‘Boomerang’ at 30: Think of it as the Robin Givens Rom-Com

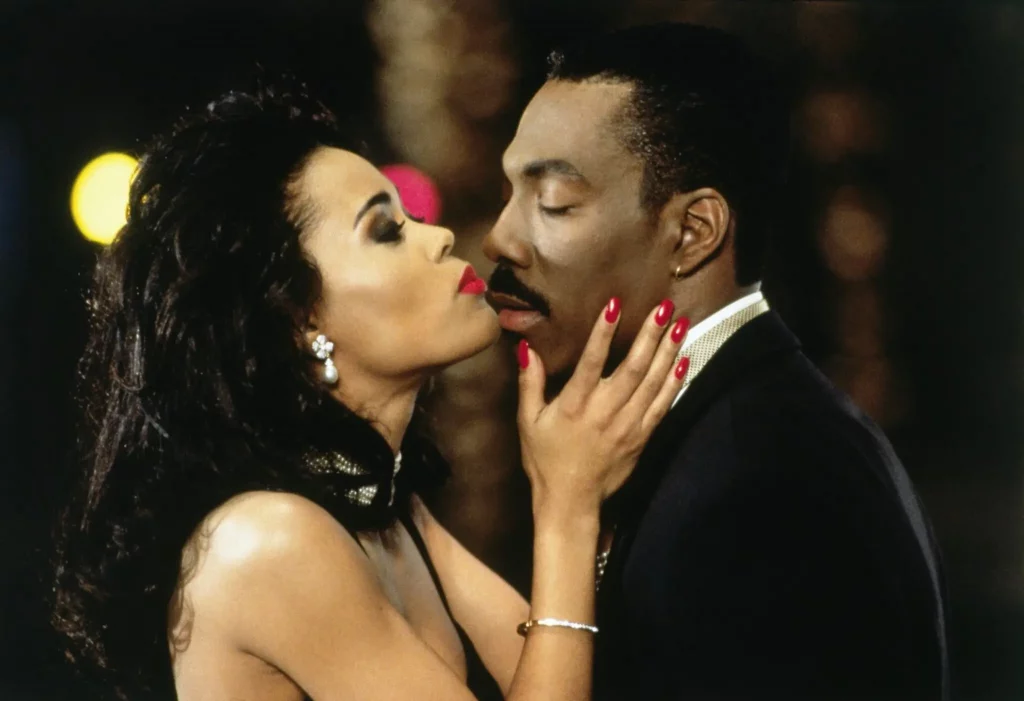

It’s remembered as Eddie Murphy’s bid at romantic stardom and as a key point in Halle Berry’s career. But the riveting antagonist arguably created a new archetype.

Salamishah Tillet | The New York Times

It was the summer before my first year of college, and I was enthralled by a movie (and its music) that had just arrived in theaters: “Boomerang,” starring Eddie Murphy. But I was drawn to the movie’s antagonist, Jacqueline Broyer, the glamorous, ambitious advertising executive. Played by Robin Givens, she was one of the few African American female characters to be the main love interest in a romantic comedy at the time.

My attention, however, was supposed to be on Murphy. That’s because in 1992, “Boomerang” was intended to be the film that turned him into a romantic leading man. Having risen to stardom in the 1980s with a series of hit comedies — “Trading Places,” “48 Hrs.,” and “Beverly Hills Cop” — he entered the 1990s aiming for more culturally nuanced films. The idea was that he would play more complex characters, like the debonair advertising executive Marcus Graham in “Boomerang” (1992), his first and only rom-com.

“We’re calling this our Cary Grant picture,” Brandon Tartikoff, then chairman of Paramount Pictures, told The Los Angeles Times, explaining that while audiences would get the “funny, smart, hip” Murphy they loved, the film would “mark a greater sensitivity” in his roles.

Directed by Reginald Hudlin of “House Party” fame, “Boomerang” was, in many ways, a success. It was among the highest-grossing movies of the year, eventually earning $70 million domestically and $131 million worldwide. Its soulful soundtrack, which I played on repeat during the summer of 1992, was also a hit. Produced by Kenneth Edmonds, known as Babyface, Daryl Simmons and Antonio Reid, known as L.A., it included Boyz II Men, A Tribe Called Quest and newcomer Toni Braxton, and reached No. 4 on the Billboard 200.

But most critics panned the film. In The New York Times, Janet Maslin described it as an “uneven, ostentatiously upscale comedy,” while The Los Angeles Times’s Kenneth Turan considered it “a multimillion-dollar vanity project.”

They were talking about one of the few films at the time to feature a majority Black cast and — in an era when social realist movies like “New Jack City,” “Boyz N the Hood” and “Juice” dominated — to show African Americans existing in a world unburdened by guns, drugs or tragic death.

Instead, “Boomerang” was a mix of fantasy and nostalgia. In a nod to an older generation of Black Hollywood glamour, the film cast the legendary Eartha Kitt, who as the sultry and purring Lady Eloise played off her iconic role as the first Black Catwoman. At the same time, Grace Jones, in the role of the prima donna Helen Strangé, appeared as an over-the-top version of the public persona that made her such an exotic muse for Andy Warhol, Keith Haring and her frequent collaborator and partner from 1977 to 1984, Jean-Paul Goude.

Aside from the stellar ensemble of David Alan Grier, Martin Lawrence and Chris Rock, the movie is best remembered today for Halle Berry. She played Marcus’s colleague turned girlfriend, Angela Lewis, the down-to-earth artist whom he cheats on with Jacqueline but who wins his heart in the end. Between the romantic comedy “Strictly Business” the year before and “Boomerang,” Berry was soon able to expand the types of roles for which she’d be considered after her seminal performance as a drug addict in Spike Lee’s “Jungle Fever” (1991).

As for “Boomerang,” seen 30 years later the women’s big hair and shoulder-pad suits make it seem dated, while Marcus’s sexism and the film’s slapstick homophobia are jarring. But I was also reminded why my 17-year-old self was so drawn to the film in the first place. “When Harry Met Sally” might have modernized the rom-com gender dynamics for my generation, but Jacqueline was an outlier. Her work ethic, confidence, intellect and medium-brown complexion were rare in a Hollywood that hardly ever cast African American women as romantic leads.

And that was all Robin Givens. I first became enamored with her when she played Darlene Merriman, the well-dressed, sharp-tongued, hypercompetitive student in the mainly white honors class on the ABC sitcom “Head of the Class.” As an awkward Black girl at a predominantly white high school myself, I overly identified with characters in similar situations like Darlene or Lisa Turtle (Lark Voorhies) from the sitcom “Saved by the Bell.” But unlike Lisa, who never seemed to have a love interest, Darlene always seemed in command, making me want even more to emulate her fashion sense and the ease with which she flashed her wit and smile.

Despite Givens’s popularity on that show, when “Boomerang” premiered in 1992, it was her comeback vehicle. The star, a prodigy who had matriculated to Sarah Lawrence College at 15 and planned to go to medical school before pursuing acting full time, had married the heavyweight boxer Mike Tyson in 1988, only six months after meeting him, at the height of her career. When she ended their yearlong marriage, she was publicly caricatured as a golddigger seeking fame and wealth.

I remember the moment that stereotype really took hold. I was 13, and watching the “20/20” interview that Givens and Tyson did with Barbara Walters in September 1988. Sitting next to a conspicuously subdued Tyson, Givens disclosed that he was a “manic depressive” who had repeatedly physically abused her. Her admission that her time with him had been “torture, pure hell, worse than anything I could possibly imagine” garnered little public sympathy in that pre-#MeToo era.

After their divorce a few months later, Givens’s career was never the same. “Robin was a very controversial piece of casting,” Hudlin said in the audio commentary that commemorated the film’s 10th anniversary. “A lot of people were nervous that there was a lot of dislike in public because of her past with Mike Tyson. But, I thought that actually made her perfect for the role, that she was this formidable person and a match for Eddie Murphy, who also had an intrepid reputation as a ladies’ man.” He added, “I wanted the audience to feel like this would be a fair fight.”

Givens and Murphy had dated briefly before when she was a sophomore in college, and he was a cast member on “Saturday Night Live.” One of their most memorable tête-à-têtes onscreen occurs when Jacqueline, wearing a gray trench coat, has missed Marcus’s carefully curated romantic date. She swoops into his apartment to apologize for not calling or canceling. When he asks her to leave, she starts to do so, only to pause and share her big reveal: She is wearing lingerie underneath her coat. Once Marcus succumbs to her seduction, his comeuppance is now all but guaranteed as he falls even more deeply for a woman who does not want a monogamous relationship.

As Givens detailed in her 2007 memoir, “Grace Will Lead Me Home,” she retreated from the spotlight after “Boomerang.” She spent the next decade healing from her marriage to Tyson and raising her two young sons. More recently, Givens could be found shaping another teenage audience as the fabulous mayor and mother of Josie on CW’s “Riverdale,” and now she plays the powerful Jada Jet, chief executive of Jeturian Industries and mother of the heroine in “Batwoman.”

Her characters are as fashionable as ever, but their glamour now also comes with Givens’s well-earned grit. In the short-lived BET series “Boomerang,” Jacqueline’s son, Bryson (Tequan Richmond), was ambitious to a fault. “We imagine that Jacqueline’s place is probably cold, quiet and empty,” the show’s co-creator Lena Waithe said to me in a 2019 interview.

But I think that she actually birthed a new archetype: a Black woman who loves her job, is sexually autonomous and has a style all of her own. And when we look at her today, viewed alongside Black female leads on older shows like “Being Mary Jane” and “Scandal” or the more recent “Insecure” or “Queen Sugar,” Jacqueline seems more like a forerunner and a character worthy of being the star of a movie all by herself.