When "Django Unchained" opens in theaters Dec. 25, audiences will finally see just what Quentin Tarantino has wrought with his provocative, ultraviolent slave-era Western. But that big-screen version is a long way from the screenplay Tarantino originally wrote that sparked a burst of excitement (along with juicy debate) when it first surfaced online in 2011.

Since then, scenes have been axed, dialogue has been added and major sections have been completely rewritten. Even the climax of the film was ditched — no longer does the titular character, played by Oscar winner Jamie Foxx, ride through town on his way to the Candyland plantation to blow up the master’s house. (Not to worry: Foxx himself claimed recently, "The new ending trumps it because Quentin made it a ‘ghost story.’")

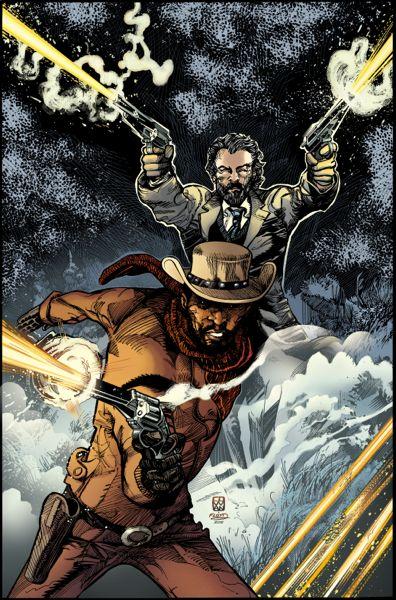

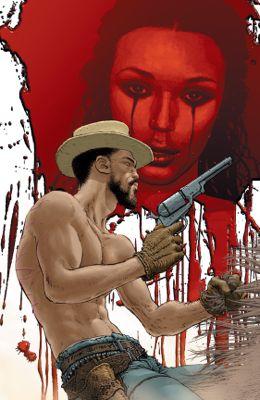

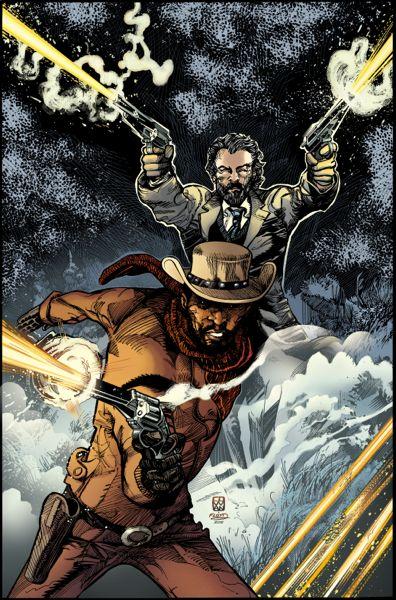

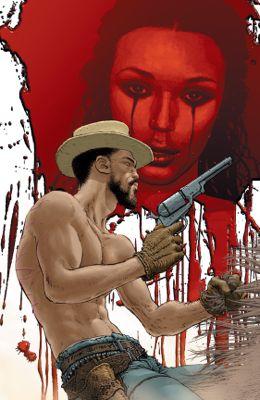

But fans of that original version will still have a chance to check out what it might have looked like visually, since Tarantino’s script has been adapted into a comic book series by Vertigo/DC Entertainment. The first of six installments drops Dec. 19; the second, which features a cover by Denys Cowan revealed here for the first time, hits Jan. 30 (three and four go on sale in February and March). Think of the comic series as an alternate version — that happens to come out first.

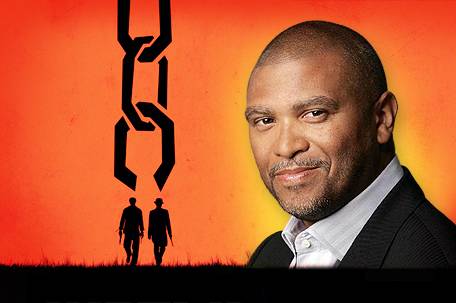

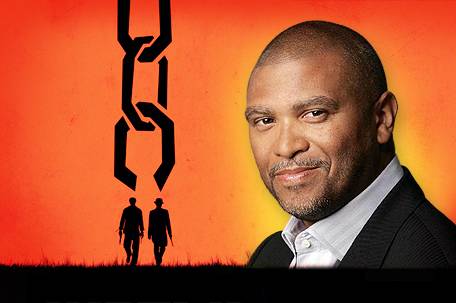

"There’ll be a lot of scenes in the comic that are not in the finished film," says "Django" producer Reginald Hudlin, whose comic book credits include Marvel’s "Black Panther" and "Birth of a Nation." While putting the final touches on the film, Hudlin took some time to give Indiewire his first in-depth interview about it — plus his thoughts on black superheroes, nerding out with Tarantino and the challenge of translating a 168-page screenplay into panels and word balloons.

Who came up with the idea for a "Django Unchained" comic book?

It kind of happened organically, actually. We were getting proposals to publish an illustrated screenplay, meaning it would be the screenplay with a bunch of photographs from production, and Quentin didn’t really want to do that. He believes the screenplay is an artistic medium in itself. He loves publishing his screenplays, but he wants them to stand alone and not have pictures as a crutch; either the writing works or it doesn’t. And when Quentin gave me that response to the offer I said, "Well, I get that. And, in fact, I was kind of disappointed because when I read ‘illustrated screenplay,’ I thought they were talking about a comic book adaptation." Then he lit up, like, "Yeah. Now, that’s what I’m talking about! That would be fun." [laughs] I agreed, so I reached out to my friends in the world of comic-book publishing and we got it going.

Has a slave ever been the hero of a comic book?

There haven’t been many, but yes. I mean, I have a great appreciation for the medium and so does Quentin. His specialty is, in whatever you’re talking about — film, television, comic books — he will mention very obscure characters and titles. For example, we talked about comic books — specifically the subcategory of Western comic books — and how big a fan he was of "Gunhawks," which had a black slave who was teamed up with a Confederate soldier. To me, that’s typical Marvel. [laughs] Like, what’s the boldest, craziest combination we can put together? The fact is, as per usual, comic books are bold and will go to provocative places. I can also say, pretty confidently, that no one’s ever seen anything like "Django" before.

The plot for "Django" revolves around a newly freed slave in the antebellum South attempting to rescue his lost love, Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), who was sold to another plantation. Though slaves could not legally marry during that period, did Django and Broomhilda consider themselves husband and wife?

You’re asking the question we bring up in the movie. Schultz [Christoph Waltz’s character] tells Django, “I didn’t know slaves recognized the institution of marriage.” And Django says, “Me and my wife do.” I mean, at the end of the day, doesn’t it come down to that? Marriage is a state of mind. Plenty of marriages on paper mean absolutely nothing.

Speaking of things on paper that aren’t necessarily binding, the original “Django”script went through numerous changes during production, and I heard that the gang rape of Broomhilda was toned down considerably. Quentin decided to shoot it in a way that protected Kerry while still conveying that something horrible happened to her character. Were those changes a direct result of her conversations with you and Quentin?

Let me answer that by making a broader statement. Quentin writes these scripts, and obviously he’s one of the best writers we have in our business right now. As the crew, we tend to treat his scripts with great reverence, like, “let’s figure out how to execute this exactly as he wrote it.” Quentin, though, looks at the script very much as a living document. He’ll show up on set with some new dialogue written on lined paper that he’s ripped out of a notebook and give it to an actor and say, “Learn this.” [laughs] And we’re going, “WHAT?” Then we see what he’s doing and say, “Oh, my God.”

Because it’s so much better.

We were completely happy before. But Quentin is constantly trying to figure out how to elevate, and part of that is talking with his actors. He’s not necessarily trying to appease his actors. But they are his partners, and he listens to them for their emotional truth.

Can you give us an example?

There was a whole other scene that kind of kicks off the third act of the film. Quentin knew the scene worked for every character except one, Jamie’s character, and when we were rehearsing it, Jamie said, “Oh, I’d play it this other way.” Quentin said, “Oh, really? I didn’t think you’d do that.” Jamie said, “Definitely, I’d play it like this…” That previous concern Quentin had, combined with Jamie’s instincts, made Quentin rewrite the third act of the movie! He always wants things to be true. That’s why he shoots the movie in what he calls “emotional order,” meaning it’s not quite in continuity order. But his thinking is, here’s a big scene, and based on how that goes maybe I don’t need so much of this other stuff, or maybe I need more of something else. Those things happened throughout the process of making the film.

You and Quentin seem like a very unlikely team. How did you first meet?

We met years and years ago. I’m friends with Pam Grier, who invited my brother Warrington and I to an awards event where she was being honored for her work in “Jackie Brown.” Quentin was presenting the award. And as soon as we met, Quentin said, “I saw that special you did for HBO, ‘Cosmic Slop.’” Now, this is something very few people have seen. It’s an obscure part of my filmography. And Quentin goes, “I don’t know why you did that short ‘Space Traders’ [about aliens who offer to buy the African American population] for HBO. That’s a feature. You blew that!” I was like, whoa. Then I thought about it and said, yeah, you know, he’s kind of right. [laughs] That kind of started our relationship, where we would meet up whenever and talk very, very passionately about movies, about everything.

Do you ever get competitive with each other when it comes to pop minutiae?

“Competitive" is not the right term. It’s more like we “revel in our nerditude.” I remember overhearing my assistant describe our interaction to someone. He said, “Yeah, Reggie and Quentin will talk, and then they’ll just go to a place and no one knows what they’re talking about.”

Is there any talk of releasing Quentin’s earlier films, such as “Pulp Fiction,” as comic books?

Funny you should say that. When we were looking at the “Django” pages, we were lamenting that we hadn’t started this a lot sooner. And I said, “Well, maybe it’s not too late.” So, yes, that conversation has started. I think comic books are part of the complex strain of DNA that make up what people think is the Tarantino style of storytelling. You’ve got all kinds of things that go into that mix. And for someone like myself, who never understood why he never did anything in that medium, I was very excited to shepherd “Django”into the comic book format.

Tarantino’s scripts are extremely quotable and dialogue-heavy. How do you go about adapting one?

I was a little intimidated at first. But if you just break up the story into the appropriate number of panels, it actually flows really well. When I was showing Quentin the first 10 pages of the book, I said, “Look, we’ve got it all in there, and the page isn’t drowning in word balloons. You still have plenty of room for the art.

Can you talk about the decision to go with R.M. Guera for the book’s illustration, and what kind of direction Quentin gave him?

We looked at a lot of artists, and Quentin picked R.M. Guera, who has done great work but is best known for “Scalped,” which is a kind of noir series among Native Americans set on a reservation. He’s a brilliant artist, and that sensibility is perfect for what Quentin’s doing. Also, R.M. already worked with Quentin, adapting a couple of scenes from “Inglourious Basterds” for Playboy magazine. “Django” was that same approach: Don’t draw what’s in the movie�; draw what’s in the script, which in some ways is different from what’s in the movie. We also have a great lineup of different cover artists: Jim Lee, Denys Cowan, Alex Ross and Frank Quitely. They all do their interpretation of Django. I get excited about projects like this, because I also feel like it’s a way to help support a medium that means so much to me.

It’s been a while since the comics industry has seen a new iconic black superhero. Do you think “Django”has the stuff?

He could. I’m committed to the concept of black superheroes, no matter what. And I certainly consider Django a superhero.

The first commercial black superhero was “Black Panther,” which you helped revive in 2005.

That’s right. When I was writing “Black Panther” for Marvel, I told them I want to give back to that next generation, and the series turned out to be a huge success. “Black Panther” is the biggest seller in the Marvel Knights line of animated DVDs. It out-sold Joss Whedon’s “X-Men,” which is pretty amazing given the brand power of those two great names. It out-sold “Iron-Man Extremis.” BET, who reluctantly aired the series at midnight, keeps re-running it because it gets a huge ratings bump every time, without any marketing and promotion. The show has become this amazing cult hit. [Hudlin was BET’s president of entertainment from 2005 to 2008.] A lot of my interest in comic books is diversifying the audience base. One of the nicest compliments I ever got was from a comic book retailer who said, “Reggie, we love when your comic books come out because we get different people coming into the store.” By “different,” he didn’t just mean black, he meant not the same people who come in every Wednesday. When I go to a comic book signing, there are tons of women. I see adults and kids — Latin, Asian, white, black — and I think that’s healthy for the industry.

Are you still planning a big-screen version of “Black Panther?”

Yeah, but those decisions are up to Marvel. Certainly, Stan Lee [who created the character with artist Jack Kirby in 1966] has said on multiple occasions he wants a “Black Panther” movie to get made. People are constantly asking me, “What’s the holdup?”

And what’s going to happen to Django when the miniseries wraps up?

Don’t know. Of course, I want very much to see the further adventures of Django. Quentin and I have talked about what those might be. But I want to see it in a feature film, and I don’t want a comic book to pre-empt or put him off doing a sequel, even though Quentin’s [officially] never done a sequel in his life and may never do one. All I know is we’ve got a great movie coming out, and we’ve got a great comic book, and we’ll see what happens after that.

Craigh Barboza is a New York-based freelance writer. His work has appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Uptown, USA Weekend and Vibe.

Talk about it on HEF – the Hudlin Entertainment Forum

Comment

+ Permalink

Dancing With Jamie Foxx and Quentin Tarantino

By Melena Ryzik

Even before the strong showing for “Django Unchained” at the Golden Globe nominations on Thursday, Harvey Weinstein was in a good mood. At the film’s premiere, hosted by the Cinema Society on Wednesday night, he stood at the front of the Ziegfeld Theater and crowed about the honors that this Weinstein Company release had already garnered: a host of nominations from the NAACP Image Awards.

His enthusiasm was doubled by Quentin Tarantino, the film’s director, who started singing in front of photographers and introduced his cast as though he were Don King on speed. “First name Jamie, last name Foxx,” he said, calling out the star. “Middle name — – ”

Well, let’s say it was a Tarantino-ism and, not a gentle one.

“Django Unchained,” a western-turned-slave revenge epic – which somehow also incorporates a German bounty hunter, an anachronistic Ku Klux Klan comedy bit courtesy of Jonah Hill, and countless references to Italian cinema – received glowing reviews from the opening-night crowd, even as they were sometimes fazed by the body count.

The afterparty, at the Biergarten at the Standard Hotel, was jammed with a who’s who of Mr. Tarantino’s friends and former stars, like Uma Thurman, Cameron Diaz, Sam Rockwell, Liv Tyler and Jeremy Piven. Diddy turned up, hugging Mr. Weinstein, slimmed down in a black T-shirt, and partying with Mr. Foxx and Samuel L. Jackson, another cast member. Sitting with his family was Christoph Waltz, his head shaved from a recent role in a Terry Gilliam film. An Oscar winner for Mr. Tarantino’s last film, “Inglourious Basterds,” he plays the scene-stealing German in this one.

At 1 a.m., when the party was due to wind down, Mr. Foxx got in the DJ booth and began a stream of thank-yous and shout-outs. (Why wait for an awards show stage?) The shout-outs included most of the horoscope (“My birthday is in two days,” he noted) and then called for someone to fetch Mr. Tarantino to join him. “Tell him to cut the story short – I know he’s telling a story right now,” Mr. Foxx said.

“A whole year of shooting the movie, 30 minutes to cut it,” Mr. Foxx said, when director turned up, trailing Ms. Thurman. “With everybody calling saying, What’s up? What’s up? What’s up?”

Of course, Mr. Foxx praised the final product, trimmed to two hours and 44 minutes. “With the subject matter and everything, the way it plays, I thought it was fantastic,” he said. “So kudos to everybody that had anything to do with this movie.” As his friend DJ Irie blasted hip-hop, the entire geometry of the room shifted toward the DJ booth, when Mr. Foxx, Mr. Tarantino and Ms. Thurman began dancing behind it.

Talk about it on HEF – the Hudlin Entertainment Forum

Comment

+ Permalink

How he’s shattering a genre with ‘Django Unchained’.

by Allison Samuels

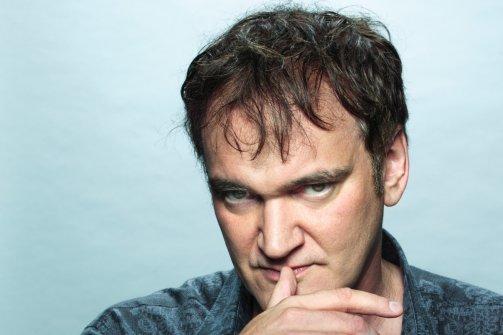

Good friends can talk about anything, and for director Quentin Tarantino and producer/director Reginald Hudlin, anything usually included long, good-natured chats about the mechanics of the African-American slave trade.

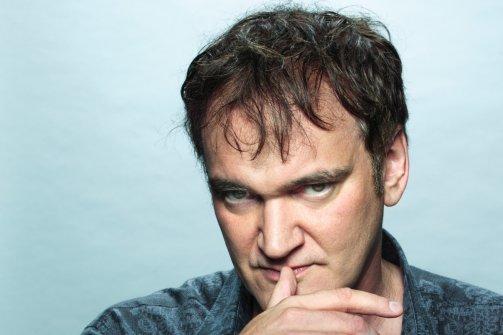

“The dynamics of the country are changing and people are talking about that,” says Tarantino… "I may take flak but I always do on some level with my work. Wouldn’t be a Tarantino film without some flak and criticism. I bet anyone who sees the film won’t be able to forget it—and that’s the point.” (Photograph by Jeff Minton for Newsweek)

The lack of a respectable film detailing the impact of slavery on this country fascinated both die-hard film buffs. Eventually both men—who met on the set of Jackie Brown in 1997—became obsessed with the idea of crafting a no-nonsense, somewhat entertaining film detailing the lesser known aspects of slavery. After one conversation with Hudlin stuck in his mind, Tarantino went to work on an all-or-nothing script. Six months later, �Django Unchained was born.

Set in the South just two years before the Civil War, Django Unchained (in theaters Dec. 25) somehow masterfully manages to present the haunting brutality of slavery while also infusing an outlandish humor only Tarantino could bring to the big screen. Moviegoers will be treated to the often controversial director’s deep love for the spaghetti western genre along with a blazing narrative of one man’s desire for vengeance and love. After being freed by a German bounty hunter, Django (Jamie Foxx) helps him track down a few bad guys for profit and then goes on a mission to find and free his enslaved wife (Kerry Washington).

“I was always amazed so many Western films could get away with not dealing with slavery at all,” says Tarantino, sitting in Todd-AO studios in Los Angeles where he was attempting to whittle the film to under three hours just after Thanksgiving. “Hollywood didn’t want to deal with it because it was too ugly and too messy. But how can you ignore such a huge part of American history when telling a story in that time period? It made no sense.”

It didn’t make much sense to Hudlin either. The director of the popular ’90s films House Party and Boomerang says he was baffled by the sugarcoated and abbreviated tales. “I hated all those films about slavery over the years. Any time Hollywood did deem it OK to talk about slavery, they were not worth watching,” says Hudlin, who is Django Unchained’s executive producer. “My idea of a great slave movie was Spartacus. Until African-American slavery was treated in that same manner, I had no interest in hearing what Hollywood had to say about the issue.”

With only two years of age separating Tarantino and Hudlin, they watched the same slavery-themed films as young kids—and then grew to hate them as adults. Titles such as Mandingo and �Uncle Tom’s Cabin roll off their tongues with joint eye rolls and audible sighs. The not�able period film Glory, starring Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman as freed slaves serving in the U.S. Army, gets an honorable mention nod from Hudlin.

“I liked the black characters in Glory,” says Hudlin, whose great-grandfather was a conductor on the Underground Railroad. “Didn’t see the point of the white ones. The true story was the slaves in the film. They should have been the main �focal point of the entire plot. But somehow no one figured that out.”

The faults of Glory aside, not much compares to the anger both men harbor toward the landmark television miniseries Roots. Written by Alex Haley and hailed in 1977 for telling the “complete” story of slavery, Roots remains the third most-watched miniseries of all time. It is also still considered the definitive mainstream portrait of slavery in the U.S.

“When you look at Roots, nothing about it rings true in the storytelling, and none of the performances ring true for me either,” says Tarantino. “I didn’t see it when it first came on, but when I did I couldn’t get over how oversimplified they made everything about that time. It didn’t move me because it claimed to be something it wasn’t.”

While many white directors might shy away from criticizing such an iconic symbol of African-American culture, �Tarantino doesn’t hold back. He’s confident in his knowledge of a time and subject most people know little about and would rather forget. He was also savvy enough to bring Hudlin on board. “There were times when I’d be filming a scene and really getting into it and Reg would just say, ‘Hey is this the story you wanted to tell?’ He’d bring the focus back if I got too carried away.”

One thing both men agreed on was a scene in Roots that served as an example of what not to do in Django Unchained. The last act of the final episode features the character Chicken George being given the opportunity to beat his slave master and owner in much the same way he’d been punished and tormented. In the end the character chooses not to so he can be “the bigger man.”

With only two years of age separating Tarantino and Hudlin (left), they watched the same slavery-themed films as young kids—and then grew to hate them as adults.

“Bulls–t,” exclaim both Tarantino and Hudlin in unison as they discuss the absurdity of the scene. “No way he becomes the bigger man at that moment,” says Tarantino.

“The powers that be during the ’70s didn’t want to send the message of revenge to African-Americans. They didn’t want to give black people any ideas. But anyone knows that would never happen in that situation. And in Django �Unchained we make that clear.”

Tarantino recalls a memorable scene where Jamie Foxx’s character is also given the opportunity to beat his former owner after he becomes a free man. “It was an emotional day on set and everyone was talking about how brutal it was because he beats the white off of his captor,” says Tarantino unapologetically. “There was no way that wasn’t going to be a part of the movie.”

Foxx shines as a man driven to punish those who tortured him, while also yearning for his wife, who was sold to another plantation years before. “It’s really important that this story is also a love story about a black man and a black woman,” says Hudlin. “In the midst of all the horrible things going on during that time, this man was in love and wanted his wife back. You don’t see black men in love too much on the big screen in slavery days, or modern times either.”

In a film already full of twists (not to mention costars Samuel L. Jackson and Christoph Waltz), Leonardo DiCaprio throws the ultimate punch portraying the young, handsome, rich plantation owner Calvin Candie. He owns Candyland plantation, where Django’s wife is being held, and thrives on the suffering he causes. The role is a marked departure for DiCaprio, who has spoken about how difficult the subject matter was to read, act, and convey on the big screen.

“He really embodied that entitled young male character perfectly,” says Tarantino. “His grandfather owned and made the plantation successful and his father kept it going in the movie. But DiCaprio’s character is just this kid who’s done nothing for the life he’s living. He’s living it up all the way with his decadence and greed, with no concern for how he got it.”

But neither an A-list cast nor �Tarantino’s past box office hits will be enough to save Django Unchained if moviegoers decide not to support a film that focuses so intensely on one of America’s darkest hours. Slavery is a subject both black and white audiences tend to avoid in theaters. Yet Tarantino and Hudlin say the timing for Django Unchained couldn’t be better.

“The dynamics of the country are changing and people are talking about that,” says Tarantino. “This time in history is a part of that conversation, and I love that we’re out there talking about it in the middle of the other films about Lincoln and whoever. I may take flak but I always do on some level with my work. Wouldn’t be a Tarantino film without some flak and criticism. I bet anyone who sees the film won’t be able to forget it—and that’s the point.”

Talk about it on HEF – the Hudlin Entertainment Forum

Comment

+ Permalink

By DeBorah B. Pryor

Reginald Hudlin and Quentin Tarantino first spoke about making a movie together on the topic of slavery over a decade ago – 15 years to be exact.

Hudlin told him that until a movie with the impact of a “Spartacus” (the Stanley Kubric directed epic that starred Kirk Douglas as a rebellious Roman slave and won 4 Oscars) could be done, he wasn’t interested.

But when Tarantino came to him years later and handed him a large script (“Django Unchained”) saying, “You planted the seed, now here’s the tree,” he couldn’t resist.

“A week later we were on location in Louisiana,” Hudlin tells EURweb publisher, Lee Bailey. He and director Quentin Tarantino came together to scout locations for the film.

“It’s a Quentin Tarantino film through and through,” the producer tells Bailey, who knighted him as the “genesis” of the film. He continues, “…it’s his writing, it’s his ideas, his characters. I just found it very impressive, you know, that this guy would think, ‘you know, I’m gonna honor the fact that, that conversation put me on a road.’ That just said a lot to me about who he is as a person,” says Hudlin.

Although the film doesn’t open until Tuesday, Christmas Day, it has been a highly anticipated work in Hollywood for quite some time, and there has been a LOT of buzz from insiders who have already seen it. Bailey asks Hudlin to identify some of the challenges of doing a film about this highly sensitive topic.

“Because it’s a Quentin Tarantino film some of the biggest challenges, which was to get financing, were very easy…Because we had a fantastic script…[and] world-class actors who wanted to appear in the film. But now you have the challenge of recreating a world and doing it in a way that it had never been done before; and shooting it across multiple states and managing the time and the logistics of a bunch of people – each of whom are movie stars – and now they’re acting in the same film. [We also had to] make sure we’re historically accurate and…the actual logistics of making sure the horses are safe. It’s an endless list of challenges you have to produce.”

In expressing to Tarantino in those early talks everything he didn’t like [about slave movies], Hudlin laughs as he recalls the only example he could think of to describe what he did like: Fred Williamson in “The Legend of Nigger Charley,” (a 1972 blaxploitation western directed by Martin Goldman) a film Hudlin saw when he was roughly 8-years-old.

“I remember leaving the theater feeling great! And I said, there’s no reason why I shouldn’t leave the theater feeling great. I want a catharsis!! And that’s what Django delivers,” Hudlin confirms.Bailey laughs out loud upon hearing this; and feeling the need to explain the outburst adds that Django is ”hilarious,” and he can’t understand why because it is about such a horrendous time. Hudlin breaks it down to him in an almost prophetic fashion.

“A lot of people don’t understand the difference between serious and solemn,” Hudlin explains. “You can be serious without being solemn and that’s what Quentin does beautifully in all his work. And it was an incredible total balancing act that he pulls off because he knows how to tell a story well.”

The producer says that Tarantino’s focus is always on telling a great story; not so much on the time or history that the story is drenched in. He adds that telling a great story involves humor, which makes it a story you want to see, not one you feel obligated to see as some kind of cultural duty.

But even with good storytelling, bad timing is quite frankly, a bitch!

The reality of such an undeniably violent movie heading to theaters NOW, as the country remains shocked to its core over the horrific recent violence in Newtown; where families continue to bury the 20 children and 6 adults killed at the hands of a lone gunman only days ago can’t be shoved aside. In fact, due to the tragedy, Hollywood had the sensibility to cancel the premiers of two major movies – one being Django Unchained. Lest we forget the unfortunate timing that presented an opportunity to recall Jamie Foxx as host on SNL just one week prior where, in the context of his 3-minute-plus “How Black is That” opening monologue, tells the audience, “No worries, I get to kill all the white people in the movie. How black is that?” Though no doubt an “in bad taste” remark, irregardless of the fact that it is what he gets to do, these same words would probably have stopped at the nervous laughter it generated from a few audience members; had it not been spoken just one week prior to such a devastating and violent act.

Bailey asks Hudlin what effect he thinks the Newtown shooting incident will have on the film, and if he thinks Hollywood filmmaking will change as a result of it.

“I can’t speak for Hollywood,” Hudlin responds, “but I’ll just say in relation to our film, I think movies that deliver an exploration of who we are as a people and as a culture ultimately decrease violence, not increase it. And this film takes a really hard look at who we are as Americans; black and white, and the social and economic forces that shaped us. And I feel that if we understand who we are better, we will have better mental health as a people. Slavery is America’s original sin and we avoid it, blacks and whites alike. We’re all ashamed of our heritage of slavery, but if you avoid the past then you can’t heal, you can’t transcend. And that’s what we’ve got to do.”Hudlin, who is justifiably credited with being a pioneer of the modern black film movement, reveals an unmistakeable pride in working on Django Unchained, and a real admiration for Quentin Tarantino and the cast. He had the opportunity to go into theaters across the country and witness the response of audiences of diverse cultures watching Django. He thought it was great that everyone cheered at the same time, cried at the same time, was terrified at the same time, and laughed at the same time. And to those responses he concludes,

“It speaks to how far we have come together. That we can watch a movie as sensitive as this, and everyone literally be on the same page.”

To this we say, indeed, Mr. Hudlin. Indeed.

Talk about it on HEF – the Hudlin Entertainment Forum

Comment

+ Permalink