By DAVID BROOKE

After seeing the excellent Black Panther film I just want more. Sequels, toys, comics…give me anything and everything. Enter Marvel’s Black Panther Annual #1 written by three prolific Black Panther writers Reginald Hudlin, Donald McGregor, and Christopher Priest. This is gonna be good.

So what’s it about?

The official summary reads:

Your favorite teen heroes return to Los Angeles, but it’s not the same city they left so long ago. The Runaways try to stay off the radar, but the sins of their parents won’t make that possible…

Why does this matter?

Three stories, three writers, three artists and three very different stories. Seriously, this comic is fantastic because it shows different aspects of a great hero.

Fine, you have my attention. What’s good about it?

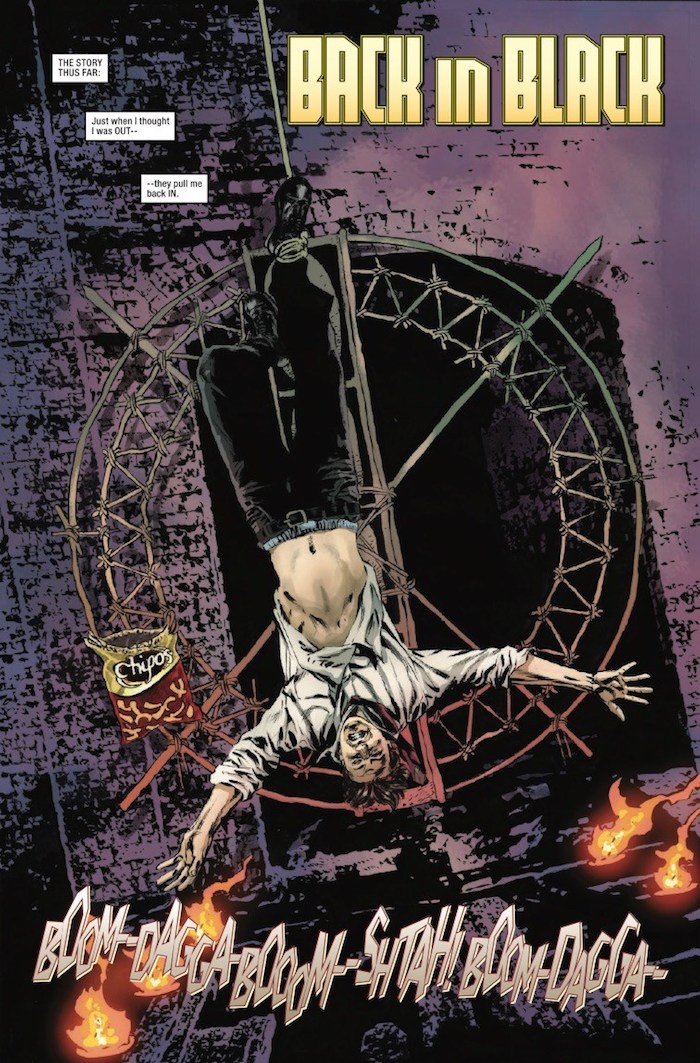

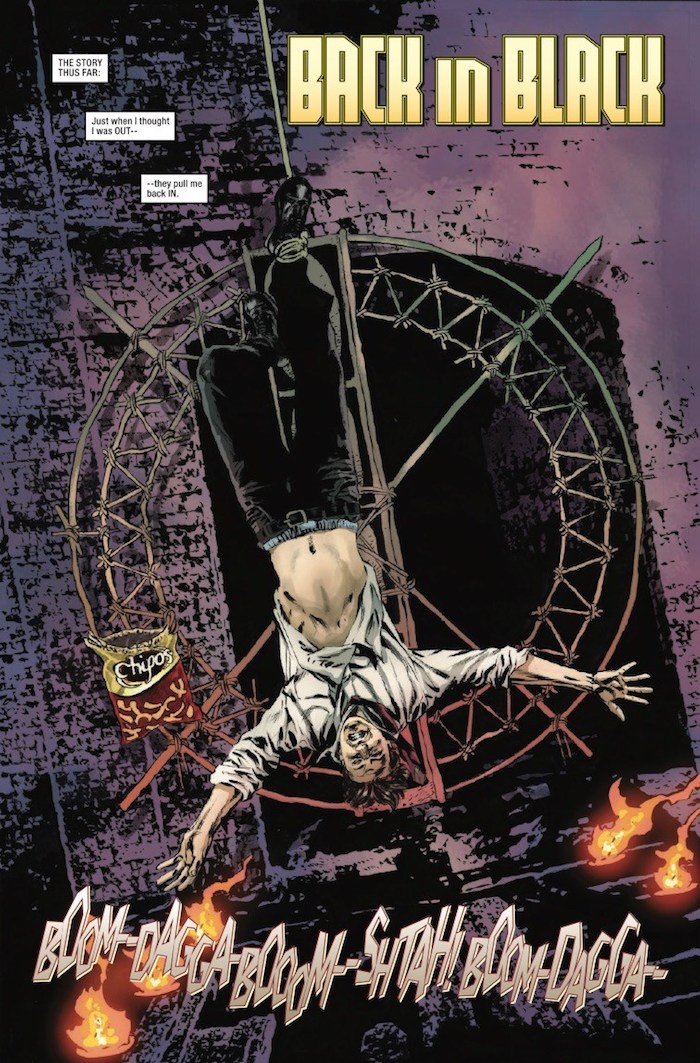

Christopher Priest opens this issue with art by Mike Perkins and colors by Andy Troy. Titled “Back in Black,” this story focuses on agent Ross, who has had one hell of a day. The story is questionable and ridiculous as he attempts to tell his superiors what happened. Shark attacks, Uber shootouts, and more. Priest plays up this character’s rather ordinary perspective even though this extraordinary adventure took place. As the story progresses Priest weaves in a call out to a major Black Panther supporting character and the bond Ross shares with our title hero. It’s a tale that you won’t see coming, but given how important Ross was to the film it’s a welcome tale.

Don McGregor writes the second story with art by Daniel Acuna titled “Panther’s Heart”. This story is nearly all narration and focuses on Black Panther attempting to save a loved one even though the odds are impossible. It’s a touching tale as it proves not even a superhero can win every battle. There are also some dazzling shots of Wakanda and some nice mythical style storytelling involving some mystical flowers.

The third story by Reggie Hudlin, with art by Ken Lashley and colors by Matt Milla entitled “Black to the Future Part II” is by far my favorite. This story is set in the future where Black Panther is a grandfather and Wakanda has risen as a world leader. As Black Panther tells his granddaughter of things he’s done and the wisdom he’s learned Hudlin drops some doozy anecdotes about superpowers being vanquished (Dr. Doom…dead?!) and alliances made between Atlanteans. It’s fascinating how Hudlin weaves in cultural elements like how helping others ends up looking like an attack, or the strategies a king must implement for the betterment of his people. Lashley excels with the art depicting nearly destroyed helmets and trophies helping to convey Black Panther’s historic run as a superhero now in his old age.

It can’t be perfect can it?

One could argue Priest’s story is severely lacking in Black Panther action, the second story with nearly no action at all, and the third mostly focusing on telling a story rather than visualizing it. These are all true statements, but each story is so unique and well told you’ll ignore such quibbles.

Is It Good?

An excellent annual particularly because it satiates your Black Panther thirst. Give this a read especially if you’re dying for unique tales all about one character.

RATING: 10 FANTASTIC

BUY NOW

Comment

+ Permalink

By Eric Francisco

T’Challa may be the hero of Marvel’s Black Panther, but everyone is talking about Shuri. In a new interview, the man who created Shuri in the Black Panthercomics reveals why he gave the King of Wakanda a younger sister, who he says was always going to take over as Black Panther at some point.

On Tuesday, former BET entertainment president and comic book writer Reginald Hudlin told Vulture why he came up with Shuri during his time writing Black Panther for Marvel Comics. For starters, it made sense that royalty would not have just produce one offspring. “It just seemed for me that, again, when you’re royalty, you’re not just gonna have one kid. You gotta have an heir and a spare, right?” Hudlin told Vulture.

Hudlin’s reasons didn’t stop there. As a father to a son as well as a daughter, Hudlin knew the power of gender representation. He also knew Shuri was going to take over for T’Challa as the Black Panther from the start.

“I wanted everyone who read the book to be empowered. I wanted girls who read the book to feel as empowered as boys. So, I wanted her to be smart and tough and brave and everything you think of as a Black Panther, so that eventually she would be a Black Panther as well. Basically, I wanted a Halloween costume for my son and my daughter.”

In a relaunch of Hudlin’s run in 2009, T’Challa was beaten out of the mantle of Black Panther (it’s a long story) and replaced by his sister, Shuri. Shuri served as the Black Panther of Wakanda for several years, until once again her and her brother’s roles were reversed. At the beginning of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s run on the comics in 2016, T’Challa is seeking a way to revive Shuri, who is suspended in animation waiting to be healed.

In Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, Letita Wright plays Shuri, portraying a somewhat younger and more energetic version of Shuri than Hudlin imagined in the comics. But just like the comics, Shuri is an engineering genius boosted by Wakanda’s near-endless supply of Vibranium resources. In the film, Shuri alone perfected Wakanda’s public transportation while also upgrading T’Challa’s Black Panther suit with unbelievable features. She also loves internet memes, but you’ll see that soon enough.

Comment

+ Permalink

by Brian Cronin

Welcome to Comic Book Legends Revealed! This is the six hundred and sixty-seventh week where we examine comic book legends and whether they are true or false.

As always, there will be three different posts for each legend this week!

COMIC LEGEND:

The Watcher showed up at the wedding of Black Panther and Storm because of a then-upcoming Black Panther event that never came out.

STATUS:

True

A year and a half ago, I wrote a “Left Unresolved” column about the Watcher showing up at Black Panther’s wedding to Storm. Now we’ll find out how it WOULD have been resolved!

First off, let me more or less repeat what I wrote then to set things up…

In Black Panther #18 (by Reginald Hudlin, Scot Eaton and Klaus Janson), the Black Panther and Storm got married in a wedding surrounded by world leaders and their superhero friends (even those that were currently embroiled in Civil War with each other over the Superhuman Registration Act).

Their marriage was relatively short-lived, as T’Challa annulled their union six years later (our time) in Avengers vs. X-Men #9 (by Jason Aaron, Adam Kubert and John Dell, based on a story by a bunch of writers)…

Now, up until Avengers vs. X-Men, when one of Storm’s teammates destroyed much of Wakanda, T’Challa and Storm had a happy marriage with a lot of fun adventures. I was a fan. They were especially good on the Fantastic Four (Hudlin and Dwayne McDuffie both wrote good adventures with the married couple as part of the Fantastic Four). However, whether you were a fan of the Black Panther/Storm marriage or not, I think it is fair to say that their marriage did not have a significant impact on the Marvel Universe. It was just too short.

However, when they got married, the wedding had a unique guest…the Watcher!

Even the Black Panther was, like, “Huh? Why’s he here?”

Since the marriage was annulled, the Watcher’s presence likely will never REALLY be explained in the comics. However, Victoria Johnson recently discussed the Black Panther with Reginald Hudlin at Vulture.com and Victoria got an answer to this unresolved plot point!

In Marvel comics, the Watcher usually shows up to witness major turning points in history. Is that why he was at their wedding?

The Watcher was there because this is a momentous marriage. The results of this marriage would be world-changing. There’s a story I never wrote called “World War Wakanda.” Basically, the Panther has taken this isolationist stance, like, “We’re not imperialist, we’re not trying to conquer other countries.” But the people are so paranoid, once he’s married to Storm and he starts this movement of helping mutants worldwide, ultimately he has to fight everybody. He is forced to take a more aggressive military stance on a global level.

That’s interesting. I really wish you got to write that.

[Laughs.] Well, you know, there’s a Black Panther Annual coming up soon. They asked me, Don McGregor, and Christopher Priest to each write a short story. So I wrote the epilogue of the “World War Wakanda” story in that book

Wow, that really does sound like it would have been an interesting storyline! I look forward to seeing the epilogue!

Thanks to Victoria and Reginald for the awesome information!

Comment

+ Permalink

By MIKAEL WOOD

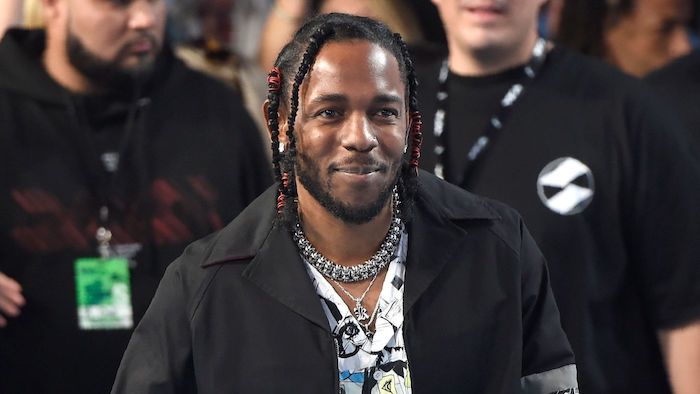

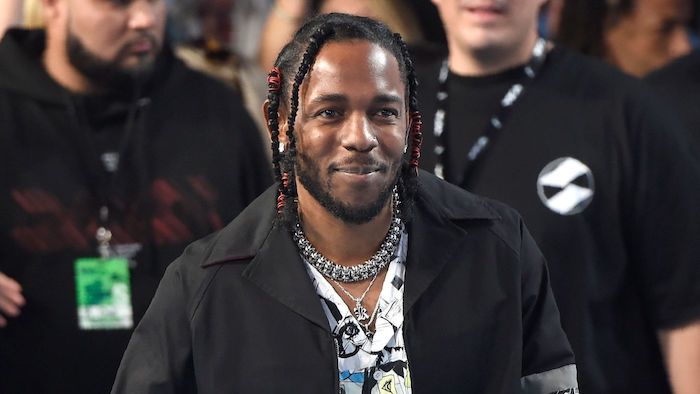

Kendrick Lamar curated the all-star soundtrack of “Black Panther” and appears on each of its 14 songs. (Chris Pizzello / Invision/AP)

There’s a scene in “Black Panther” — director Ryan Coogler’s breathlessly awaited Marvel Comics adaptation that promises to smash box-office records when it opens Thursday night — in which a bad guy busy raining fire from the passenger seat of a getaway car commands his driver to turn on some music.

“It’s not a funeral,” the bad guy sneers, and suddenly we’re being pummeled by “Opps,” a throbbing, darkly futuristic hip-hop tune by a trio of rappers led by Compton’s Kendrick Lamar, who put together the movie’s all-star soundtrack and appears on each of its 14 songs.

The villain’s line is a bleak joke of course, but he’s dead-on about his surroundings: “Black Panther” is most definitely not a funeral — and its wildly creative music accounts for much of its vital life force.

A superhero movie with a soul, Coogler’s thrilling and heartfelt picture radiates positive energy as it follows T’Challa, king of the fictional African nation of Wakanda, in his struggle to protect his prosperous homeland while simultaneously empowering marginalized people around the world with the use of the Wakandans’ advanced technology.

What’s more, the film — featuring a mostly black cast that includes Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong’o and Angela Bassett — is being viewed by many with hopes that it will begin a new era of African American representation in Hollywood cinema.

“This may be the night that my dreams might let me know / All the stars are closer,” SZA sings in “All the Stars,” a yearning duet with Lamar, and the lyric could be the inner monologue of a young woman watching “Black Panther” and finally recognizing an image of herself on-screen.

For all the ways in which it looks forward, though, “Black Panther” also proudly adheres to an established tradition of black movie music that stretches back decades — through “Boyz n the Hood” and “Waiting to Exhale” in the 1990s to “Purple Rain” and “Do the Right Thing” in the 1980s to “Super Fly” and “Shaft” in the 1970s.

The idea, in contrast with many of today’s more obligatory soundtracks, is not merely to assemble a collection of songs to wallpaper a blockbuster or to extend its pop-culture footprint to Top 40 radio (or to Spotify).

Rather, what connects these movies and their accompanying albums to each other is the shared determination to utilize music as a storytelling device — including tunes delivered from characters’ points of view — and to reflect the sprawl of an ambitious narrative with a soundtrack that coheres even as it showcases a diversity of styles.

There’s also a certain feel-good quality at work here — what the actor Craig Robinson referred to as “a hug for your soul” when he hosted the second of two “Black Movie Soundtrack” concerts at the Hollywood Bowl in 2016. (Those shows, by the way, were overseen by director Reginald Hudlin, who wrote for Marvel’s “Black Panther” comic in the early 2000s — and whose 1992 film “Boomerang” spawned a classic soundtrack of its own.)

Lamar plugs into that emotional current on “Black Panther: The Album” without flinching from the tough questions the movie asks about race and identity and the burden of leadership. With luck, the result will propel other musicians and filmmakers toward similar ambitions.

Often hailed as the most important rapper of his generation, the 30-year-old Lamar was an inspired choice to handle the project, for which he’s credited as executive producer alongside the head of his record label, Anthony Tiffith, known as Top Dawg.

Like Curtis Mayfield or Prince or Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds, to name three earlier soundtrack auteurs, Lamar understands how to package sophisticated concepts to make “entertainment that has artistic integrity,” as Coogler described it to me recently.

The director said he was drawn to the “introspective” quality of Lamar’s work, including last year’s Grammy-winning “Damn” album, with its thoughts on the personal costs of black achievement in Donald Trump’s America.

Yet Lamar spins a great yarn — so much so, Coogler pointed out, that he subtitled his 2012 breakthrough, “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” a “short film by Kendrick Lamar.”

“You always feel like you’re going on a cinematic journey with him,” the director said.

On “Black Panther” that journey is in part a physical one. With contributions from a deep bench of international talent, the album roves from Lamar’s native Southern California (also represented by Vince Staples, Anderson .Paak and various members of Lamar’s TDE crew) to Atlanta (2 Chainz, Future) and England (James Blake, Jorja Smith) and South Africa, where some of the soundtrack’s most gripping voices come from, including the singer Sjava and rapper Yugen Blakrok.

Guided by Lamar and his longtime studio partner Sounwave, along with a bevy of additional songwriters and producers, these artists together weave a dense and often gorgeous fabric of sound.

There are shimmering electro-R&B jams like Khalid and Swae Lee’s “The Ways” and “Redemption,” by the duo of Zacari and Babes Wodumo, a South African club star who imports the dance groove called gqom.

There are slow-motion ballads like Smith’s bluesy “I Am.” And there are rowdy hip-hop posse cuts like “King’s Dead,” which has Lamar trading verses with Jay Rock and Future and features a trippy interlude sung by James Blake.

“Opps” is another of those, with fierce rhymes from Lamar, Staples and Blakrok over a noisy beat that imagines a SoundCloud-era update of the Bomb Squad’s groundbreaking production for Public Enemy. (In “Black Panther’s” prologue, set in 1992, we see a Public Enemy poster hanging on a character’s wall — a nifty acknowledgment of the group whose “Fight the Power” still conjures visions of Spike Lee’s powder-keg Brooklyn.)

Like the movie, which ponders the value of open borders, the “Black Panther” album uses this variety to embody and examine ideas about the African diaspora at a time of increasing immigration control. In that it shares some DNA with Drake’s globe-tripping 2017 effort, “More Life,” which came out just weeks before “Damn.”

But where the famously self-absorbed Drake rarely deviates from his own point of view, Lamar on “Black Panther” frequently adopts the voices of T’Challa and the king’s rival, Erik Killmonger.

“I dropped a million tears / I know several responsibilities put me here,” he raps in the opening title track, before demanding, “What do you stand for? Are you an activist? What are your city plans for?”

That Lamar himself is acquainted with these questions only makes his portrayal more convincing, as was the case when Ice Cube did “How to Survive in South Central” in “Boyz n the Hood.”

“In L.A. heroes don’t fly through the sky of stars / They live behind bars,” Ice Cube rapped in that song, merging his perspective with that of his indelible character, Doughboy.

Nearly 30 years later, Lamar and “Black Panther” show how much has changed since then — and how much hasn’t.

Comment

+ Permalink