BLACK MONDAY

I just finished shooting two episodes of the new Showtime series BLACK MONDAY starring Don Cheadle. Look at this cool show with this amazing cast! And which scenes do you think are from my episode?

I just finished shooting two episodes of the new Showtime series BLACK MONDAY starring Don Cheadle. Look at this cool show with this amazing cast! And which scenes do you think are from my episode?

Black Cowboy and Black Panther! With my man Bill Bellamy ready for Halloween!

Comment + PermalinkBy Michael Cavna and David Betancourt

October 30

SINCE FEBRUARY, when Disney/Marvel’s smash “Black Panther” first captured not only audience attention but also the cultural zeitgeist, reporters have been asking the question: Which kids are permitted to don the superhero costume from the fictional African nation of Wakanda?

Or as Joshua David Stein wondered in a column at the time for Fatherly: “Should I allow my white son to dress as a black superhero?”

Jen Juneau wrote on People.com this month: “Parents of white children may want to think twice before purchasing a Black Panther Halloween costume this year.” And Steph Montgomery, writing this month for the online publication Romper, said: “I don’t think it’s appropriate for my white children to dress up as main characters T’Challa and Shuri, or the members of Dora Milaje — the badass women special forces of Wakanda.

“Because we’re a white family I know that ‘Black Panther’ does not exist for us,” she wrote. “Instead, I believe it exists for black kids who deserve to have heroes who look like them; something white people have long enjoyed and have taken for granted.”

As superhero diversity has increased in recent years, films such as “Black Panther” — not unlike such recent animated movies as “Coco” and “Moana” — can start conversations about issues of cultural appropriation, and who is allowed to dress as a certain character. Megyn Kelly’s comments defending the wearing of blackface on Halloween further stoked debate about how race is represented in costumes. But in interviews with The Washington Post, several creators who have helped shape the Black Panther character, along with other prominent authors who have written characters of color, are adamant: Any kid can dress as Black Panther.

“The idea that only black kids would wear Black Panther costumes is insane to me,” said Reg Hudlin, the Oscar-nominated filmmaker who has worked on Wakanda-set projects for both the page and screen, including the animated TV miniseries “Black Panther.” “Why would anyone say that?”

The top two films of the year, “Avengers: Infinity War” and “Black Panther” ($3.4 billion combined globally), both spotlight Wakanda — and Hudlin celebrates the omnipresence of its shiny-as-Vibranium costumes.

“I love that all kids want to be Black Panther or Shuri or the Dora Milaje,” Hudlin said of the royal-court characters, including T’Challa’s teen-genius sister Princess Shuri, created during Hudlin’s run on the comic. “These are the small steps that make the world a better place.”

Photo by ERIK S LESSER/EPA-EFE/REX Textile conservator Emma Schmitt keeps close watch over the recently acquired Black Panther costume at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington. The suit, worn by Chadwick Boseman in the 2018 film, is made of flexible 3-D printed materials and was donated to the museum by Marvel Studios and the Walt Disney Company.

When Hudlin was writing Black Panther comics, in fact, “one of the things I loved,” he recalled, was the diversity of its fandom.

“Every type of person showed up for a book signing: black, white, Asian, Latino — men and women, young and old,” he said. “It feels good to write something culturally specific that plugs into a universally relatable experience.”

Ruth E. Carter, the Oscar-nominated costume designer (“Malcolm X,” “Amistad”), created the beautifully intricate attire for Ryan Coogler’s “Black Panther,” drawing inspiration from not only the comics but also from real-world designs in Africa.

She says the point in creating such Afrofuturistic art is to build not barriers but, rather, cultural bridges — and so fans should embrace that the world of Black Panther is “taking its royal place in the vast Comic-Con and cosplayer universe.”

So why are people posing this question over T’Challa now, Carter says rhetorically.

“The only reason we’re asking that question now is because the Black Panther is a black man. And I think that’s what’s wrong with people — that’s what’s wrong with parents,” Carter said. “Because I see kids far and wide embracing the concept of a superhero. I believe they see him as someone who is majestic and powerful and doing good, and has a kingdom and a legacy and is pretty cool. I don’t think they see a black guy — I think they see the image of a superhero,” she added, and “it happens to be the Black Panther just as it happens to be Superman.”

Carter said it is the grown-ups who create an issue where children have none.

Parents, she said, “get so hung up on the wrong thing that kids aren’t even focused on — but they make the kids focus on it.”

And given the popularity of the Black Panther — a character created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in the 1960s — Marvel Comics “grabbed a whole [black] demographic that was not really represented and brought them in, and just opened the door to everyone. It didn’t mean that now it’s a segregated world — it means that it’s an inclusionary one,” said Carter, reflecting the film’s theme of whether Wakanda should stay isolated or connect with the rest of the globe.

“If we don’t embrace other cultures and let other ethnicities embrace ours,” Carter said, “then we’re hypocrites.”

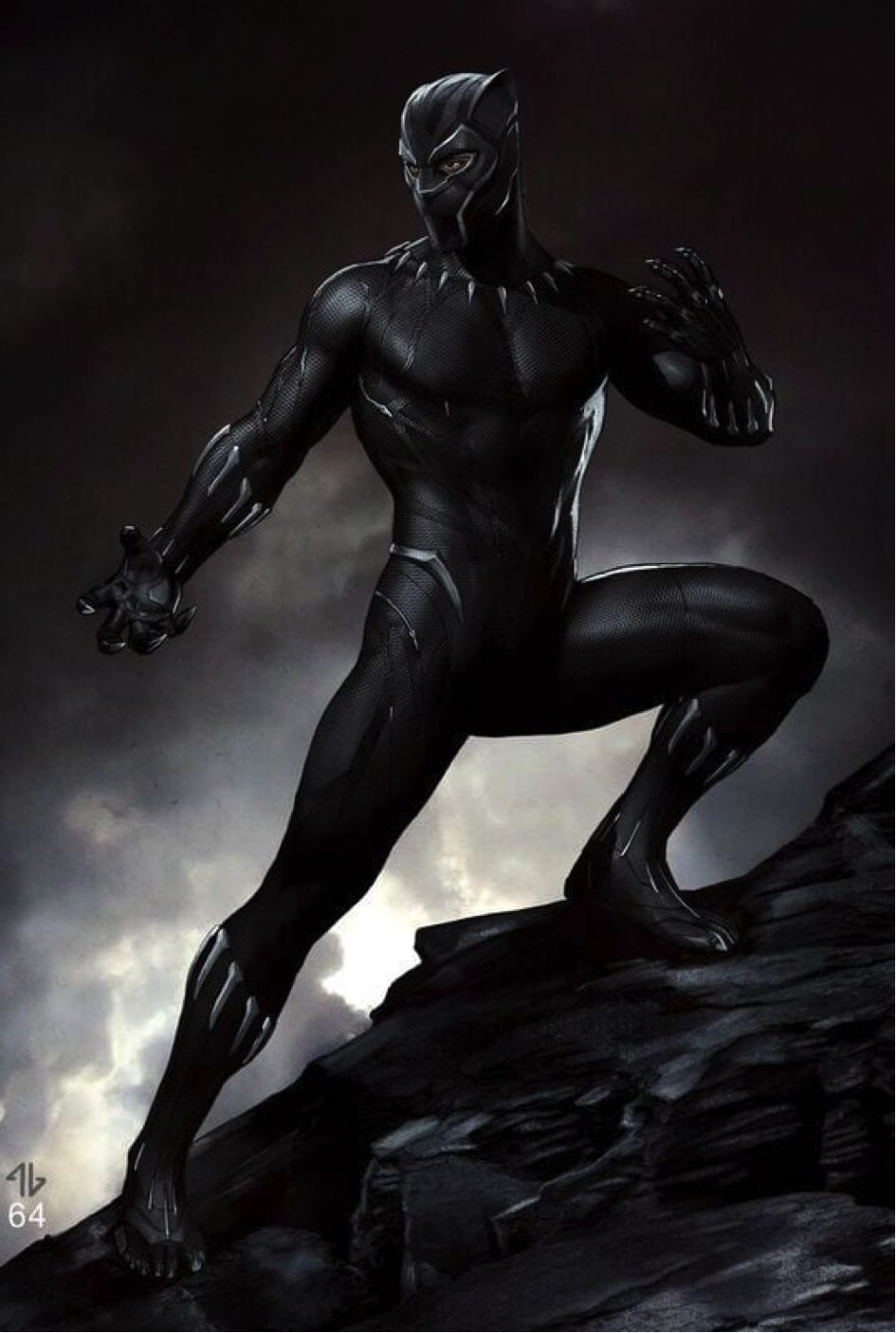

Disney/Marvel’s concept art for the costume design of “The Black Panther.” (Ryan Meinerding/VisDev with artist Adi Granov)

Shawn Martinbrough, a Washington-based illustrator (“Thief of Thieves”) who worked on the comic-book story arc “Black Panther: The Man Without Fear,” appreciates the creative interplay between the Kirby and Lee costumes of the ‘60s comics and Carter’s cinematic masterpieces — and believes that young cosplayers should feel free to wear any era’s look.

“I’m happy that kids across the spectrum feel so connected to the characters of Wakanda,” he said. “The more comfortable people are experiencing and embracing the beauty in other cultures makes them less likely to indulge in stereotypes.”

Gene Luen Yang, a Bay Area-based graphic novelist (“American Born Chinese,” “Boxers and Saints”) and past national ambassador for Young People’s Literature, loves to write about issues of identity — including through his recent co-creation of the DC Comics character Kong Kenan, a.k.a. the “Superman of China.” And he draws a distinction about costuming based on the intention of the wearer.

“It seems to me that when little kids dress up as fictional heroes for Halloween, they almost always do it from a place of admiration,” said Yang. His children “admire Superman or Black Panther or Rey from ‘Star Wars,’ so they want to try on their clothes for a day. Maybe deep down, they hope their heroes’ courage will bleed into them.

“Admiration obviously crosses lines of culture and gender — my kids admire plenty of people who do not look or live like them — so I think the same should be true for their Halloween costumes.”

When it comes to adults, however, sometimes “Halloween can be cover for certain individuals to express contempt for certain people and groups, all in the name of fun and irony,” said Yang, underscoring how the anonymity of a costume can provide cover for baser instincts.

“That said, I do believe in giving people the benefit of the doubt. I do not believe in policing the Halloween costumes of adults,” Yang said. “But I also believe in honest, blunt discussion when folks might have crossed the line.”

Keith Knight, creator of the strips “The K Chronicles” and “Knight Life,” appreciates a great costume, having been a Michael Jackson impersonator in his teen years. He said of the Black Panther issue, “Was that ever a question when dressing up as Batman or Superman? It’s a costume!”

“And, please, stop with the blackface,” he added. “You can dress as a black character without donning dark makeup.”

Lalo Alcaraz, the “La Cucaracha” comic-strip creator who was a cultural adviser on Disney/Pixar’s Oscar-winning “Coco,” believes that when it comes to costuming, the “Coco” characters now “belong to the world’s pop culture.”

“The success of ‘Coco,’ besides authenticity, was the universality of the film’s characters,” Alcaraz said. “Of course anybody can dress as the movie’s characters.”

Alcaraz feels similarly about Disney/Marvel’s fictional African world.

“If my kids wanted to dress up as Wakandans, I would be so happy,” he said. “Of course, they would never consider darkening their skin to portray these African-inspired comic-book and movie characters.

“If they did, I would go send them to live with Megyn Kelly as punishment.”

Comment + PermalinkNo Film School, Hawkins DuBois, October 12, 2017

Some of the most critical moments in American history have been realized courtesy of the country’s justice system and the courtroom. Brown v. Board of Education, Roe v. Wade, and the Scopes Trial were each landmark cases that dramatically shifted the tide of American life, helping lead to a national fascination with the courtroom that has extended to the cinema in the form of fictional masterpieces like To Kill A Mockingbird and A Few Good Men. On-screen, these monumental cases have drawn a great deal of attention, with movies suitably lending their focus to the dialogue. While questioning, cross-examining, and objecting remains at the forefront of the story in Marshall, DP Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC, also makes sure to bring a visual life to the courtroom drama.

Marshall tells the story of none other than a young Thurgood Marshall, one of America’s genuine heroes and the first African American Supreme Court Justice, as he embarks on a court case that will help keep the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People afloat. Prevented from speaking in the local Connecticut court, Marshall (Chadwick Boseman) recruits Sam Friedman (Josh Gad) to help in defense of Joseph Spell (Sterling K. Brown), a black man who has been accused of rape by his employer, Eleanor Strubing (Kate Hudson).

No Film School recently sat down to speak with Sigel about his work on Marshall, discussing his methods for keeping the courtroom engaging, crafting innovative lighting strategies to fit your situation, and adjusting color palettes based on character perspective.

No Film School: At the film’s Los Angeles premiere, director Reginald Hudlin described you as his right-hand man on the movie. How intimate was your relationship with him on-set?

Newton Thomas Sigel: Reggie was a pure joy to work with. He was very clear about the kind of movie he wanted to make all through prep, and how he planned to do it for such a limited budget. Once photography started, we would meet every Sunday and go through the week’s work, talking about shot-listings and discussing what his intent was for each scene. It’s what made shooting on such a tight schedule possible—not only the planning, but his enthusiasm for what we were accomplishing on set. It was very infectious.

NFS: How did you meet Reggie? When did you first get involved with the project?

Sigel: I’ve known Reggie for more than twenty years, and I’ve always loved his upbeat spirit. He’s made many successful comedies, but this is the first film he’s done something that was more in my dramatic wheelhouse.

Chadwick Boseman in “Marshall” (dir. Reginald Hudlin). Shot by Newton Thomas Sigel. Credit: Open Road Films

NFS: What was it about this story that attracted you to do the movie? What things did you see in the script that you wanted to lift off of the page and put on the screen?

Sigel: Who would not want to do a movie about Thurgood Marshall? He is such a towering figure in American history, not to mention a wonderfully colorful personality. This particular story was great because of the twists and ambiguities involved. Brown versus The Board Of Education was obviously an extraordinarily important case for Marshall and the American people, but the story we tell in Marshall is not quite as clear, and the right and wrongs prove to be very complex. That’s what made for great drama that I found attractive.

NFS: You’re capturing a very distinctive period with the 1940s, and the movie opens with a sort of grainy film stock type of look. I’m guessing shooting on film was never an option with the budget, so as the DP, what kind of tricks did you employ to put audiences in that period?

Sigel: As with most period films, the look begins with production design and costume. There’s nothing like a car, a haircut or a costume to send you back in time. Starting there, I looked for a color palette that brought out our best. A big challenge was that, being a courtroom drama, I mostly had guys in suits—not much color there. So we created an LUT that gave the film a dated look—notably adding a slight hint of blue into the shadows.

NFS: A significant portion of this film takes place in a courtroom, and I’ve heard that you guys got access to a real location, but that there were some complications. How do you approach lighting a courtroom in general, and the specifics of dealing with your courtroom, in particular?

Sigel: The courtroom we had was a blessing and a curse. How often do you get a vacant courtroom, period-perfect, for weeks at a time? But…it was several stories up, almost 80 feet in the air, with huge windows, and 90% of my work was daytime. I was fortunate enough to be able to get two lifts with 18Ks that did almost all of the heavy lifting, which meant that very little light was used inside the courtroom. Each of the lifts had a truss with two LRX’s, which are HMI lights that can be panned and tilted remotely, so there was no need for an electrician to be up in the bucket.

One of the other issues with the location was a nasty white wall, but Production Designer Richard Hoover blessed me with a beautiful mural that covered the bulk of it. Although the trial mostly took place during the day, we also wanted to communicate a passage of time and an arc to the look of the trial. We created a variety of looks from strong Venetian-blind contrast, to soft diffused daylight.

We also had a night scene where the windows had to be blacked out. For that, I used the overhead chandeliers and fairly flat, warm light.

NFS: There are a couple of cool crane shots in the courtroom too. What was your strategy for employing a crane on a location like that?

Sigel: There is actually very little crane work. I think we had it for one or two days. My favorite use of the crane was the way we introduced Kate Hudson’s character, Eleanor Strubing. It’s a huge moment in our story when the accuser enters the courtroom to testify. The camera starts on the ground, looking up at the doors as she comes through with her husband. We lift up and wrap around her as she makes her way to the stand and we go wide, wide, wide to show the audience the whole room. The shot makes a statement about her importance in the trial, and when you see how we wrap around the couple, it tells us something about her relationship with her husband.

NFS: I’ve heard about a couple of tricks you helped to create on-set such as artificially manufacturing the feel of a train rolling into the station. How did you come up with and execute that idea?

Sigel: We had a scene where Marshall was threatened while he is waiting for a train. It’s a night scene, and we found a great old small-town station. But… the tracks were not safe for the only working period train in the area. We were able to locate a manual trolley that fit on the tracks. We put a “headlight” on it, connected it to a dimmer, wrapped it in black, added smoke to the trolley, and the grips pushed it along the track. I kept the tracks black, so basically, we were backlighting smoke—but it worked.

NFS: Looking at the flashbacks/memory sequences, how did you settle on their aesthetic, and did you do anything to shoot those scenes differently based on whose perspective the story was being told from?

Sigel: The flashbacks aren’t black and white, but they are extremely desaturated with a very narrow palette. We tell the story of the ‘crime’ from both the point of view of the accuser and the accused. The color palette was kept to a soft blue, and a faded yellow. The balance between the two changed when we went from Eleanor’s story to Joseph’s.

NFS: Civil rights is obviously a major theme in this story and the treatment of African Americans specifically. As the DP, how did you approach shooting the black actors in this film, and how do you deal with issues of lighting a white and a black actor in the same shot?

Sigel: Darker skin tones always present a different challenge than paler flesh-tones. If your intent is to bring your characters away from the background, you can put a light-skinned actor against a dark wall, or have them in dark wardrobe and the job is half done. When you have a very dark skin tone, you need to look for other solutions. Reflective qualities to the skin or harder edges to create separation. Digital has made this much simpler because of its ability to see into shadows. And after all, you’re not trying to make Chadwick Boseman look like Josh Gad!

Chadwick Boseman and Josh Gad in “Marshall” (dir. Reginald Hudlin). Shot by Newton Thomas Sigel Credit: Open Road Films

NFS: A lot of DPs talk about lighting women differently than men too. Is that something you do?

Sigel: I don’t light women different than men, but I do light for character. Is the actor meant to be beautiful, or haggard? Older or younger? Hung-over, or glowing? The quality of the light and the way I treat human “imperfections” is always in the service of the story.

NFS: What camera did you shoot on? What lenses did you use primarily?

Sigel: Arri & CSC were amazing. They managed to get us an Alexa 65 package with Vintage and Prime 65 lenses. There was no way we should have been able to afford it, but we found a way. The gear was flawless and their service terrific. I know that sounds like a commercial, but it’s true.

NFS: As someone who has done a lot of action-heavy work recently in your films and television, how do you approach the brief action scenes in a more dramatically-focused film such as this one?

Sigel: The action in Marshall is more psychological than big set pieces. We had no time to shoot them—only a matter of hours—so they were really more about the ugliness of hatred and bigotry than about being fancy shots.

NFS: What was your most challenging aspect of the shoot?

Sigel: I think the hardest thing was having over forty pages of script in the courtroom. To keep the audience engaged, we created a different character for each scene of the trial. This helped create an arc and contributed to the unease of our story. We begin somewhat formal and classic in composition and blocking. By the end, we are hand-held and almost frenetic.

Comment + Permalink