Most people haven’t seen Charles Burnett’s masterpiece KILLER OF SHEEP. You need to fix that. As I said in my comments, the work of art I compare it to the most is Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN. Here he is being given an Oscar for his work.

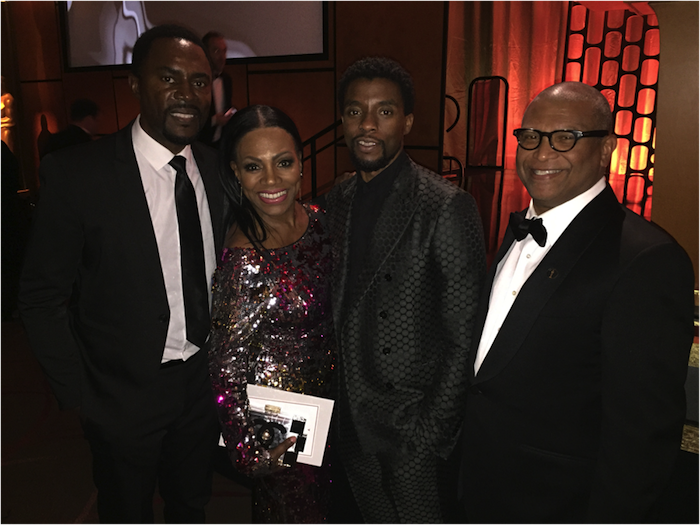

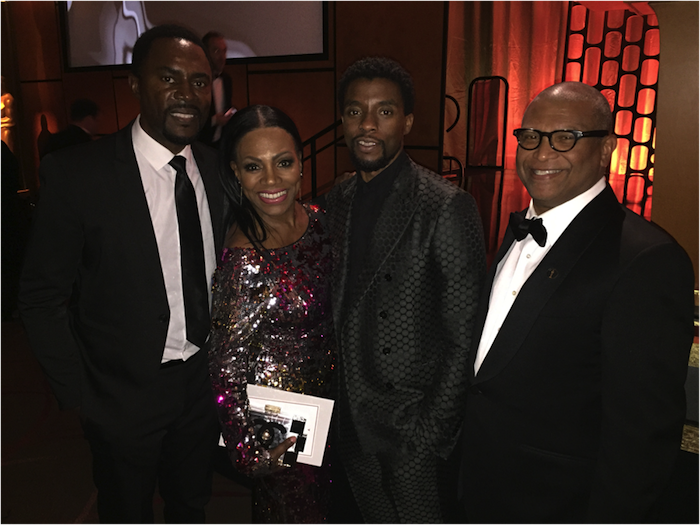

#blackexcellence in full effect at the AMPAS Governor’s Awards with Richard Brooks, Sheryl Lee Ralph, Chadwick Boseman and myself celebrating Charles Burnett.

Me and the terrific Tessa Thompson at the AMPAS Governor’s Awards. If you haven’t seen her in THOR: RAGNAROK yet, get on it!

Comment

+ Permalink

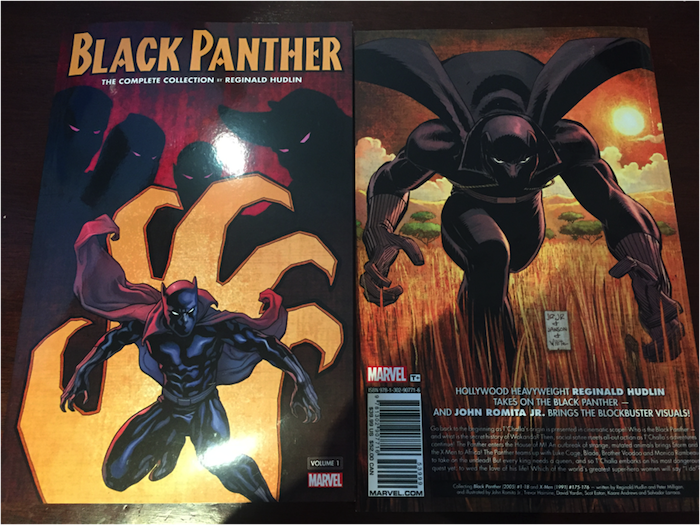

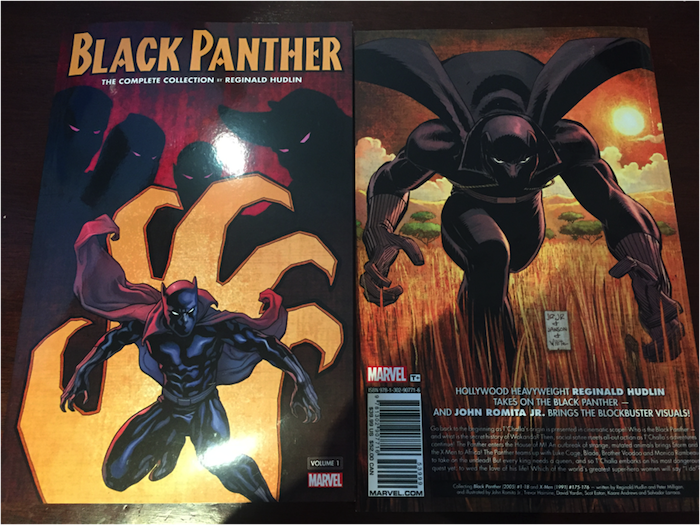

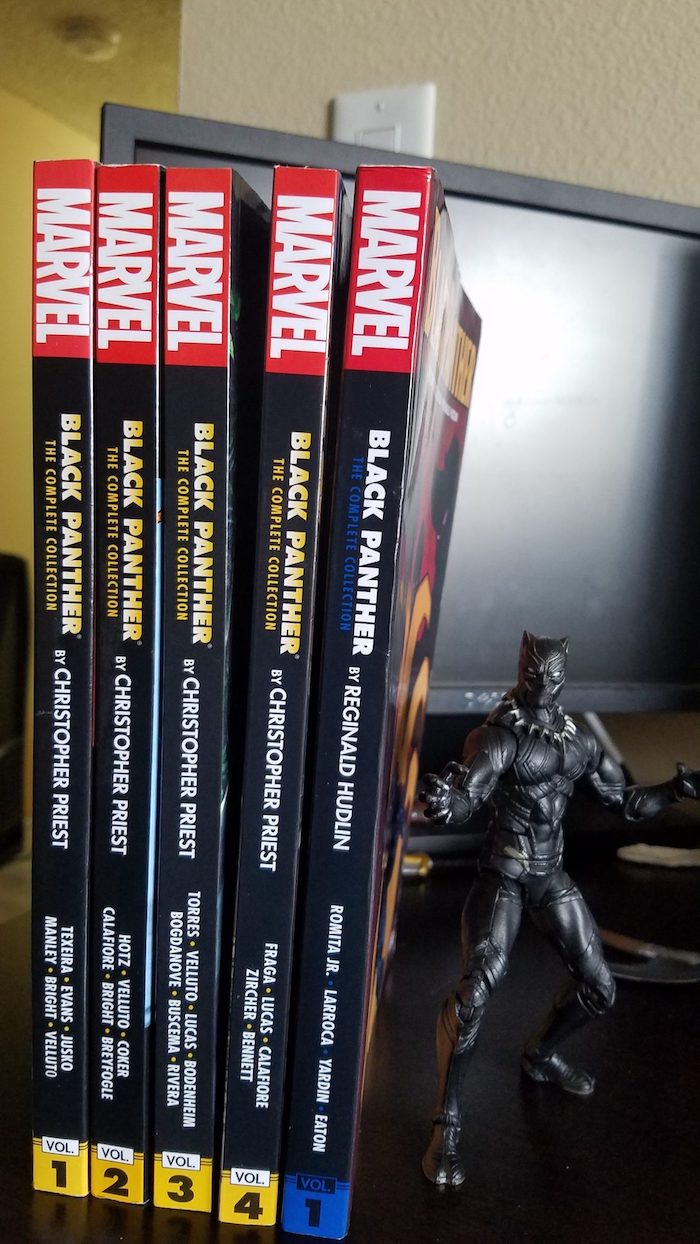

‘Black Panther by Reginald Hudlin: The Complete Collection Vol. 1’ review: Does its titular hero proud

By Robert Reed

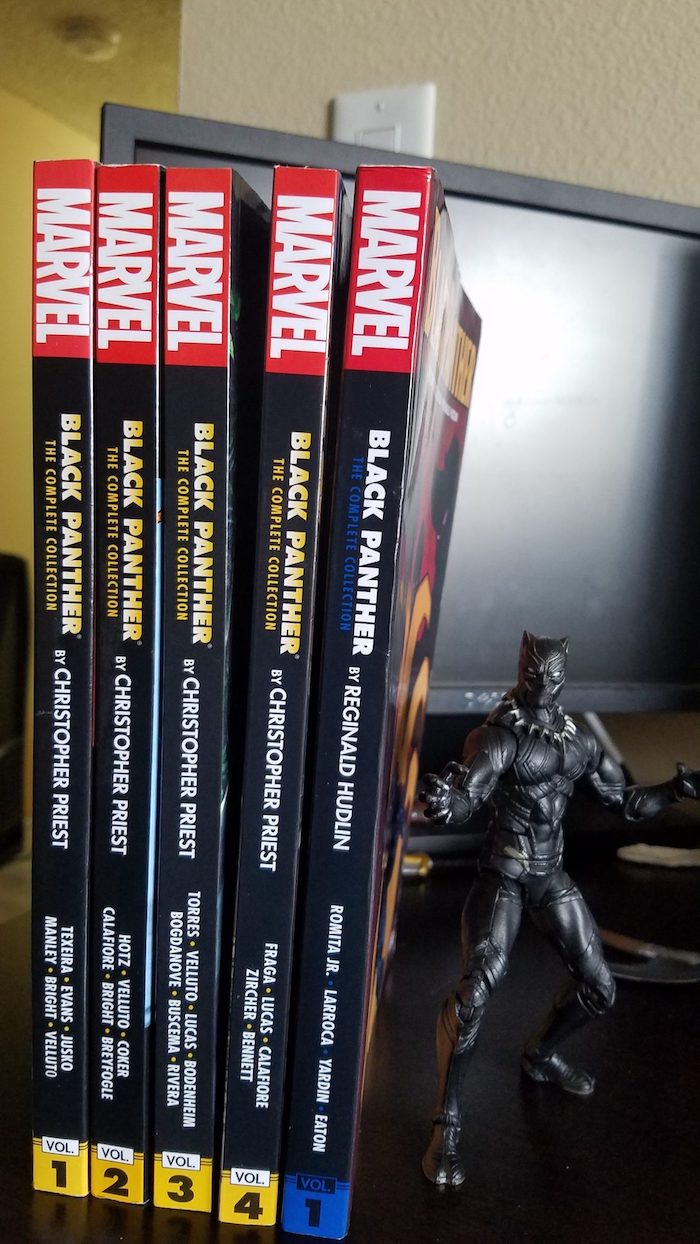

While Christopher Priest’s run on Black Panther is often touted as the definitive run on the character, Reginald Hudlin’s take is equally important due to the prominence he brought to Black Panther. Of course, prominence doesn’t always translate to quality, and this run hasn’t always been held in high regard. The question remains: is it good?

Black Panther by Reginald Hudlin: The Complete Collection Vol. 1 opens with the “Who is the Black Panther?” arc that serves as a fantastic introduction to the character and the mythos. The arc was initially part of the Marvel Knights banner and outside of the regular continuity before being retroactively folded in, and so while there are some basic changes (eg, Everett K. Ross no longer serves as an ally to T’Challa, T’Chaka’s death at the hands of Klaw is reworked from the original story by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee), this opening arc gets at the heart of Hudlin’s take on the character. The story is quickly paced, and draws on a number of characters from Marvel’s pantheon (something that remains true for the rest of the book) and shows just why the Black Panther is cool.

John Romita Jr.’s artwork is fantastic, providing stunning visuals of both ancient and modern Wakanda and some awesome fight sequences (including a two page spread covering Captain America’s WWII encounter with Wakanda). His T’Challa is handsome and intellectual, creating a visually interesting lead for the reader to follow.

Reginald Hudlin is great at balancing the emotionally powerful with the humorous, never falling into the pitfall of self-seriousness. The writing has a bit of self awareness to go along with its swagger.

Beyond this opening arc though, the collection takes a minute to find its groove. The crossover with X-Men (written by Peter Milligan with art by Salvador Larroca) and House of M are entertaining distractions, but they feel like interruptions before the book gets back on course with the “Two the Hard Way” arc.

Here, Hudlin begins to really shine, using Luke Cage’s experienced point of view to shine a greater light onto Black Panther. When one superhero admires and learns from another, it causes greater admiration for both heroes in the eye of the reader and Hudlin understands and utilizes that fact with great aplomb.

The climax of this collection, and indeed, its running throughline, is built around Black Panther finding a bride. And while marketing during the time may have led to a mystery around who that bride would be, Hudlin never hides the fact that Black Panther’s true love is Storm. This puts the X-Men crossover in context, while Black Panther and Storm had been connected to one another romantically as far back as Chris Claremont’s Marvel Team-Up #100, the relationship had only seen flashes of daylight since, such as in Priest’s Black Panther. To help the marriage seem “valid” in the eyes of fans, bringing Storm into the book earlier makes sense.

Hudlin also adds an unexpected layer of depth, highlighting that for T’Challa this isn’t only a romantic pursuit. It can’t be. He is a king and a king needs legitimate heirs to the throne. Hudlin does a fantastic job fleshing out both T’Challa and Storm (and what it means for a mutant to potentially be the Queen of a nation with as much political weight as Wakanda) and their relationship, and it gives the last third of the book a romance-adventure tone that isn’t often seen in superhero comics.

This lighter tone may not be to everyone’s liking, especially if you’re coming directly off of Priest’s take on the character, which was grittier and had more intricate storytelling. Hudlin’s run tonally feels similar to the older James Bond films, focusing on T’Challa from within his own head, as opposed to the use of a proxy. The politics aren’t absent in this volume, but they are more direct, unafraid of offending with their straightforwardness. United States officials refer to the Wakandans as “jungle bunnies” and the comic doesn’t flinch from the racial factors as to why the rest of the world continually underestimates Wakanda.

While John Romita Jr. and Salvador Larroca carry the front half of the book, the second half is largely handled by artist Scot Eaton. Eaton’s linework is incredibly detailed, and the thicker line weights he uses give inker Klaus Janson a lot to work with. The end result is a book that can change its look depending on the situation. Vampires in the Louisiana Bayou? Thick shadows, and rougher figures. A royal wedding? Beautiful detailing and smooth lines that make everything immaculate. Aiding in all of this is colorist Dean White who provides a visual consistency throughout the book. White uses warmer hues that give the book a heroic feeling, and uses deep blues and purples for sultry night scenes. In the final issue, Kaare Andrews makes a guest appearance for a supernatural sequence, and that transition between the styles of Eaton and Andrews really sells the other-worldliness.

The collection itself is printed well, and the dark blue of the volume serves as a distinctive visual indicator that this is different from the Priest run, so if you find yourself reaching for it on the shelf you can easily pick it out. For supplemental materials, the collection includes an article by Reginald Hudlin that was originally printed in the Who is the Black Panther? trade paperback, an article about the design of Storm’s wedding dress from The Bride as well as images of some of the cover sketches.

Is It Good?

More Sean Connery than Daniel Craig, Black Panther by Reginald Hudlin: The Complete Collection Vol. 1 is swaggering swashbuckling at its finest. Unapologetically black, it presents its titular hero and his kingdom of Wakanda at their highest point, blending afrofuturism, political intrigue, and adventure. There are some hiccups, and the lighter tone may not fit everyone’s tastes, but this is a solid collection that does its titular character proud.

Rating: 8.5 GREAT

Black Panther by Reginald Hudlin: The Complete Collection Vol. 1 is out now at comic shops and will be available at major retailers including Amazon on November 14th.

Comment

+ Permalink

‘Marshall’ depicts a fight for truth, justice and the American way

Chadwick Boseman stars as Thurgood Marshall in “Marshall.” (TNS)

By Lewis Beale | LA Times

Forget Luke Cage, Black Panther and Nick Fury. The real black superhero carries a briefcase filled with law books and a copy of the U.S. Constitution in his jacket pocket.

His name is Thurgood Marshall.

The strong-willed civil rights activist and Supreme Court justice is nothing if not heroic in the October release “Marshall.” With Chadwick Boseman in the title role, director Reginald Hudlin’s movie is the true story of an early case in Marshall’s career when, as the founder and only lawyer working for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, he defended a black chauffeur (played by Sterling K. Brown) accused of raping his white employer (Kate Hudson).

Josh Gad from left, Chadwick Boseman and Sterling K. Brown in a scene from “Marshall.” (Barry Wetcher / Open Road Films via AP)

Marshall “was fighting insurmountable odds” at the time, says Boseman, “dealing with limitations of space and time” as he bounced around the country taking on racially charged cases that were dangerous and seemed unwinnable. “The idea he could walk into those spaces in Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, go up against crowds of people who don’t want him to be there and try cases — and walk in with audacity — you could say that’s super.”

Adds Wil Haygood, author of “Showdown: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court Nomination that Changed History”: “He never took on cases that were easy. He took on cases that others said, ‘There is no way this is winnable,’ and he took on cases in enemy territory.”

Connecticut in 1941, where the legal action in “Marshall” takes place, was not the Deep South, but racism was still pervasive. The judge in the case (James Cromwell) refused to let Marshall speak in court, so he had to seek out white counsel to do his talking. The only person who would help him, reluctantly, was a young Jewish insurance defense lawyer named Sam Friedman (played by Josh Gad), who had no background in criminal law. This meant Marshall had to school him in the intricacies of trial procedure, and it also means that the film not only shows how Marshall trained lawyers to follow in his footsteps, but highlights the often close relationship between blacks and Jews in the early days of the civil rights struggle.

“The modern civil rights movement began not as a movement of large groups of people, but one man traveling around bringing lawsuits,” says Michael Koskoff, a Connecticut attorney who wrote the “Marshall” screenplay with his son Jacob. “Marshall believed they needed an army of lawyers, and if lawyers were not trained, the black community would not get their rights. Before there was a movement of civil disobedience, there was a movement harnessing the power of the law.”

Chadwick Boseman in a scene from “Marshall.” (Barry Wetcher / Open Road Films via AP)

Boseman notes that when it comes to the black-Jewish relationship, “there is a kinship in terms of oppression. The Jews know what it’s like to not be a part of the larger society. Even in this film there’s an inner circle in Bridgeport that Josh Gad’s character cannot get into, and that’s part of the story. Also in this film, it’s 1941, prior to the U.S. entering World War II, and that war was a clear case where white supremacy was a part of the war, and Josh Gad has to decide what he is going to do in terms of white supremacy at home.”

At the end of the film, Marshall is called away from Connecticut and sent to Mississippi to litigate yet another troubling case. He’s like a legal Superman, fighting for “truth, justice and the American way” — yet it’s not the America that is, but the one he wants it to be.

Or as Boseman puts it: “He made America live up to its dream, that all men are created equal. How do you do that? You challenge the laws. You are not accepting them; you are making them.”

Comment

+ Permalink