollywood Shuffle, and The Richard Pryor Show. And Hudlin, a huge Parliament-Funkadelic fan, wrote a role specifically for George Clinton—the funk deity has a cameo as a fast-talking DJ at a bougie affair—so he might have the chance to meet him. Full Force, who were already known for their own music as well as writing and producing for Kurtis Blow and Lisa Lisa and Cult Jam, wound up in House Party as the bullies because the script already included descriptions of them. “It said something like, They get accosted by three bullies with great physiques and Jheri curls, somebody like Full Force,” says singer Lou “Bowlegged Lou” George, who played Pee-Wee.

Full Force completely rewrote their characters’ dialogue (adding their catchphrases, of course) so they didn’t come across like the archetypal bullies Brian “B-Fine” George and Paul “Paul Anthony” George played in Krush Groove. “I said look, if [the Hudlin brothers] don’t like it, I’ll go back to the original script—as boring and bland as it may be,” George remembers, explaining how he improvised to make the trio feel three-dimensional. “And as soon as they saw us do it, they gave us the thumbs up.” Hudlin gave the rest of the cast similar latitude. “To Reggie’s credit, he was like, ‘We just gotta get there. It doesn’t matter how we get there, but I want to get there in your voice,’” Reid says.

Unsurprisingly, giving Harris carte blanche unleashed his trademark brazen, acid-tongued humor. “We were using tape and not digital, so you couldn’t be wasting film, and Reggie and them would say ‘Action!’ and tell [the camera people] don’t roll the camera because they knew we were gonna laugh when we weren’t supposed to because Robin Harris would keep coming up with something different each time,” says Mitchell. “He’d have the dude holding the boom mic laughing and then the boom would dip into the shot,” Reid adds with a laugh. The comedy didn’t stop with Harris. “Martin Lawrence was hilarious, he used to make fun of Kid ’n Play,” George says. “His favorite Full Force song was ‘Temporary Love Thing’ and he’d start singing it on set.” That atmosphere made it easier to film some of the more labor-intensive scenes, such as House Party’s most famous offering: the dance-off.

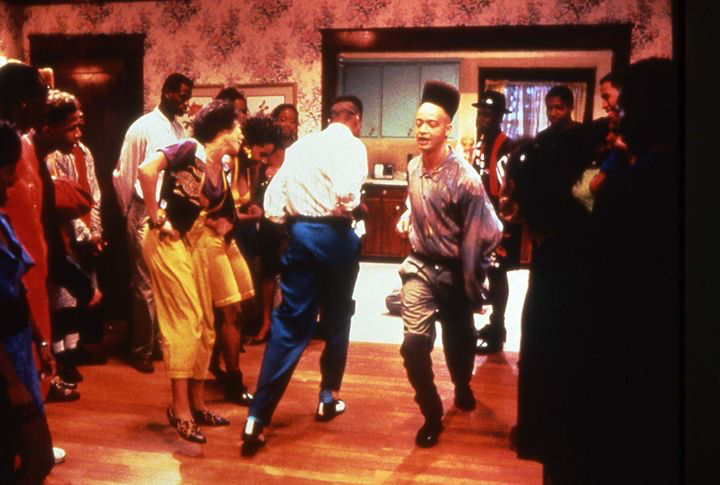

What began with Chill pressing Kid to show him a particular maneuver turned into the scene that defined the entire movie. It’s impromptu, transitioning quickly from a sequestered kitchen exchange to the heart of the party. The scene pits Kid ’n Play’s brash, free-form style against Campbell and Johnson’s fluid, Soul Train–esque method. “I think what we were able to accomplish was an abstract tribute to different forms of music,” says Martin. It was the product of intense choreography and sweat in a dance studio that, due to the cast and crew’s bond, never felt like a chore. “That was just a walk in the park for us,” says Reid, adding that those were moves they sharpened through live performance. “Those girls are awesome,” Reid says of Campbell and Johnson. “They’re my homegirls, but we smoked them.” (Neither Campbell nor Johnson could be reached for comment.) All parties brought their A-game, so the audience is the true winner.

As wonderfully random as the scene is, it’s the type of moment—a jolt of euphoria—a teenager would absolutely sneak out of the house for. Roger Ebert described House Party as “a musical” in his review, and Hudlin, a proud fan of the genre, still considers filming the scene a top-five day in his life, up there with the birth of his children. “I’ve come to realize that it’s like that Nicholas brothers scene from Stormy Weather or one of those Gene Kelly scenes from Singin’ in the Rain,” he says. “It’s one of the most famous dance scenes in a movie that has ever existed.” Reid agrees, adding that the payoff was more than worth the hours poured into making it: “It was one big, long day. But at the end of it, it’s like, ‘We got paid for that?!’”

It’s a fantastic musical cue in a film filled with them. There’s a perfect callback to the song that inspired House Party, “Bad Boy/Having a Party,” at the very beginning of the film. There’s the rap battle where Kid gets to shine, and for which Reid wrote both his and Martin’s lyrics (“Reggie used to tell me, ‘You’re supposed to win, but let’s get there in a certain way,’” he recalls). There’s the slow dance to Heatwave’s “Always and Forever.” There’s even Kid’s surreal jailhouse rap, which Hudlin now regrets for its homophobia (“There’s nothing worse than offending people who you don’t mean to offend,” he says). But what makes the dance-off stand out is the buoyant “Ain’t My Type of Hype.” The song, originally included on Full Force’s 1989 album, Smoove, blew up due to the movie. “The Hudlin brothers loved that song, and to this day, because of House Party, ‘Ain’t My Type of Hype’ is our most popular song ever,” says George.

Longevity wasn’t on anyone’s mind, even as the set drew notable visitors at random. “Laurence Fishburne was shooting Pee-wee’s Playhouse; he’d stop by,” says Mitchell. “We saw Sylvester Stallone—he popped his head in because we were doing it. To see him out there, it was like, ‘Damn, that’s Sly Stallone.’ So many actors would come by the set. Then when we did the wrap party, Denzel [Washington] came because it was a big deal.”

Still, no one involved with House Party realized the film was about to change their lives.

It took just one weekend at the box office for House Party to recoup its budget—and then some. House Party succeeded far beyond anyone’s expectations, and the response at early screenings revealed that the film was special. “A lot of movie makers of this type of film still look at House Party, business-wise, as a level to reach,” says Martin.

Most importantly, however, House Party repudiated Hollywood’s unfounded yet closely held belief that no one cared about black teen movies. “There was a screening on this lot of 20th Century Fox. We’re driving to the lot, and there was all this traffic, and we got nervous about being late to our own test screening because of it,” Hudlin says. “Then we realized the traffic was people coming to the test screening of House Party. We were causing a traffic jam.”

When the Hudlins took the film to the Sundance Film Festival, it debuted at midnight to a packed theater. Hudlin says that two people from the almost exclusively white crowd approached him afterward with praise. “One was Michael Moore, the filmmaker who did Roger & Me and all those movies, and he was like, ‘Man, I love this movie!’” he says. “And then there was an executive from Warner Bros. who was like, ‘I read your script. I didn’t get it, but I get it now. We’ll buy this movie from New Line. I love this movie.’”

Mitchell realized he was part of a phenomenon when the since-demolished Commack theater in Long Island, New York, sold out of tickets for House Party, which was showing in only one theater. “We got in there and I saw people sitting on the floor in the aisles,” he says. “Security was trying to get them to move and they’d just get up and go to another spot. Girls were sitting on dudes’ laps that they didn’t even know. And when we hit that screen, the noise that came out of that movie theater, yo, I was like, ‘Oh my God …’”

The widespread appeal of House Party became even clearer when the film was released on home video. “This guy who owned a video store in Orange County was like, ‘I can’t keep House Party on my shelf,’” says Hudlin. “‘Don’t let anyone tell you that white people aren’t watching this movie because my customers love it.’”

“It wasn’t just a black movie. I’m sure New Line thought it was—but it transcended that.”

Christopher Reid (Kid)

“It wasn’t just a black movie,” says Reid. “I’m sure New Line thought it was—but it transcended that.” Still, there were specific moments that exhibited what it’s like being black, for better and for worse. The Full Force trio threaten Kid at every turn, but the violent and almost comically racist police antagonize everyone throughout the movie. There are consequences for the characters in House Party—simply for existing—that the likes of Ferris Bueller didn’t have to consider. “This was a teen movie like all of the John Hughes movies and all that,” says Reid. “But look what we had to navigate. The white dude doesn’t have to deal with half of this, all he has to do is wake up and shit is lovely. We have obstacles. But Reggie did it in a way that wasn’t overbearing or heavy-handed.”

House Party’s commercial triumph yielded more opportunities for its cast and crew. After getting offers from every studio in town, Hudlin’s big hit came following a phone call from Eddie Murphy. 1992’s Boomerang, which grossed $131 million globally against a $42 million budget, proved House Party was no fluke. A number of familiar faces from House Party were part of the ensemble cast: Lawrence, Witherspoon, Bebe Drake, Campbell, and Mitchell. House Party’s success funneled most of its cast into steady work (Mitchell has worked consistently as an actor since) or starring roles (Lawrence and Campbell landed the Fox sitcom Martin, in 1992). It spawned four sequels—two of which starred Kid ’n Play, who also secured a short-lived NBC cartoon in 1990 and a Marvel comic book series in 1992, the same year they starred in Class Act.

House Party’s resonance has now spanned generations. People re-create the dance-off at weddings, while a torrent of GIFs have preserved the scene on hallowed social media ground. While white executives at the time may have brushed House Party off because it seemed too impractical to succeed, there’s now entire generations who grew up on the movie. “To hear Method Man’s story of how he took this girl that he was really feeling on a date to go see House Party,” Martin says, “it just blew my mind that someone like Method Man was telling me this hilarious story about a coming-of-age moment in his life where House Party played such an important role.” Reid remembers being accosted by a child who recognized him from the film. “I was in Atlanta a few years ago and this little girl, like 6 years old, ran up on me,” he says. “She said, ‘You got a whoopin’ from your pops.’ I was like, ‘How’d you know I got a whoopin’ from my pops?’ She said, ‘My auntie watches that movie all the time.’ They’re passing it down.” George still enjoys reciting his signature lines. “Thirty years later, I’m still saying, ‘I’m gonna kick your fuckin’ assss,’ because people are still asking me to say it all the time,” he says with proud laughter.

“Thirty years later, I’m still saying, ‘I’m gonna kick your fuckin’ assss,’ because people are still asking me to say it all the time.”

“Lou Bowlegged Lou” George

There’s a good chance House Party’s influence may never fade. In February 2018, LeBron James and his SpringHill Entertainment partner Maverick Carter announced that they’d be co-producing a modern take on the film with a script written by Stephen Glover and Jamal Olori, most notably of FX’s Atlanta. Both Reid and Martin are eager to see how the concept translates in the modern era and for the new handlers to succeed at that. “Let’s get a new crew of young’uns up in there to tell it their way,” says Reid.

“I’m honored they think that much of it to try and make it happen,” Martin adds.

What can’t get lost in all of this is how House Party helped broaden the depictions of black people in cinema at a crucial time. “This is the best time in history to be a black filmmaker,” Hudlin told The New York Times in 1990. Numerous black films were released the following year: John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood, Mario Van Peebles’s New Jack City, Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, Lee’s Jungle Fever, Townsend’s The Five Heartbeats, Bill Duke’s A Rage in Harlem, Matty Rich’s Straight Out of Brooklyn, and George Jackson and Doug McHenry’s House Party 2, just to name a few. Although Hollywood’s interest in black stories and filmmakers dissipated heading into the 2000s, the 2010s marked another upswing. Directors like Barry Jenkins, Ava DuVernay, Ryan Coogler, and now Jordan Peele are currently thriving while telling very different black stories. “The truth is that it’s a cycle, but every cycle gets bigger and better,” Hudlin says. “The movies are bigger—bigger budgets, global reach, better filmmaking.”

“Black people are not a monolith” is a refrain that will likely (and unfortunately) be repeated until the end of time, but House Party’s immediate success and lasting impact are hard evidence that it’s true. “It widened the industry’s perception and understanding of who black audiences are and what they want,” Grillo says of its legacy. “And created a bridge to widen the understanding and perception of black culture to the rest of us.”

Julian Kimble has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Undefeated, GQ, Billboard, Pitchfork, The Fader, SB Nation, and many more.